- column

- CASE STUDY

The double-tax consequences of an S corporation subject to BIG tax

Related

Buy/sell agreements for S corporations

PTEs need more notice of changes, more time to respond, AICPA says

Late election relief in recent IRS letter rulings

This case study illustrates the tax consequences and the shareholders’ cash flow resulting from the liquidation of their S corporation when the S corporation is subject to the built-in gains (BIG) tax. For background on the BIG tax, see Markwood, ed., “The Built-In Gains Tax,” 51 The Tax Adviser 822 (December 2020) . For other S corporation liquidations generally, see Markwood, ed., “Liquidating an S Corporation That Is Not Subject to the BIG Tax,” 50 The Tax Adviser 864 (December 2019).

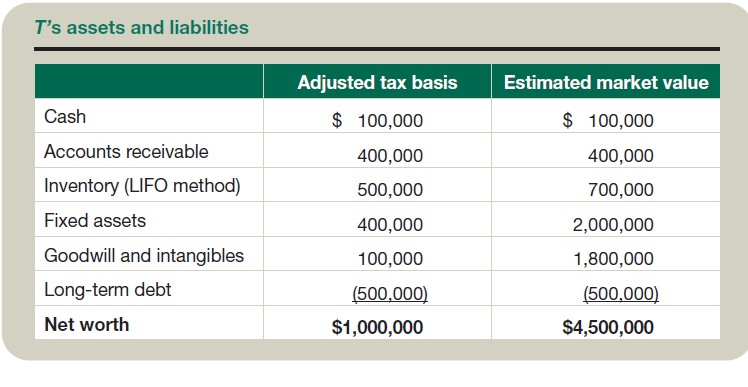

Example. Liquidating an S corporation that is subject to the BIG tax: T Inc., a C corporation, elected S status effective on Jan. 1, three years ago. T has 15 shareholders, all of whom are unrelated individuals. As of the beginning of its current tax year, T has assets and liabilities as shown in the table “T’s Assets and Liabilities,” below.

The shareholders each invested $50,000 when the corporation was formed and as a group have a total tax basis of $750,000 in their stock. (If T has always been an S corporation, the shareholders’ total tax bases in their stock would normally equal the corporation’s adjusted tax basis in its assets.)

Assume in this example that each of the 15 shareholders is considered a high-income taxpayer for purposes of Secs. 1(h) and 1411 and that any ordinary income from the transaction will be taxed at a 37% marginal rate (the highest individual tax rate). Therefore, the shareholders are subject to the 20% maximum tax rate for qualifying dividends and capital gains, and these amounts may be subject to the 3.8% net investment income tax (whether the surtax applies depends on each shareholder’s unique tax circumstances).

The corporation has received an unexpected offer to sell its inventory for $700,000, its fixed assets for $2.5 million, and the intangibles for $1.8 million, for a total sales price of $5 million. If the corporation accepts the offer, it would retain its cash and collect its receivables, retire its debt, and liquidate shortly after the sale. The corporation’s net income from operations from Jan. 1 to the date of the sale is projected to be $500,000, and the depreciation recapture from the proposed sale would be $800,000.

T is subject to the BIG tax because it was a C corporation before converting to S status and is disposing of assets at a gain within the five-year period following conversion to S status. The extra layer of BIG tax incurred by the corporation generates significant tax to the shareholders, compared to an identical corporation not subject to the BIG tax.

Corporate-level BIG

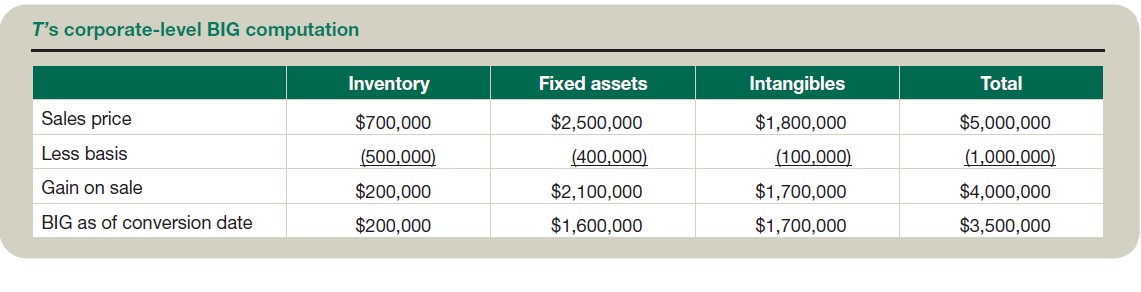

The corporate-level BIG in this example is computed as shown in the table “T’s Corporate-Level BIG Computation,” below.

