- tax clinic

- credits against tax

The true cost of ERC noncompliance

Related

Businesses urge Treasury to destroy BOI data and finalize exemption

IRS generally eliminates 5% safe harbor for determining beginning of construction for wind and solar projects

Deducting corporate charitable contributions

Editor: Mark Heroux, J.D.

The adage “if something sounds too good to be true, it probably is” can be difficult for employers to adhere to when media, including peer networks, continuously advertise that their business may qualify for hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of dollars’ worth of employee retention credit (ERC) payroll tax refunds. They might ask, “Surely the ERC is legitimate if everyone is claiming it?”

Well, the ERC is very real and can be lucrative for employers that meet the eligibility criteria. However, the eligibility requirements are strict, despite dubious assertions that all employers qualify, propelled by a manufactured fear of missing out. In fact, abusive ERC claims are so pervasive that the IRS reiterated the too-good-to-be-true adage in an October 2022 warning to taxpayers, which the Service then followed with multiple additional warnings, including by headlining its annual “Dirty Dozen” abusive tax scheme list for 2023 with promoters pushing the ERC (“ERC mills”) (see also Waggoner, “A Pandemic- Era Tax Break That Remains Rife With Abuse — the ERC, The Tax Adviser, June 1, 2023).

Although the ERC, one of Congress’s responses to the effects on businesses of the COVID-19 pandemic, was available only in 2020 and the first three quarters of 2021 (also the fourth quarter of 2021 for “recovery startup businesses”), employers may still file claims for that period. Generally, the ERC provided eligible employers a refundable credit against applicable employment taxes equal to 50% for 2020 or 70% for 2021 of up to $10,000 of qualified wages paid each employee per applicable calendar quarter (Secs. 3134(a) and (b)).

Some employers understand that claiming the ERC based on an aggressive position is a gamble but underestimate the stakes involved. They mistakenly believe one simply must repay the credit if their position is not sustained upon IRS audit. This perception of minimal risk, paired with the promise of a windfall, has clouded the judgment of many. Aggressively claiming the ERC is a high-risk gamble, and, for the well-informed, the juice may not be worth the squeeze.

This item highlights the risk, financial and otherwise, of aggressively pursuing the credit by discussing the costs relating to claiming it, showing that the net cash benefit of even a properly approved claim is generally significantly less than the credit claimed and that losing an IRS audit and repaying the credit can cost employers far more than just the ERC amount.

The two primary categories of costs discussed are those related to claiming the ERC and costs potentially incurred if the employer is audited by the IRS and required to repay the credit. They are:

Consultancy fees and other costs to calculate the ERC: Whether working with an ERC mill or tax adviser or performing the analysis in-house, employers incur a cost to determine eligibility for and the amount of credits to claim. Due to the ERC’s often overwhelming complexity and ERC mills’ predatory marketing, many employers chose to engage a mill to assist in this process. These mills generally promote positions that are aggressive, if not outright contradictory to IRS guidance and often charge a percentage fee of the total ERC amount claimed, typically 10% to 30%.

Risk analysis: If a percentage fee was paid, what is the likelihood it can be recovered if the ERC must be repaid because of an IRS audit? Employers should review the terms of their contract and keep in mind that even if it includes a fee refundability provision, the provision may be extremely difficult to enforce.

Increased tax: The law and guidance make clear that employers are required to reduce their compensation expense by the amount of the ERC claimed in the tax year the wages are paid or accrued (“rules similar to the rules of … [Sec.] 280C(a) … shall apply” (Section 2301 of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, P.L. 16-136)). For flowthrough entities’ equity holders subject to the highest marginal rates, if the entity failed to reduce its deduction, an additional federal tax of 37% of the ERC claimed could apply. For most credit claimants, the deduction must be reduced on an amended income tax return or via an administrative adjustment request (AAR).

Risk analysis: The ERC statute of limitation on assessment is based on the filing date of the return that includes the calendar quarter for which the credit was determined (or the date it was treated as filed under Sec. 6501(b)(2)) (Sec. 3134(l)). For the third (and, for recovery startup businesses, fourth) quarter of 2021, the ERC statute of limitation is five years.

As such, it is possible that an IRS audit that results in the taxpayer’s repaying the ERC could conclude outside the statute of limitation period to amend the income tax return (generally, three years). If the limitation period on the income tax return closes prior to the ERC audit adjustment and repayment, the compensation expense deduction could be permanently lost, resulting in a phantom income tax. It should be further noted that White House budget proposals include an ERC statute of limitation extension for all calendar quarters in which the ERC was available (General Explanations of the Administration’s Fiscal Year 2024 Revenue Proposals (Greenbook), p. 179). That said, these are merely proposals, and it is unclear whether such provisions will pass as law.

