- feature

- PERSONAL FINANCIAL PLANNING

A retirement savings head start: 529-to-Roth rollovers

Related

Supercharging retirement: Tax benefits and planning opportunities with cash balance plans

Revisiting Sec. 1202: Strategic planning after the 2025 OBBBA expansion

Planning to preserve assets while providing long-term-care options

In the SECURE 2.0 Act,1 passed at the tail end of 2022, Congress included over 100 provisions designed to bolster American savings. One of them allows up to $35,000 of unused funds in a Sec. 529 education savings plan to be rolled over to a Roth IRA for the 529 plan beneficiary. This provision, effective beginning in 2024, creates an opportunity for a 529 account to not only fund a child’s education but also to give them a head start on saving for retirement. While one can rarely predict how much future education a child will wish to pursue — and thus how much education savings will be needed — the rollover strategy can be used as a contingent one in situations where there ends up being a 529 account surplus. Congress made this limited rollover to a Roth possible by enacting new subsection (c)(3)(E) of Sec. 529.

Background on Sec. 529 plans

Congress created Sec. 529 plans in 1996 to make financing the cost of education more manageable for American families. Sec. 529 plans are education-focused accounts that one can open for anyone but are usually used to fund a family member’s education (child, grandchild, niece, nephew, etc.). Taxpayers can make after-tax contributions to 529 plans (often with state tax deductions), and the funds are allowed to grow tax-deferred. Moreover, so long as funds are used to fund qualified education expenses,2 the money can be withdrawn tax-free.3

There are two types of 529 plans: (1) prepaid tuition plans and (2) savings plans. Unlike savings plans, prepaid tuition plans lock in future college tuition rates for designated colleges and universities at current (and presumably cheaper) rates. While 529 plans were designed to benefit middle-class families, statistically speaking, they have yet to have this effect. Sec. 529 plans have been adopted by less than 3% of American households, and most accounts are held by the wealthiest Americans.4

While the original legislation addressed tuition, fees, books, supplies, and equipment, in 1997 Congress permitted room and board to also be paid with 529 plan funds. Congress further enhanced 529 plans in 2001,5 when it made distributions for the beneficiaries tax-free (as opposed to tax-deferred).

Tax and other benefits of 529 plans

There is no federal tax deduction for contributions made to 529 plans. Nonetheless, 529 plans can be an effective way for many to fund a child’s education. For the wealthy, this can be done by taking advantage of the annual gift tax exclusion amount ($18,000 per donee in 2024, or a combined $36,000 for a couple),6 which eliminates the need to file a Form 709, United States Gift (and Generation-Skipping Transfer) Tax Return, or use up any of the taxpayer’s lifetime gift and estate tax basic exclusion amount ($13.61 million per individual in 2024).7 And, as described below, donors can even “front-load” their contribution with five years’ worth of annual gift exclusion amounts all at once.

Because there are no income limits on participation, many affluent families, including 23.9% of households among the highest income decile in 2013,8 have taken advantage of 529 plans to fund education. Amply funded and carefully invested, a single contribution to a 529 plan can grow to provide more than enough money to fund an entire education through tax-free investment growth. Former President Barack Obama’s family is one notable example, having used 529 plans to fund the educational expenses of their two daughters.9

529 plans are also financial-aid friendly, since funds contained in them are classified as the parents’ assets rather than the child’s assets, with only a small percentage of such assets being expected to be contributed to actual educational costs through an expected family contribution.10 Additionally, distributions from a 529 plan account are not considered a taxable gift, making these vehicles attractive from an estate planning perspective.11

Additional changes over the years have increased the attractiveness of 529 plans. For example, beginning in the 2018 tax year, 529 plan accounts can also fund expenses of attending an elementary or secondary public, private, or religious school.12 However, only tuition qualifies as an eligible 529 expenditure in this case and is limited to $10,000 per beneficiary per year. Additionally, 529 plan accounts can be used to pay principal and interest on student loans up to $10,000.13 Finally, while the federal government does not permit a tax deduction for 529 contributions, most states provide a tax benefit.14 Besides the nine states that do not have a state income tax and therefore do not have a state income tax deduction, all but four provide a deduction or tax credit for 529 contributions.15

