- column

- PERSONAL FINANCIAL PLANNING

What to do when a client dies

Related

IRS broadens Tax Pro Account for accounting firms and others

Representing taxpayers with IRS identity protection and theft victim assistance

New law, IRS workforce cuts raise red flags for tax season, reports say

Editor: Theodore J. Sarenski, CPA/PFS

The process of estate and trust administration after a CPA client’s death can vary in complexity, depending on each situation’s facts and circumstances. Factors requiring consideration can include legal property rights, the titling of assets, and the implications of income and transfer taxes. In some cases, a court proceeding, or probate, may be required. To illustrate some of the tax complexities CPAs may face in these situations, a fictitious sample fact pattern follows.

On March 2, 2024, you receive a call from your client, K, that her husband, J, passed away unexpectedly the day before. Though J and K had been married for many years, this was a second marriage for both, and they both have a child or children from a previous marriage. K’s relationship with her stepchildren is cordial, but she wants to make sure she is doing things properly as the representative of the estate. She needs your advice on the estate’s federal estate and income tax obligations and other next steps.

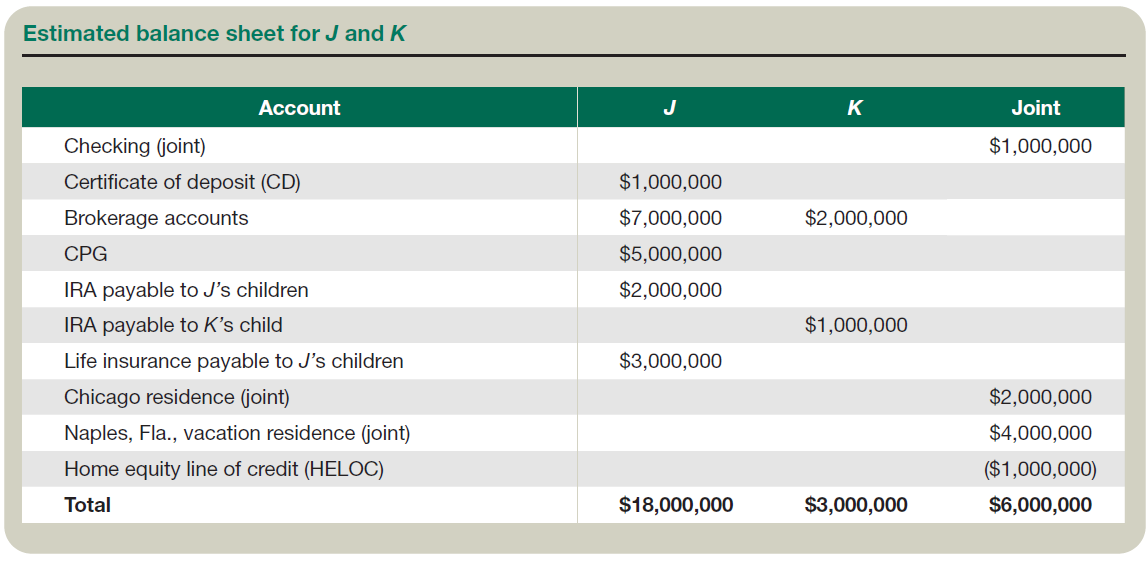

K has provided you with an estimated balance sheet, which includes J’s 51% interest in CPG, an S corporation that J established with two other colleagues (see the table, “Estimated Balance Sheet for J and K,” below).

K has experienced numerous health concerns, and J established a spousal lifetime access trust (SLAT) funded with $5 million two years ago to provide for her. As part of that planning, K and J updated their wills and revocable trust agreements. J’s will provides that his assets pour over to his living trust, which in turn creates a family trust funded with his unused applicable exclusion amount and a qualified terminable interest property (QTIP) marital trust for K. Thus, although his gross estate will exceed the basic exclusion amount, it is expected to be nontaxable. The only asset currently titled in the name of J’s living trust is CPG.

Next week, you are meeting with K, her attorney, and her investment adviser to discuss the estate’s federal estate and income tax obligations. Let’s consider your agenda for the meeting.

Estate administration basics

Different parties play different roles in estate administration. K, as the named representative in J’s will, is responsible for carrying out its provisions. In some cases, a probate proceeding in the local court may be required to permit K to sign in her capacity as representative to effectuate the transfer of assets from J’s name to the trust. If the assets to be transferred are minimal in value, applicable state law may provide for a streamlined probate process or the use of an affidavit instead of a full probate proceeding.

