- column

- CAMPUS TO CLIENTS

LITCs: Not just for law schools

Related

CPA firm M&A tax issues

Return preparer reliance on third-party tax advice

IRS broadens Tax Pro Account for accounting firms and others

Editor: Annette Nellen, Esq., CPA, CGMA

Numerous studies document the need for accounting programs to adequately prepare students for work in the real world (e.g., Walsh, “Closing The Gap Between Accounting Education and the Workplace,” 54-2 The Tax Adviser 46 (February 2023)). Low Income Taxpayer Clinics (LITCs) are one way to address this issue. While rare, LITCs located in business schools (rather than at law schools) provide a valuable experiential learning opportunity for students, much-needed tax assistance to low-income taxpayers in the local community, a way for faculty members to apply their accounting and legal skills to solve problems for actual clients while mentoring students, and additional federal and private funding sources for colleges.

What are LITCs?

LITCs represent low-income taxpayers involved in controversies with the IRS. They also provide education on the rights and responsibilities of U.S. taxpayers and outreach services to individuals who speak English as a second language. LITCs began in law schools during the 1970s as part of a broader social movement to provide practical skills to law students while expanding legal-aid services to low-income individuals in the area of tax law (Fogg, “Taxation With Representation: The Creation and Development of Low Income Taxpayer Clinics,” 67-1 The Tax Lawyer 4 (Fall 2013)). The clinics then spread to legal-services organizations; eventually, a few clinics opened in business schools. These programs’ positive impact on society is clear. According to the Taxpayer Advocate Service (TAS) webpage, during 2022 alone, LITCs “represented 20,358 taxpayers, educated 143,260 taxpayers and service providers, helped secure $6.7 million in refunds and decrease[d] or correct[ed] $62 million in tax liabilities.”

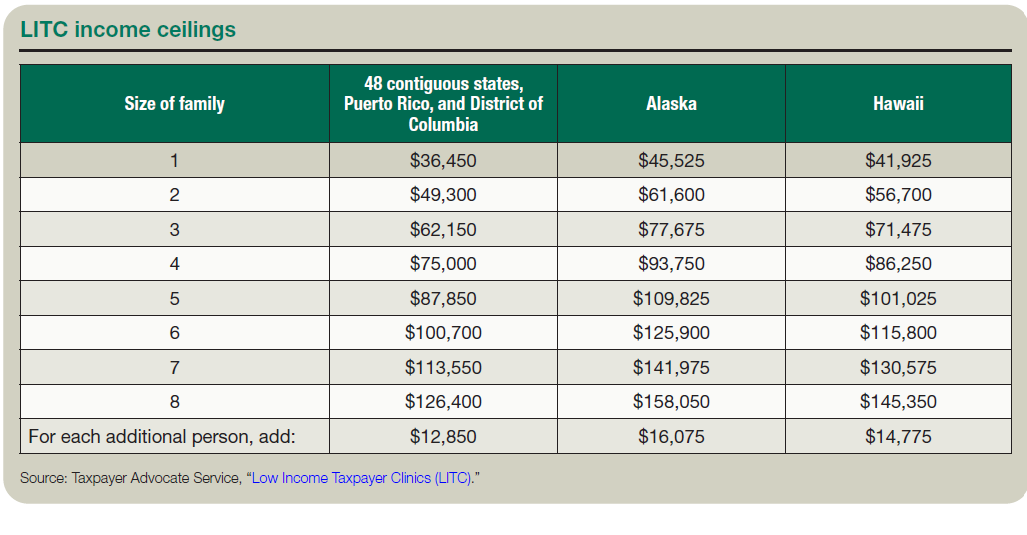

Depending on a particular clinic’s parameters, qualifying individuals receive all services at no charge or at a low cost. A qualifying individual is one whose income does not exceed 250% of the federal poverty guidelines (as defined by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services) and who has a controversy with the IRS that does not exceed $50,000 per tax year. LITCs have some discretion to deviate from these standards as long as clients with such deviations do not exceed 10% of all clients in a given year. The chart “LITC Income Ceilings,” below, shows the 2023 incomes that qualify for representation.

What types of cases do LITCs handle?

Unlike Volunteer Income Tax Assistance (VITA) programs, which are frequently housed in business schools and focus on tax compliance, LITCs focus on resolving tax controversies. Clients typically come to an LITC after receiving correspondence from the IRS regarding an audit, a notice of deficiency, or, if the case is further along, the filing of a tax levy or lien. When a potential client seeks LITC help, the clinic’s first step is to determine the client’s eligibility for services. If the client is eligible, a clinic representative evaluates his or her case to determine whether the client owes the liability the IRS is asserting. If not, the clinic determines how it can help the client prove their case. It does so by assisting the client in gathering the necessary documentation and preparing and submitting the appropriate response, whether it be a reply to an audit notice, a request for a Collection Due Process hearing, or a petition in Tax Court. Although each case is unique and must be fully evaluated, controversy cases a clinic might typically handle include the following:

- Representation relating to a dispute involving an IRS account, collection, examination, or Appeals Office matter or a federal tax matter in federal courts (including the Tax Court);

- Assistance to a victim of identity theft on a federal tax matter;

- Preparation of an amended return if necessary to resolve a controversy for a client;

- Representation in innocent- or injured-spouse cases;

- Representation in a state or local tax controversy when the clinic is representing that taxpayer in a federal tax controversy;

- Proving entitlement to certain tax credits (such as the earned income tax credit);

- Proving dependents; and

- Helping noncitizens obtain individual taxpayer identification numbers.