A common problem: Stranded dollars and 529 overfunding

One noteworthy option is to elect to “front-load” or “superfund” 529 plan accounts with up to five times the annual gift exclusion, with the aggregate amount taken into account ratably over the five-year period beginning with the calendar year of donation.16 Thus, a married couple with two children could contribute $180,000 in 2024 to an account for each child (the $36,000 annual gift exclusion × 5), or $360,000 for their two children combined. For high-wealth donors, this feature enables the immediate transfer of money out of a taxable estate and into an account where it can grow tax-free for many years.17

A considerable amount of disposable income would be needed to fully fund a 529 plan account in this way, and one can see that a tax provision designed to benefit the middle class could be used as an estate planning tool for the wealthy.18 Also evident is that a 529 plan account initially funded for a young child could grow to a substantial amount before the child’s interests and ambitions are fully developed. Thus, such an option, without the ability to transfer excess funds out of the 529 plan account, could trap those funds there. And any amount could become such an excess if the child decides not to go to college or chooses to attend an institution that does not participate in a Department of Education–administered federal student aid program.

Where a 529 plan account is over-funded relative to eligible educational expenses, trapping funds there, the owner and beneficiary have traditionally been placed in a quandary. Moreover, to the extent a distribution of earnings in a 529 plan account is made for nonqualified expenses, the distribution is generally considered taxable income to the distributee.19 In addition, a distribution of funds from a 529 plan account for nonqualified expenses carries a 10% penalty to the extent the distribution is includible in income.20 In such an event, an owner of a 529 plan account would be left to try to find an exemption to the penalty and the inclusion in taxable income for distributions of the residual amount from the account.

Many financial planners and their clients have rightfully been concerned about stranding funds in a 529 account. Likewise, policymakers have recognized that parents’ and grandparents’ worries about funds becoming trapped might disincentivize them from amply funding or even opening a 529 plan.

A partial solution: 529-to-Roth conversions

Responding to this problem, lawmakers included a provision in the SECURE 2.0 Act that can help free a limited amount of funds held in a 529 plan account. Beginning in 2024, 529 account owners can roll over up to $35,000 of unused 529 funds to a Roth IRA for the beneficiary of the 529 plan — without incurring the 10% penalty for nonqualified withdrawals and without creating additional taxable income.21

There are some rules to be aware of. First, the funds cannot revert to the founder/owner of the 529 but must be transferred to a beneficiary. Additionally, the account must have been open for more than 15 years.22 Further, no fund contributions from the past five years or earnings on those contributions may be rolled over. It follows that last-minute beneficiary by front-loading a 529 plan, circumventing gift tax provisions, may prove unfruitful.

Moreover, the penalty- and tax-free transfers must occur annually and cannot exceed the maximum contribution limits for a Roth IRA in effect in the transfer year.23 This rule means that any authorized Sec. 529 rollovers will be subject to a limit of the lesser of the annual applicable Roth contribution limit ($7,000 for tax year 2024) or the beneficiary’s earned income, less the aggregate amount of contributions made during the tax year to all individual retirement plans maintained for the benefit of the beneficiary. Consequently, under current circumstances, it will take at least five years to convert the allowed $35,000 to a Roth account. Finally, a Roth conversion must be made in a direct trustee-to-trustee transfer.24

A retirement savings head start

Because of the difficulty of predicting how much a particular child will need in education funding, a 529-to-Roth roll-over generally cannot be planned years in advance but can be a contingent strategy that makes use of any surplus in the 529 plan account.

The following example illustrates how a rollover could give a child a head start on retirement savings when a 529 plan account turns out to be slightly overfunded relative to the child’s eligible education expenses.

