- feature

- exempt organizations

Planning for private foundation grantmaking

Related

IRS rules that community trust and affiliated nonprofit corporation can file a single Form 990

Effects of the OBBBA on higher education

Paid student-athletes: Tax implications for universities and donors

This article addresses how private foundations can plan their grantmaking for optimal results while complying with the requirement under Sec. 4942 to annually distribute a minimum amount of assets for charitable purposes. This discussion will:

- Demonstrate how a typical private foundation can meet the Sec. 4942 distribution requirement by making, if it wishes to do so, a single lumpsum distribution that is treated as distributed over seven years and highlight the advantages of employing this one-time substantial-distribution approach based on market conditions to bolster significant charitable projects.

- Offer a clear-cut strategy for private foundations to implement market-driven distribution methods for long-run sustainability, with an assessment of the benefits, drawing on historical market data.

- Delve into the historical background of the relevant legislation and emphasize the importance for private foundations to adapt to evolving market dynamics in the future.

The ideas explored herein can help foundations support large charitable endeavors, safeguard the value of their assets, and enhance their capacity for long-term grantmaking.

Tax rules relating to private foundation distributions

Before discussing planning strategies for grantmaking, it is worthwhile to give some background on the tax principles of Sec. 4942 that underpin private foundation distributions. Relevant key terms include “distributable amount,” “undistributed income,” and “excess qualifying distribution carryover.”

Distributable amount and qualifying distributions

According to Sec. 4942, a nonoperating private foundation is required to calculate and annually distribute a minimum amount of assets for charitable purposes or face an excise tax on the undistributed amount (referred to in Sec. 4942(c) as “undistributed income”). The amount that must be distributed each year is the “distributable amount,” which is the foundation’s “minimum investment return” with some adjustments. A foundation’s minimum investment return for a tax year is equal to 5% of the fair market value of its assets that are not directly used or held for use in carrying out its exempt purpose, over those assets’ acquisition indebtedness.1 A foundation must pay out the distributable amount in the form of “qualifying distributions” under Sec. 4942(g), which are essentially grants, outlays for administration, and direct purchases of charitable assets.

Undistributed income

Sec. 4942(c) defines “undistributed income” as the amount by which the distributable amount for a given tax year exceeds the qualifying distributions allocated to that year made by the foundation. The foundation must pay out the distributable amount for a year by the end of the year following the year for which the distributable amount was calculated or pay the Sec. 4942 excise tax on the undistributed amount (i.e., undistributed income). Therefore, a foundation has 365 days to make distributions of the distributable amount for a year after the close of the year to avoid the Sec. 4942 excise tax.

Excess qualifying distributions carryover

The general rule in the regulations under Sec. 4942 stipulates that during a tax year, any qualifying distribution is allocated in the following order: It is deemed to be made (1) out of the undistributed income of the immediately preceding tax year; (2) out of the undistributed income of the current tax year to the extent available; and (3) out of the foundation’s corpus.2 If a foundation makes qualifying distributions that exceed the current year’s distributable amount and the previous tax year’s undistributed income, it has created “excess qualifying distributions.”3 The foundation may use such excess distributions to reduce the distributable amount in any of the five tax years immediately following the tax year in which the excess is generated.

However, the distributable amount for any of those subsequent five years cannot be reduced by more than the remaining undistributed income at the end of the tax year, after factoring in the qualifying distributions made in that year toward that same year’s distributable amount. If, during any tax year during the five-year period, another excess of qualifying distributions is created, these excess qualifying distributions are not taken into account until the excess qualifying distributions from the earlier year have been completely applied against distributable amounts during the five-year period. Accordingly, the regulations apply a first-in, first-out method for utilizing excess distributions.4

Penalties for failure to distribute income

A foundation that fails to distribute the required amount could face three tiers of excise taxation. These excise taxes are known, respectively, as the initial tax under Sec. 4942(a), the additional tax under Sec. 4942(b), and the involuntary termination tax under Sec. 507(c). The initial excise tax rate is 30% of the undistributed amount. This tax is reported on Form 4720, Return of Certain Excise Taxes Under Chapters 41 and 42 of the Internal Revenue Code.