A probate proceeding will often extend the period of the estate’s administration due to the required notices to interested parties and potential creditors. Creditors have up to six months to file a claim against the estate for any unpaid debts. (This rule varies by state. A detailed analysis of a creditor’s right to make a claim against an individual’s estate is beyond the scope of this column.) An accounting of all receipts and disbursements may also need to be prepared and filed prior to closing the court proceeding. The accounting can be waived by the beneficiaries.

If all of the named representatives in a will are unavailable or decline to act, or in the absence of a will, state law sets forth the priority under which a family member can appoint a representative to administer the estate.

Tax implications

The federal estate tax basic exclusion amount is $13,610,000 in 2024, and a federal estate tax return must be filed if the gross taxable estate plus prior gifts exceed this amount. In addition, 13 states and the District of Columbia currently have a separate estate or inheritance tax for which additional estate tax filings may be required. For income tax purposes, the estate and the now irrevocable trust became separate income taxpayers at J’s passing. An election can be made to combine them, as described below.

All of J’s assets that he controlled at his passing will be includible in his estate. As discussed more fully below, J’s gross taxable estate may include more than the assets owned at death. Because the will names the trust as the only beneficiary of the probate estate, the trust’s terms will dictate the administration and distribution of J’s assets, and K, as trustee, must administer the trust pursuant to its terms.

Beneficiaries may receive assets through the trust or may receive assets by operation of law, i.e., through joint tenancy with rights of survivorship or tenancy by the entireties, or through a pay-on-death or beneficiary designation. For example, J’s IRA and life insurance will pass directly to the designated beneficiaries. Given that the checking account and residences are titled as joint tenancy with rights of survivorship, those will pass to K automatically.

Common considerations immediately following a client’s death

As representative, K has a duty to secure the estate’s assets. Some steps that she might take include:

- Alerting the Social Security Administration of J’s death;

- Canceling J’s credit cards and driver’s license to protect against identity theft;

- Closing personal email and social media accounts;

- Notifying financial institutions;

- Securing homes and storage facilities and their contents;

- Safeguarding specific gifts or items of sentimental value;

- Confirming that any firearms are properly secured and custodied;

- Ensuring that cryptoasset wallets are secure;

- Canceling monthly subscription contracts;

- Alerting life insurance companies and requesting payout; and

- Estimating cash flow demands for immediate needs, including funeral and burial expenses.

K should also order a number of death certificates to assist in getting assets retitled and benefits such as life insurance paid. One will be needed for the estate tax return filing, each financial institution in which J had an account, and each life insurance policy for which J was an insured.

Basics of estate assets

An estate tax return — Form 706, United States Estate (and Generation- Skipping Transfer) Tax Return — provides, at a minimum, a snapshot of the decedent’s financial situation on an accrual basis on the date of death (or alternate valuation date, if elected). The gross estate includes not only what the decedent owned at the date of death but also property that the decedent had the right to take under a general power of appointment under Sec. 2041. It also includes assets that the decedent previously owned but retained an economic interest in or could control the beneficial enjoyment of at the date of death.

You know from the estimated balance sheet that J’s net assets are around $21 million ($18 million of separate property plus his $3 million share of joint property) and that he also made $5 million of taxable gifts during life. Consequently, he will have an estate tax filing requirement. Based on preparing his income tax returns for the last few years, you are also aware that J had a collection of rare coins, several cars, and significant tangible personal property between the two homes. Thus, you should review and refine the estate inventory with K and her attorney to ensure all assets are listed. Consider asking K for a copy of their home insurance policies to discover if other substantial assets are listed on the riders.

In the initial meeting, you should also confirm with the attorneys that you have the most updated copies of the will and living trust. It is not uncommon for there to be multiple amendments and restatements of living trusts as clients’ family circumstances and objectives change. Helping K understand what assets (and beneficial interests in trusts) she is entitled to under the documents will be critical to her peace of mind. Having K’s investment adviser at this meeting to understand the disposition plan and the decisions related to trust funding will allow the adviser to better assist K with cash flow planning.

Key tax dates and elections

J and K’s final joint income tax return will be filed for 2023, including J’s income earned prior to death. Income earned thereafter on his individually held assets will be taxed to his estate on a Form 1041, U.S. Income Tax Return for Estates and Trusts. Given that J’s trust became irrevocable at his death, income from assets held in it (i.e., CPG) will be taxed on a separate Form 1041 unless a Sec. 645 election is made.