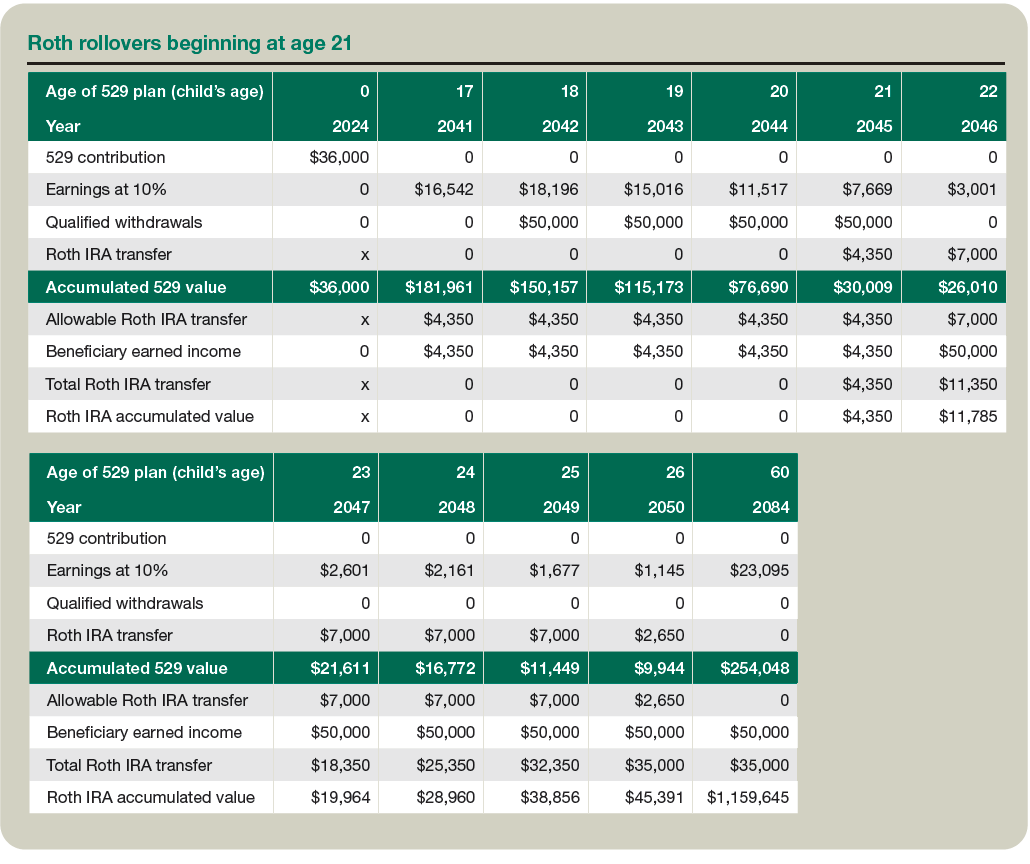

Example: A child’s grandparents make a one-time contribution of $36,000 to a 529 savings plan in 2024 on the day of his birth. Assume the fund earns 10% annually. The child starts working part time when he turns 16 and earns $4,350 annually. The child enrolls in college at age 18, when the 529 account has accumulated a value of $181,961, and withdraws $50,000 annually for qualified education expenses for four academic years. After withdrawing the final $50,000 of qualified expenses at age 21, $34,359 of unused funds would remain in the 529 account. In that same year, the grandparents initiate the first rollover into a Roth IRA of $4,350, equal to the child’s earned income (see the table “Roth Rollovers Beginning at Age 21,” below).

Provided the child, after graduating, has at least $7,000 of earned income, the full Roth contribution limit of $7,000 could be transferred annually thereafter until a final rollover contribution of $2,650 exhausts the maximum rollover limit of $35,000 at age 26 (assume for these purposes that the Roth contribution limit remains $7,000). Given a 10% annual return within the Roth IRA, left untouched, this seemingly insignificant $35,000 retirement contribution resulting from the rollover could appreciate to a value of $1,159,645 when the child reaches age 60. However, this transfer strategy would still leave $9,944 stranded in the 529 account.