The maximum potential BIG subject to tax is limited to the net appreciation of the corporate assets as of the corporation’s conversion to S status. T has the burden of proof to establish that its BIG on its assets at the time of the S election was $3.5 million rather than the $4 million actual gain on the sale (Sec. 1374(d)(3)).

Inventory

The value of an S corporation’s inventory on the first day of the recognition period generally is determined by reference to a hypothetical sale of the entire business of the S corporation to a buyer that expects to continue operating the business. The buyer and seller are presumed not to be under any compulsion to buy or sell and to have reasonable knowledge of all relevant facts. The regulations expect that the value so determined will generally be less than the inventory’s anticipated retail price but greater than its replacement cost (Regs. Sec. 1.1374-7(a)).

Continuing with the facts in the above example, it is assumed that as of the date of the S election the corporation’s adjusted basis in its LIFO inventory (after the basis increase, if any, for the Sec. 1363(d) LIFO reserve recapture) was $500,000, and the BIG value of the inventory was $700,000, resulting in a $200,000 BIG (see also Regs. Sec. 1.1363-2(a)(1) and Rev. Proc. 94-61 for more on LIFO recapture).

Assuming the BIG taxable income limitation does not apply (discussed below), the S corporation will be liable for the BIG tax attributable to the inventory as the inventory is sold. The BIG tax applies whether the inventory is sold in bulk or is sold to customers in the normal course of business. Since the entire inventory (including the pre–S election inventory layer) will be sold in bulk as part of the sale and liquidation of the company, the entire $200,000 BIG attributable to the inventory will be recognized.

BIG tax

The $3.5 million of BIG is composed of $1 million of ordinary income items (depreciation recapture of $800,000 plus inventory profit of $200,000) and $2.5 million of capital gain items ($1.6 million gain on fixed asset less $800,000 recapture, plus $1.7 million gain on intangibles).

The BIG tax to be paid by T is computed as shown in the table “T’s BIG Tax Computation,” below. The S corporation net passthrough income from T is shown in the table “T’s Net Passthrough Income,” also below.

The gain on sale of assets of $4 million that passes through to the shareholders is calculated from the actual sale price of the assets as realized by the corporation. The BIG tax was levied on only $3.5 million because it was limited to the appreciation existing at the time of conversion to S status. The tax paid by the corporation is treated as a deductible loss incurred by T. If gain is realized on more than one BIG asset, the character of such loss is determined by allocating the loss proportionately among the built-in gains giving rise to such tax (Sec. 1366(f )(2)).