The second-tier tax, equal to 100% of the undistributed income, applies if the situation is not corrected at the end of the “correction period,” which ends 90 days after the mailing date of a statutory notice of deficiency assessing the tax. The managers and officers of a foundation subject to the additional tax under Sec. 4942(b) can, under certain circumstances, be held personally responsible for this tax. If, after being assessed the first and second tiers of excise tax, a foundation still fails to distribute income, the IRS could impose the involuntary termination tax under Sec. 507(c); this confiscatory tax is calculated as the lower of two amounts: (1) the aggregate tax benefit derived from the foundation’s tax-exempt status or (2) the value of the foundation’s net assets.

The taxes are as hefty as their rules are stringent. In 2022, a total of 2,232 Forms 4720 were submitted to the IRS, reflecting payments amounting to $25,275,506 in first- and second-tier excise taxes on undistributed income, averaging $11,324 per tax return.5

Two planning ideas

Despite the strictness of the distribution rules — and setting aside the risk of large excise tax liabilities — these rules nonetheless give foundations enough flexibility both to fund large charitable projects and achieve long-term growth in the value of their assets, as is shown below.

Planning to support large charitable projects

Clients in search of opportunities to undertake or support large charitable projects often ask: “What is the maximum amount a foundation can give in a year?” The IRS has set no upper limit. Indeed, the penalties apply only to the failure to distribute sufficient income; they do not contemplate the distribution of “too much” income. However, nontax issues arise in this context. Under state laws, foundation officials typically have a fiduciary duty to protect a foundation’s corpus in perpetuity; moreover, most foundations’ establishing documents express this expectation.

Taken together, the rules discussed above point to a seven-year grantmaking cycle. Specifically, a foundation’s undistributed income in year 1 can be distributed in year 2, and the excess distribution credit in year 2 can be used for the next five years, thus establishing this sevenyear period.

A useful strategy emerges from this seven-year grantmaking cycle: By distributing in one year the total distributable amount for seven years, a foundation can more easily support large philanthropic projects.

Examples 1 and 2 demonstrate this strategy. Assume that a foundation has $10 million in assets at the start of year 1 and that a local charity seeks $3 million–$4 million for a project for the next two years. Foundation trustees want to help but lack clarity on whether the foundation can make such a large distribution while maintaining its asset base and remaining compliant with Sec. 4942.

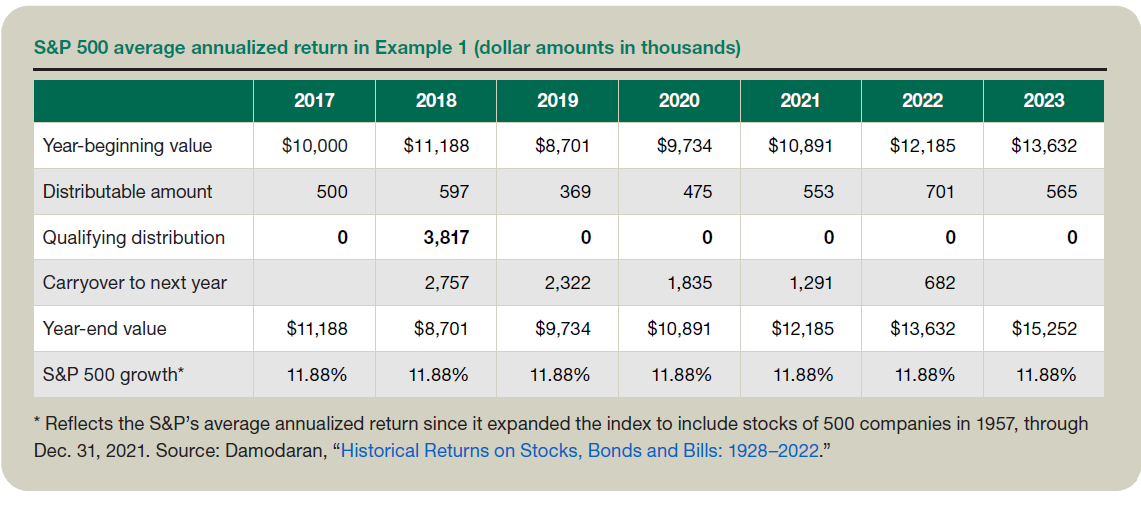

Example 1: This example uses the average annualized return of the S&P 500 to project the foundation’s asset value and the distributable amount over seven years. To simplify this calculation, assume that the distributable amount is equal to 5% of each year’s initial value and that the foundation has no qualified charitable expenses other than with respect to charitable grants.