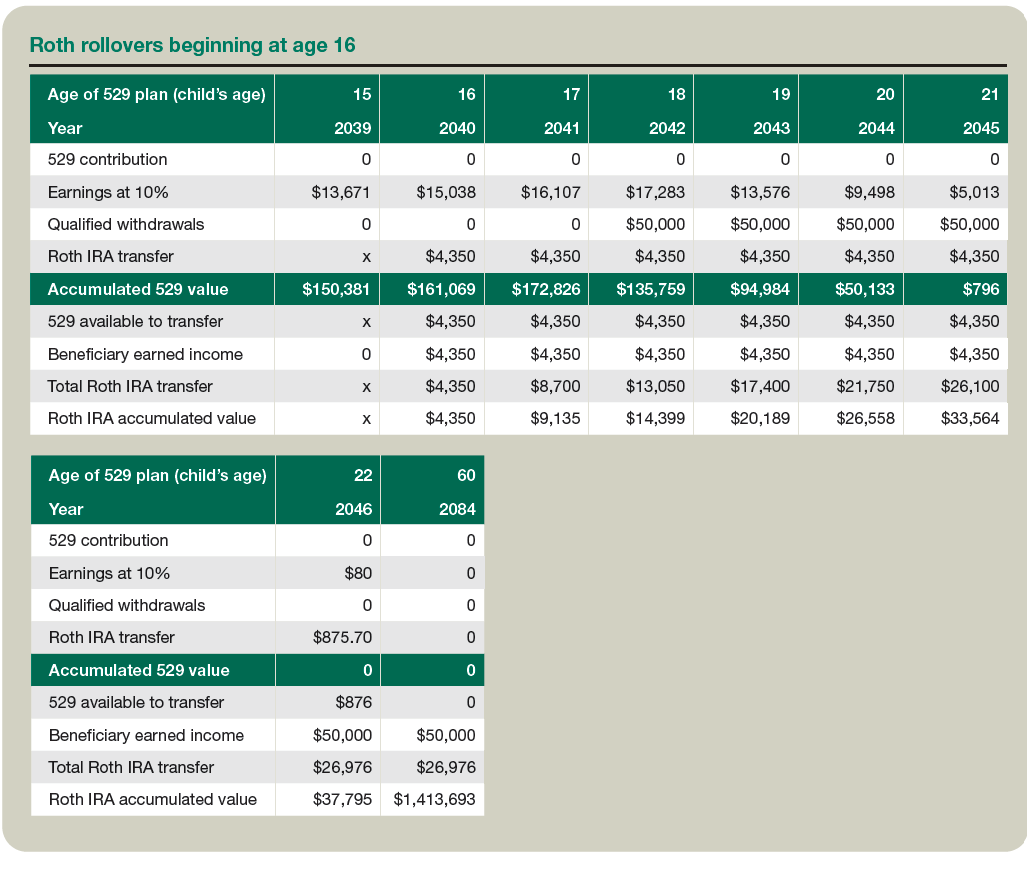

These funds remain trapped in the 529 plan account even though the balance after the final qualified withdrawal was less than $35,000. The reason is because, if earnings in the account compound annually at 10%, any balance greater than $26,535 would leave some funds stranded in an account if Roth transfers are not initiated until the year after the last qualified withdrawal. As seen below, the optimal strategy here to avoid stranding funds could be to initiate a rollover as soon as one is allowable when the child turns 16, so long as it is clear the funds will not be needed for education.

Suppose, then, that the grandparents initiate a Roth transfer at age 16 of $4,350 (equivalent to the child’s earned income) and do so annually while the child remains working part time during college. The final $50,000 withdrawal would leave $796 in the 529 plan account. One final Roth transfer of $876 at age 22 would deplete the account and contribute a total of $26,976 to the child’s Roth IRA. Although this rollover strategy would contribute fewer total dollars to the Roth IRA, via compounding, this strategy would accumulate more dollars at age 60 ($1,413,693) than a full $35,000 rollover initiated at age 21 ($1,159,645), and no funds would be left stranded in the 529 plan account (see the table “Roth Rollovers Beginning at Age 16,” below).