Administrative compliance fees: Among the costs that decrease the net benefit of the ERC are administrative compliance fees. First, if the ERC was not claimed on an original payroll tax return (Form 941, Employer’s Quarterly Federal Tax Return), Forms 941-X, Adjusted Employer’s Quarterly Federal Tax Return or Claim for Refund, must be filed for each quarter for which the ERC is claimed. Additionally, the compensation expense adjustment, as discussed above, must be reported on the income tax return for the tax year that includes the quarter for which the ERC was claimed.

For employers with an ERC claimed in both 2020 and 2021, both years’ income tax returns will need to be amended if the compensation adjustment was not reflected on the originally filed returns. For flowthrough entities, this also requires amended Schedules K-1, Partner’s [or Shareholder’s] Share of Income Deductions, Credits, etc., and amended Forms 1040, U.S. Individual Income Tax Return, by each individual shareholder or partner. Entities with multiple owners or partners may find this burdensome and expensive, perhaps even more so if AARs are involved (briefly discussed below).

IRS audit defense: Besides the possible cost of having to repay credits claimed, taxpayers typically prefer to engage their tax return preparer or legal counsel to defend them in an IRS audit. The associated fees can range widely depending on the firm engaged and the taxpayer’s facts and circumstances, but for purposes of this discussion, a five-figure fee should be anticipated. Some ERC consultants’ contracts include audit defense, but much like a contingency fee clawback provision, audit defense may be difficult to enforce.

Penalties: Multiple penalties could apply to the ERC. The Sec. 6651(a)(2) failure-to-pay penalty may be assessed if it is shown that the failure is due to willful neglect. The penalty is equal to 0.5% of the tax for each month (or portion of a month) that it is unpaid, not to exceed 25%. Additionally, the IRS could impose a penalty for an erroneous claim for refund or credit equal to 20% of the refund or credit exceeding any allowable amount (Sec. 6676).

Interest: Interest on erroneous refunds is generally assessed from the date of payment of the refund. Further, interest is also assessed on any penalties as discussed above. Critically, such interest compounds daily. IRS audits of ERC claims have begun only relatively recently, so it may be common for more than a year to pass between a taxpayer’s receiving the ERC refund and having to pay it back upon audit. This would result in substantial interest being due with the repaid claim.

Hypothetical case study

Example: An employer claimed an ERC of $1 million for the third quarter of 2021 and received a refund on April 1, 2022. The employer did not meet the suspension or significant-decline-in- gross-receipts test for this quarter (see Sec. 3134(c)(2)(A)(ii) and Notice 2021-20) but used an ERC mill that provided the employer with a memorandum stating that the employer is eligible for the credit due to industrywide supply chain disruptions, as well as under guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration.

As discussed in the authors’ previous Tax Clinic item (Tenney and Wronsky, “Employee Retention Credit: Navigating the Suspension Test,” 53-10 The Tax Adviser 7 (October 2022)), these are ill-advised taxpayers in pursuit of eligibility. The memo in the example above listed use of face coverings, installation of acrylic sheeting dividers, and other increased costs as evidence of a more-than-nominal effect on business operations but otherwise provided no detailed descriptions or a showing of a more-than-nominal effect pursuant to the guidance in Notice 2021-20.

An eligible employer properly meets the suspension test when its trade or business is fully or partially suspended due to orders from an appropriate governmental authority limiting commerce or certain other activities due to COVID-19 (the suspension test). A partial suspension of a business designated “essential” under a governmental order can occur if more than a nominal portion of its business is suspended by the order.

Notice 2021-20 gives as an example of a more-than-nominal effect resulting in a partial suspension a requirement that a restaurant’s indoor dining tables be spaced at least six feet apart (Q&A 17, Example 2). However, it also states that modifications altering customer behavior, such as requiring face masks or one-way store aisles, do not have more than a nominal effect (Q&A 18). Costs of required modifications do not themselves result in a partial suspension.

Alternatively, an employer may be eligible for the ERC by having gross receipts less than 50% (2020) or 80% or less (2021) of its gross receipts in the same calendar quarter in 2019 (the significant-decline-in-gross-receipts test) (Sec. 3134(c)(2)).