The table “S&P 500 Average Annualized Return in Example 1,” below, shows that the foundation should undertake some planning, because refraining from making a distribution in year 1 is critical to maximizing the charitable distribution. Making no distribution in year 1 enables the foundation to make a $3.817 million distribution in year 2. This large payment is the sum of distributable amounts from years 1–7; that is, year 1’s undistributed income and year 2’s distributable amount and excess distributions to cover the forthcoming five years of required distributions. By the end of year 7, all excess qualifying distribution carryover will have been used. The year 2 qualifying distribution of $3.817 million can be called “the equilibrium point” because it is based on the long-term annualized return rate. Given any year as year 1, the equilibrium point for year 2 will be a known figure.

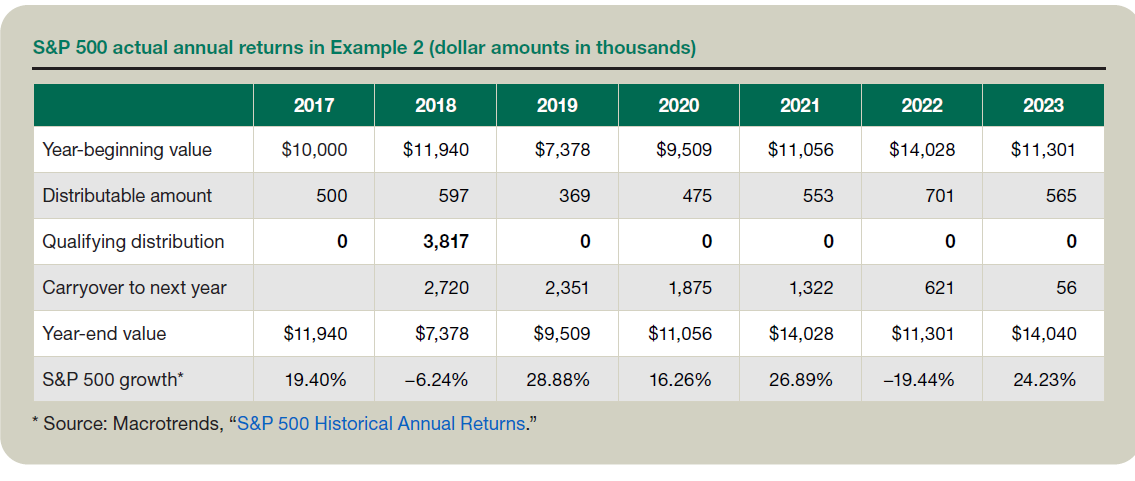

Example 2: This example applies real-world numbers to the investment return. Assume that year 1 is 2017. Applying the equilibrium point to the actual standard S&P annual returns for 2017–2023 generates the results seen in the table “S&P 500 Actual Annual Returns in Example 2,” below.

If the foundation makes a one-time grant distribution of $3.817 million in 2018, by the end of 2023 there will be no penalties under Sec. 4942 (with a $56,000 excess in distribution to expire). The total value of the assets will be $14.04 million, representing an asset appreciation of 40.4% over the seven-year period.

Planning long-term asset value growth

So far, the discussion has centered on funding large charitable projects. The focus now turns to grantmaking strategies for achieving long-term growth in the value of a foundation’s assets. As shown above, the tax rules allow flexibility for foundations to make grants based on market conditions. This flexibility also represents an opportunity to plan to stabilize asset value and achieve long-term asset value growth, which are important goals for most governing bodies of private foundations.

To simplify the analysis of grantmaking strategies for growing assets, the years under consideration can be divided into two market-condition categories: a bull market (“up”) and a bear market (“down”).

The 2023 (year 7) year-end asset value in the table “S&P 500 Actual Annual Returns in Example 2” is less than that created by the historical S&P average return used in the first table. One reason for this is that the second table makes the distribution in a “down” year (2018), when the S&P 500 shrank 6.24%.