An enhanced savings tool

Post-SECURE 2.0 Act, donors need not worry quite so much about the possibility of overfunding a 529 plan. If the 529 plan ends up having a surplus, a rollover to a Roth IRA will give the child a head start on saving for retirement. As in the above example, up to $35,000 could be rolled over into a Roth at a young age and invested tax-free for the rest of the child’s life, perhaps 60 or more years. With the value of compounding, this would be a significant benefit and would influence the child’s life decades and decades into the future.25

A further benefit is that Roth funds can also be used for certain purposes besides retirement, such as a first-time home purchase (see Long, “3 Strategic Uses for Roth IRAs Beyond Retirement,” Journal of Accountancy (Aug. 2, 2022)).

While 529 plans will continue to be a critical planning resource for education savings, the SECURE 2.0 Act has made this tool even more potent because, if some of the funds in the 529 account are not needed for education, the parent or grandparent can choose to give the child a head start on their retirement savings.

Footnotes

1SECURE 2.0 Act, Division T of the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2023, P.L. 117-328.

2Sec. 529(e)(3).

3Sec. 529(c)(3).

4Pressman and Scott, “The Higher Earning in America: Are 529 Plans a Good Way to Save for College?” 51(2) Journal of Economic Issues 375–82 (2017).

5Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001, P.L. 107-16.

6Secs. 2503(b)(1) and (2); Rev. Proc. 2023-34, §3.43.

7Rev. Proc. 2023-34, §3.41.

8Hannon, Moore, Schmeiser, and Stefanescu, “Saving for College and Section 529 Plans,” FEDS Notes (Federal Reserve, Feb. 3, 2016).

9“The First Family’s 529 Windfall” (editorial), The Wall Street Journal (Jan. 23, 2015).

10Zhuang, “Two Must-Have Client Conversations for College Planning: 529s, FAFSA,” Financial Planning (2023).

11Sec. 529(c)(5)(A).

12Sec. 529(c)(7).

13Sec. 529(c)(9).

14Reschovsky, “Higher Education Tax Policies,” in The Effectiveness of Student Aid Policies: What the Research Tells Us, Baum, McPherson, and Steele, eds. (The College Board 2008).

15Lake, “529 Plan Tax Deductions for Every State,” Smart Asset (June 29, 2023).

16Sec. 529(c)(2)(B).

17Bloink and Byrnes, “Should Your Clients ‘Superfund’ Their 529 Plans?” ThinkAdvisor (2022).

18If a married couple max out front-loaded 529 contributions in a child’s birth year, the fund’s value may exceed educational expenses by a wide margin.

19Sec. 529(c)(3).

20Sec. 529(c)(6); Sec. 530(d)(4).

21Sec. 529(c)(3)(E).

22Sec. 529(c)(3)(E)(i).

23Sec. 529(c)(3)(E)(ii)(I).

24Sec. 529(c)(3)(E)(i)(II).

25A five-year, $7,000 annual 529-to-Roth conversion initiated at age 18 and finalized at age 22, left untouched, would appreciate to $1,598,501 at age 60, given a 10% annual return.

Contributors

Patrick Ryle, CPA, J.D., LL.M., CMA, is an assistant professor of accounting; Michael P. D’Itri, Ph.D., is a professor of supply chain management; and Caleb S. Watkins, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of economics, all at Dalton State College in Dalton, Ga. For more information about this article, contact thetaxadviser@aicpa.org.

AICPA & CIMA RESOURCES

Articles

Demosthenes, “529 Plans and Education Funding,” 54-9 The Tax Adviser 50 (September 2023)

Long, “Saving for College With Multiple Children: New Considerations,” Journal of Accountancy (Aug. 22, 2023)

Toolson, “The Unique Benefits of 529 College Savings Plans,” 54-5 The Tax Adviser 30 (May 2023)

Podcast episode

“Strategies to Draw Down Excess 529 Funds,” AICPA Personal Financial Planning podcast (April 11, 2024)

Tax Section and Personal Financial Planning Section resource (members only)

Tax and Financial Planning Tips: Education Costs

Personal Financial Planning Section resource (members only)

Visualizing Roth Changes From SECURE Act 2.0

CPE self-study

For more information or to make a purchase, visit aicpa.org/cpe-learning or call 888-777-7077.