A Sec. 645 election permits the living trust to be treated as part of the estate, thus requiring only one Form 1041 filing. Beyond the reduction in the number of tax returns to be filed, the election provides many benefits, including the ability to hold S corporation stock (CPG, in this case) through its duration. It also permits the trust to use a fiscal year. Although estates are permitted a fiscal year, absent this election, trusts must use a calendar year.

Assuming K, as trustee of the living trust and estate representative, makes the Sec. 645 election, the combined filing could choose a calendar year or a fiscal year ending as late as Feb. 28, 2025. Of course, the joint federal individual income tax return will be due on April 15, 2024, unless extended (which is generally advisable, given the complexities of the final Form 1040, U.S. Individual Income Tax Return; the Form 706; and the initial Form 1041).

The Form 706 is due nine months after J’s date of death. The estate may request an extension of time to file for six months. As described below, the information required for the estate tax filing is extensive, and for this reason, estate tax filings are often extended. (Although beyond the scope of this column, an extension is also prudent because the filing of the Form 706 may change should K die before it is filed.)

This does not grant the estate an extension of time to pay the tax. The estate may request an extension of time to pay estate tax under Sec. 6161 for reasonable cause.

Information gathering

K must now proceed with the great information-gathering exercise. Every asset and liability must be reported on Form 706 with a description of the asset and an explanation of how it was valued. Note that the values reported on Form 706 will become the basis for the assets in the hands of J’s heirs, and that basis information must be reported on Form 8971, Information Regarding Beneficiaries Acquiring Property From a Decedent.

Subject to one caveat (the final bullet point below), because J’s estate is expected to be nontaxable, K cannot elect to use alternate valuation and needs to obtain only date-of-death values. You will carefully review each asset and liability with K and recommend that she obtain the following information:

- Financial statements, including the date of death, for the joint checking account, CD, brokerage account, and IRA. For accounts holding publicly traded securities, the broker should be able to provide a special securities valuation report. This report will list each security held, identification number, average high/low value, and accrued interest and dividend information.

- A business appraisal for CPG. To comply with the IRS requirements, K should hire a qualified appraiser to value the company and apply appropriate discounts to the interest.

- Form 712, Life Insurance Statement.

- Real estate appraisals by a qualified appraiser for each residence.

- For the HELOC, a statement reflecting the date-of-death balance, including accrued interest.

- A tangible personal property appraisal. Depending on the materiality of the value of these assets, K might consider an estimate of value. If she sells any items during the administrative period, she could use the sales price.

- With respect to the SLAT, consider assessing whether there is a risk of estate inclusion under Secs. 2036 and 2038. If the assets of the SLAT are determined to be includible in the estate, an estate tax liability may arise.

Attention to complex details needed

Although this example has provided an overview of estate administration, keep in mind that each administration involves numerous tasks and details that need careful evaluation. The process can vary significantly depending on the types of assets owned, their values, and the number of beneficiaries. The complexity is not always directly related to the asset value. The individual beneficiaries and their specific preferences can also add complexity, especially in cases of second marriages with children from both unions having different perspectives.

Losing a loved one can create significant stress on a family. A tax adviser plays a central role in keeping things moving for the family. Thus, it is essential to be prepared and organized as you navigate the process.

Contributors

Natalie M. Perry, CPA, J.D., is a partner with Harrison LLP in Chicago. Laura Hinson, CPA (North Carolina), is a managing director with Deloitte Tax LLP. Theodore J. Sarenski, CPA/PFS, CFP, is a wealth manager at SageView Advisory Group in Syracuse, N.Y. For more information about this article, contact thetaxadviser@aicpa.org.

Harrison LLP is responsible for the legal content of this article.

The Deloitte U.S. firms do not practice law or provide legal advice. Deloitte Tax LLP is responsible for the tax content of this article, which contains general information only, and Deloitte is not, by means of this article, rendering accounting, business, financial, investment, legal, tax, or other professional advice or services. This article is not a substitute for such professional advice or services, nor should it be used as a basis for any decision or action that may affect your business. Before making any decision or taking any action that may affect your business, you should consult a qualified professional adviser. Deloitte shall not be responsible for any loss sustained by any person who relies on this article.