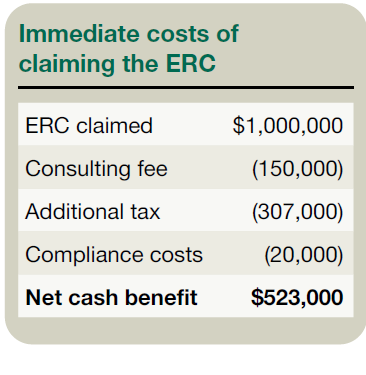

After determining that the employer in the example above is eligible for a $1 million ERC, the ERC consulting firm charged a 15% fee based on the total ERC claimed, or $150,000, payable immediately. The following table “Immediate Costs of Claiming the ERC” analyzes the net benefit.

The ERC’s real economic benefit is just over half of the original ERC claim.

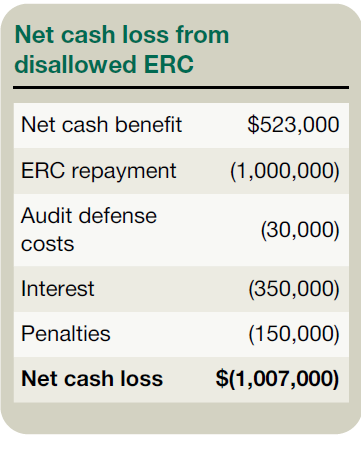

Further assume that shortly before the statute of limitation expires for the ERC claim in 2027 and after the expiration of the statute of limitation for the 2021 income tax returns, the IRS audits the employer’s claim. The employer engages tax counsel to assist in its defense, but ultimately, its ERC claim is denied on April 1, 2027. The employer must repay the $1 million, including interest and penalties. As the statute of limitation for its income tax return has expired, the employer cannot amend it to reclaim the compensation expense and recover the $307,000 in tax. The employer also encounters difficulty in recovering the $150,000 consulting fee.

The table “Net Cash Loss From Disallowed ERC,” below, shows the potential net negative amount resulting from the IRS audit and ERC repayment in a worst-case scenario. The gamble is a potential loss of $1,007,000 for a benefit of $523,000. For many employers, it’s not worth the risk.

Granted, this is a hypothetical, worst-case scenario. Employers with legitimate support for eligibility will, hopefully, prevail in an IRS audit. Others may have avoided consultancy fees or high credit calculation costs or had losses offsetting the additional tax or audits concluding before the income tax returns’ statutes of limitation expire. Perhaps an IRS auditor will forgo penalty assessments.

For many, the true costs upon repayment will largely be fees for compliance and audit defense and interest. But for employers claiming large amounts of ERC based on dubious advice from ERC consultancy firms, this scenario is not unrealistic, and potential exposure should be carefully considered. The IRS appears to be targeting employers that used the services of “promoters,” and those employers likely carry the largest amount of potential exposure.

Other impacts

Exposure extends beyond compliance; for example, for a taxpayer who claimed a significant ERC, it will all but assuredly be an item of inquiry in due diligence should the taxpayer enter into an agreement to sell its business (see Palko, “M&A Transactions: The Value of Sell-Side Tax Diligence,” 54-8 The Tax Adviser 18 (August 2023)). A failure to satisfactorily support the claim will likely reduce the purchase price. Additionally, the risk of taking aggressive ERC positions has implications for an employer’s financial statements, which should be discussed with the employer’s assurance providers.

As discussed above, flowthrough entities amending income tax returns to reduce the deduction for wages on which the ERC was claimed creates a significant compliance burden. The reduction of the deduction can be even more onerous in the case of a partnership subject to the centralized partnership audit regime, which must execute the reduction via an AAR rather than an amended return.

A detailed discussion of the centralized audit regime is beyond the scope of this item, but the partnership can either pay the “imputed underpayment” on the reduced deduction itself (which could, in fact, reduce the compliance burden) or “push out” the responsibility to the partners in the partnership as of when the wages were paid or accrued. The drawbacks of the partnership’s paying the tax include potential liquidity issues and the current partners being burdened by the tax. However, pushing out the imputed underpayment can be an administrative nightmare for large partnerships, especially those with other partnerships as partners.

Seek all available resources

The ERC rules are complex, and guidance, while limited, includes substantial warnings for employers that aggressively interpret the rules or fail to conduct appropriate due diligence before reporting the credit. The AICPA has many resources to help members understand the rules (see Employee Retention Credit Guidance and Resources). The authors recommend that employers use all available resources when it comes to the ERC.

Editor Notes

Mark Heroux, J.D., is a tax principal in the Tax Advocacy and Controversy Services practice at Baker Tilly US, LLP in Chicago.

For additional information about these items, contact Heroux at mark.heroux@bakertilly.com.

Contributors are members of or associated with Baker Tilley US, LLP.