Once the LITC determines the appropriate category and path to resolution, students, under the supervision of legal or accounting faculty, devise a plan to resolve the dispute. If the clinic determines that the client does owe the liability but is unable to pay it due to economic hardship, the clinic may still be able to assist the client by helping them work out a settlement with the IRS through the offer-in-compromise process, by assisting the client in obtaining an installment agreement, or by having the client placed in a noncollectible status. Each of these types of assistance requires the collection and analysis of detailed financial and other relevant information and the preparation of multiple tax forms.

Due to the nature of an LITC’s work, most clients are experiencing economic hardship. Many also suffer from mental or physical health issues, are unhoused, or have other nonfinancial challenges. Thus, while LITC work involves the use of accounting and legal skills to help resolve tax controversies, working with LITC clientele is also a good way for students to gain valuable people skills and a fuller understanding of the struggles faced by a diverse group of people.

Benefits to business colleges with LITCs

Currently, there are 132 LITCs in the United States, with the majority located within law schools or as part of legal-aid programs. In fact, only four currently operating clinics are located within business schools (IRS Publication 4134, Low Income Taxpayer Clinic List). LITCs located within business schools provide a unique opportunity for accounting students and professors to apply their skills and knowledge in a real-world setting typically available only to law students. This application of skills exceeds what students and professors can experience in the classroom. In most clinics, students participate in all parts of representation, from doing client intake, strategizing how best to resolve disputes, and performing legal and tax research to gathering financial and tax information and preparing and writing official documents (such as affidavits and memorandums).

In addition, students might have the opportunity to help resolve cases pending before the Tax Court and observe trials. For example, many LITCs have agreements with the Tax Court to participate in its Calendar Call program. Through this program, clinic representatives attend calendar call sessions and provide on-the-spot assistance to unrepresented taxpayers scheduled for trial. Although accounting students — unlike law students — may not make court appearances, they are able to assist any clinic lawyers who attend, much as paralegals would. This assistance includes meeting with litigants and IRS attorneys, attending settlement conferences, and observing trials. Sometimes the Tax Court judge assigned to the calendar will carve out time to meet with the students and answer any questions they have; the judge might even invite them into chambers for a behind-the-scenes look.

How do you open an LITC?

LITCs are partially funded by grants awarded annually through TAS. Grant proposals are usually due at the end of June for the following calendar year. Sec. 7526(c)(5) requires that any grant TAS awards (which can be up to $200,000 annually) be matched dollar for dollar by an outside, nonfederal source. Matching amounts can come from the university; from private donors, such as alumni or community members; and as in-kind donations of supplies or time, such as volunteer work donated by local CPAs, lawyers, or faculty members. While the successful outcomes of the work that clinics do are a source of compelling stories to share with potential donors, they also represent a way to leverage dollars already being spent on course instruction to bring in additional funding. Detailed information about the grant application process can be found at the TAS website. It is crucial that LITC applicants and operators work closely with their respective universities’ support structure to ensure that university policies and procedures are properly followed.

Once funding has been acquired, LITCs are free to organize and staff the clinic as they see fit. However, each clinic needs a director, a qualified tax expert, and a qualified business expert to handle day-to-day operations. Depending on the size of the clinic, each of these positions can be filled by a different person, or one person can wear multiple hats. TAS grants come with reporting and tracking obligations, so clinics must maintain accurate records and file interim and annual reports that detail all monies spent and work performed. Grantees must also attend a conference that TAS hosts every December.

When an LITC resides in an academic setting, its associated business or law school can offer the clinic as a class that combines accounting and legal training with actual client work. One format is to have the first few weeks of the class consist of intensive training that includes an in-depth orientation in clinic operations, confidentiality requirements, ethical issues, tax and legal research methods, and information related to typical casework. Once the training portion is completed, students are assigned clients and begin regular shifts in the clinic to complete their client work. Other formats could combine ongoing instruction throughout the academic term with client work. Graduate students and others who have completed the program can be hired to serve as team leaders and mentor current students.

Gaining experience while helping taxpayers overcome challenges

LITCs furnish accounting students with an excellent way to apply the skills they learn in the classroom and to gain practical, hands-on experience while helping real people overcome difficult situations. Faculty members who teach the LITC course or volunteer as part of a clinic’s pro bono panel can also use their skills to provide a valuable public service while mentoring students outside the classroom. In addition, tax professionals from outside the university are welcome to volunteer at an LITC. Volunteering can be a way for these professionals to serve taxpayers in need while also helping students gain practical experience in serving clients. Thus, LITCs in business schools provide practical training, additional funding, and a valuable public service.

Contributors

Elisabeth “Lisa” Sperow, J.D., is the executive director of the Cal Poly Low Income Taxpayer Clinic within the Orfalea College of Business at California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo, Calif. Annette Nellen, Esq., CPA, CGMA, is a professor in the Department of Accounting and Finance at San José State University in San José, Calif., and is a past chair of the AICPA Tax Executive Committee. For more information about this column, contact thetaxadviser@aicpa.org.