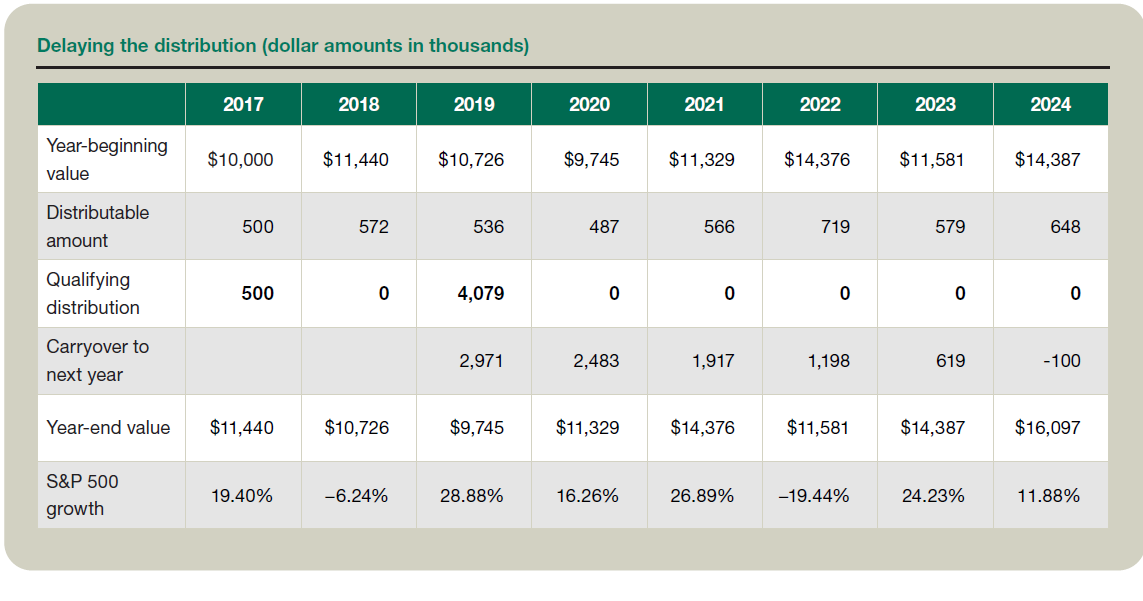

Delaying the distribution to an “up” year might show a markedly different result, as the third table, “Delaying the Distribution,” below, shows; this table also demonstrates how, with distribution in year 3 (2019), year 2 becomes the initial year of the seven-year grantmaking cycle, extending it to year 8. The equilibrium point is then at $4.079 million.

“Delaying the Distribution” applies the equilibrium to the actual annual returns for 2018–2023 and assumes the annual return rate for 2024 is the longterm annualized rate of 11.88%.

Comparing the “Delaying the Distribution” results with those of the table “S&P 500 Actual Annual Returns in Example 2” shows that by moving the distribution forward a year to 2019 — an “up” year — growth in the assets’ value notably improves. The foundation would have been able to make $262,000 more in grant payments ($4.079 million – $3.817 million) and would have had $347,000 more in assets ($14.387 million – $14.040 million) through the end of 2023. Note that a grant of $100,000 would need to be made in 2024.

One might think that the growth in asset value in Example 2, as modified, is just an extreme case resulting from the fact that the foundation made a one-time, lump-sum distribution over the course of seven years. However, Example 3 examines a typical situation, one where a foundation desires to make annual distributions.

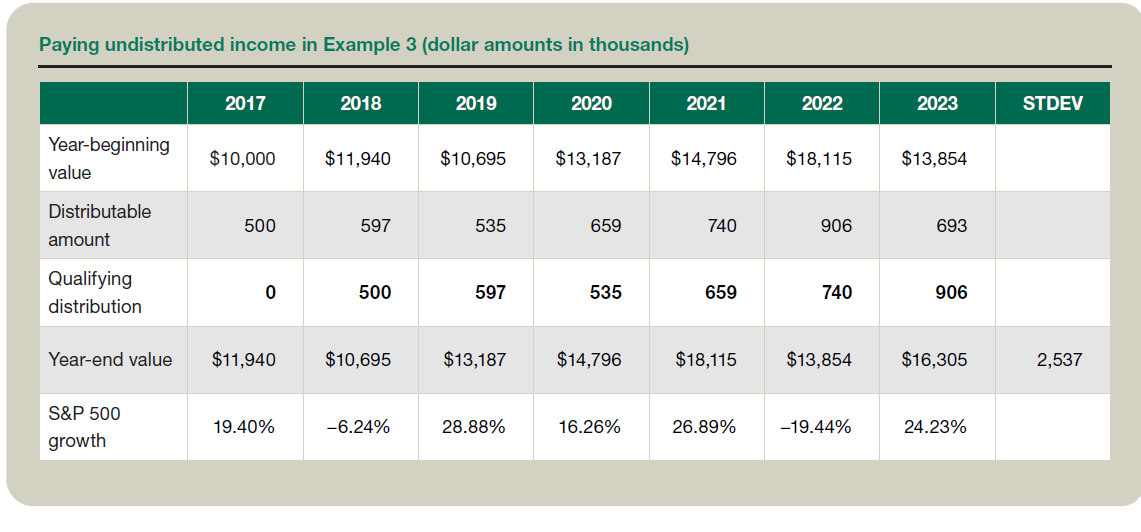

Example 3: The foundation does not engage in grantmaking planning based on stock market conditions. Rather, it simply pays out the preceding year’s undistributed income to meet the distribution requirement. The foundation will then have an asset value of $16.305 million by the end of 2023, as the table “Paying Undistributed Income in Example 3,” below, shows. The standard deviation of its year-end values, an indication of the stability of the foundation’s asset value over the period, is 2,537.