Computing the shareholders’ tax and cash flow

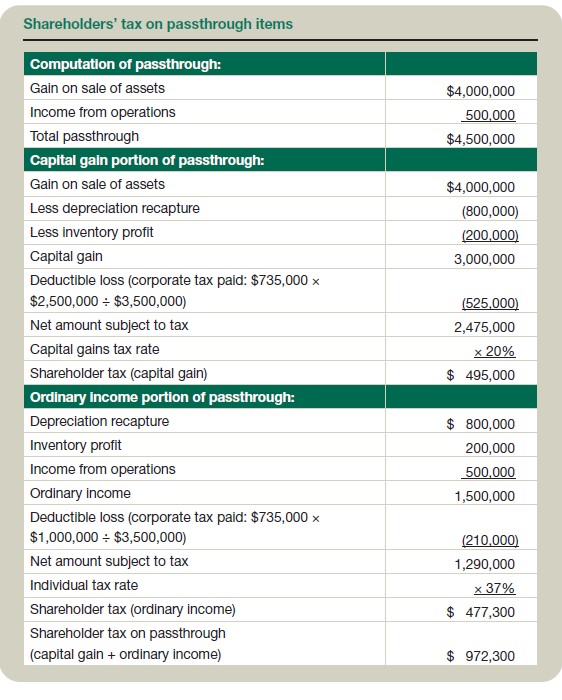

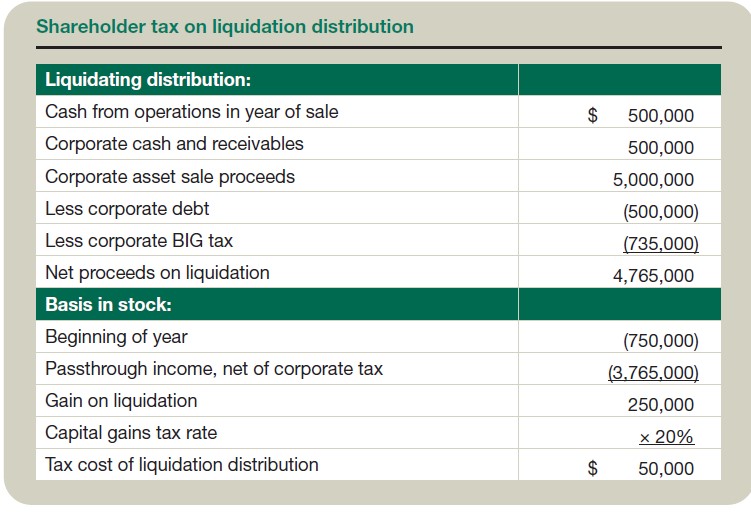

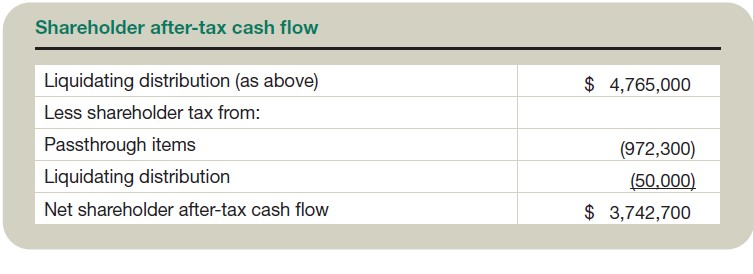

The tax cost and after-tax cash flow to the shareholders is calculated as shown in the tables “Shareholders’ Tax on Passthrough Items,” “Shareholder Tax on Liquidation Distribution,” and “Shareholder After-Tax Cash Flow,” below.

The $735,000 BIG tax is allocated to the capital gain and ordinary income portions of the passthrough in proportion to the types of income giving rise to such tax. For example, since $1 million of the $3.5 million BIG is comprised of ordinary income items (inventory profit of $200,000 plus depreciation recapture of $800,000), approximately 28.57% ($1,000,000 € $3,500,000) of the total $735,000 BIG tax is passed through as a loss that reduces the ordinary income passthrough to the shareholders.

The $735,000 corporate-level BIG tax presents a substantial tax cost to T and its shareholders. T could have avoided this S corporation tax by:

- Being an S corporation for each year of its existence (i.e., never having been a C corporation (Sec. 1374(c) (1) ), or

- Waiting five years after its S election before disposing of its assets (Sec. 1374(d)(7)).

Comparing the results

The calculations discussed in this example show that the extra layer of BIG tax incurred by the corporation generates significant tax to the shareholders. While the corporation incurs $735,000 of BIG tax, this extra tax becomes deductible in computing the net taxable income passthrough to the shareholders. The actual extra tax nets to $552,300 (i.e., $4,295,000 net shareholder after-tax cash flow without the BIG tax, compared with $3,742,700 after-tax cash flow under the BIG tax scenario in this example).

Using the taxable income limit to minimize the BIG tax

The possibility of minimizing the BIG tax by use of the taxable income limit should be explored. In general, the BIG tax is imposed on the lesser of the net recognized BIG or the corporation’s taxable income for the year (Sec. 1374(d)(2)). In this example, the recognized BIG of $3.5 million is substantially less than the overall taxable income of $4.5 million (operating income of $500,000 plus gains of $4 million). In many cases, however, use of compensation, bonuses, and certain built-in losses may produce an operating tax loss capable of offsetting recognized BIG.

Contributor

Shaun M. Hunley, J.D., LL.M., is an executive editor with Thomson Reuters Checkpoint. For more information about this column, contact thetaxadviser@aicpa.org. This case study has been adapted from Checkpoint Tax Planning and Advisory Guide’s S Corporations topic. Published by Thomson Reuters, Carrollton, Texas, 2024 (800-431-9025; tax.thomsonreuters.com).