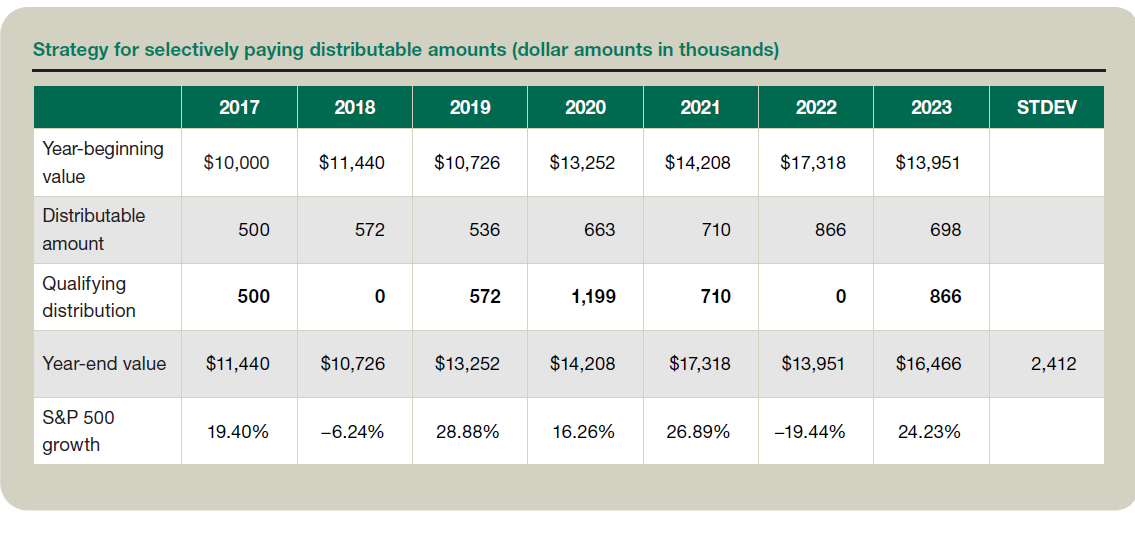

Next, the table “Strategy for Selectively Paying Distributable Amounts,” below, examines what results if the foundation adopts a strategy to base grant payments on market conditions, as follows:

- If, in the first year of the planning time frame, the market is “up,” the foundation would pay out the currentyear (2017) distributable amount and do the same for any consecutive up years (including 2019–2021).

- If, on the other hand, the market experiences a “down” year (2018 and 2022 in the table), the foundation would defer the distribution for that year until the following year. If there are two consecutive “down” years, the foundation would simply pay out the previous year’s undistributed income in order to meet the distribution requirement.

- In an “up” year that follows a “down” year, the foundation would pay out only the undistributed income (2019 and 2023), giving the market one more year to recover.

- For any two consecutive “up” years, the foundation would bring the distribution status current in the second such year (2020).

By executing this strategy, the foundation will have distributed all current- and prior-year undistributed income in three of the seven years (2017, 2020, and 2021).

The year-end value of the foundation’s assets for 2023 is $161,000 more than that shown in the table “Paying Undistributed Income in Example 3.” Perhaps surprisingly, the standard deviation of the asset values at the end of 2023 is also significantly less. In other words, the grantmaking planning strategy based on market conditions not only creates (in this scenario) more asset growth, it also helps to stabilize the foundation’s asset value over the years involved.

The examples in this article deliberately employ a seven-year time frame; for a foundation, however, such a duration is not considered long term. In fact, the longer the strategy is employed, the greater the likely benefit. For instance, assume the foundation in the examples had been established and funded with $10 million in 1969, the year Sec. 4942 was enacted.6 Also assume the payout rate is always at 5% to simplify the calculation. If this foundation had faithfully implemented this strategy — that of basing grant payments on market conditions — from its inception through 2022, it would have maintained current status on distributions for 28 of those 53 years. Compared to merely distributing the prior-year undistributed income for the same period (and assuming a 50-basis-point management fee), one could expect to see this strategy result in an additional $1.256 million in asset value and $51,000 added to the 2023 distributable amount.

Adapting to market dynamics

Lawmakers established Sec. 4942’s distribution requirement to ensure that, rather than hoarding their wealth, private foundations would actively put it to philanthropic use. As originally adopted in 1969, the minimum investment return was based on a 6% rate; this rate for determining minimum investment return was changed to 5% for years after 1976. The original choice of 6% might be attributable to contemporary economic data; for 1930–1970, the average real annual growth rate in the United States was 3%–4%7 and the long-term inflation rate averaged 2%–3%.8 Considering outlays for administrative expenses, the 6% rate was a reasonable choice for a foundation to maintain its value in real terms, particularly when coupled with the underlying assumption that its assets would be diversified across all capital markets in a perfectly competitive market status.

The two-year payout period and five-year carryover were also likely based on economic data and research. Economists determined that the average macroeconomic cycle was approximately seven years, a phenomenon later referred to as the “Burns seven-year cycle.”9

Whatever the reasons for the provisions, private foundations have operated well under them for over 50 years. The typical private foundation, benefiting from long-term economic growth and the phenomenal performance of the stock market, has not only met all distribution requirements but also enjoyed significant growth in the value of its assets. However, as the fundamentals of the economy change over time, private foundations may need to adapt to market dynamics to meet the current 5% distribution requirement over the long haul.

For 2000–2022, the average U.S. real annual growth rate has dwindled to just over 2%.10 If the inflation rate drops to 2%, as is the Federal Reserve Bank’s aim,11 a private foundation could encounter challenges in maintaining its corpus over time, particularly when it is required to distribute 5% of its assets.

A payout rate that exceeds the growth rate could erode a foundation’s real asset value. Grantmaking strategies like those outlined in this article could allow private foundations to safeguard the value of their assets in real terms and optimize the impact of their philanthropy.

Footnotes

1Secs. 4942(d) and (e)(1)(A). A foundation must value these assets annually by procedures outlined in Regs. Sec. 53.4942(a)-2(c).

2Regs. Sec. 53.4942(a)-3(d)(1).

3Sec. 4942(i).

4Regs. Secs. 53.4942(a)-3(e)(1) and (4), Example 1.

5IRS Statistics of Income, Domestic Private Foundation and Charitable Trust Statistics, Table 1, Excise Taxes Reported by Charities, Private Foundations, and Split-Interest Trusts on Form 4720.

6Tax Reform Act of 1969, P.L. 91-172.

7U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Table 1.1.1. Percent Change From Preceding Period in Real Gross Domestic Product.

8U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Table 1.1.7. Percent Change From Preceding Period in Prices for Gross Domestic Product.

9This designation honors Arthur Burns, who assumed the role of Federal Reserve Bank chairman in 1970 and is credited with being the first to observe this pattern.

10U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Table 1.1.1. Percent Change From Preceding Period in Real Gross Domestic Product.

11Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FAQs, “Why Does the Federal Reserve Aim for Inflation of 2 Percent Over the Longer Run?”

Contributor

Yong Shuai, CPA, Ph.D., CFA, is a vice president and manager of foundation and charitable trust tax at Glenmede Trust Company, N.A., in Philadelphia. For more information about this article, contact thetaxadviser@aicpa.org.

Author’s note: The author would like to thank Kenneth Spruill, director of the Center for Family Philanthropy and Wealth Education at Glenmede Trust Company, N.A., and Robert Maxwell, senior estate accountant at Morgan Lewis & Bockius LLP and adjunct professor of law at Villanova University Charles Widger School of Law, for their invaluable contributions and insightful comments. Any errors or omissions are the author’s responsibility.

AICPA & CIMA RESOURCES

Article

Liang, “Scholarship Grants Awarded by Private Foundations,” 53-11 The Tax Adviser 10 (November 2022)

Podcast episode

“How to Choose Between a Donor Advised Fund and a Private Foundation,” Sept. 30, 2023

Tax Section member resource

2023 Private Foundation Engagement Letter — Form 990-PF

Not-for-Profit Section member resources

Most Common Form 990-PF Preparation Errors

Not-for-profit grants and contracts FAQs

For more information or to make a purchase, visit aicpa-cima.com/cpe-learning or call 888-777-7077.

CPE self-study

Not-for-Profit Tax Compliance