- tax clinic

- FOREIGN INCOME & TAXPAYERS

Off the BEAT-en path: Planning opportunities

Related

Key international tax issues for individuals and businesses

IRS announces prop. regs. on international tax law provisions in OBBBA

QSBS gets a makeover: What tax pros need to know about Sec. 1202’s new look

Editor: Jeffrey N. Bilsky, CPA

The base-erosion and anti-abuse tax (BEAT) was introduced as part of the law known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, P.L. 115-97, in an effort to transition the U.S. tax system from a worldwide system to a quasi-territorial one.The BEAT is essentially a corporate minimum tax meant to prevent some multinational companies that operate in the United States from reducing their U.S. tax liability by shifting profits to low-tax jurisdictions.

While the BEAT has been part of the U.S. tax system for over six years, for some companies, BEAT planning opportunities had not been at the forefront until the company determined that it had a substantial BEAT liability.

This item provides an overview of the BEAT and explores potential planning opportunities for the tax. Moreover, it addresses the interplay of the BEAT with more recent provisions, such as the corporate alternative minimum tax (corporate AMT) and the Global anti–Base Erosion (GloBE) model rules under Pillar Two of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)/Group of 20 (G20) base-erosion and profit-shifting (BEPS) project addressing the tax challenges arising from the digitalization of the economy.

Overview

Under Sec. 59A, the BEAT is imposed on applicable taxpayers that make some base-erosion payments (e.g., interest, royalties, and payments for services) to foreign related parties. The BEAT is an additional tax separate from regular income tax. If the regular income tax liability is lower than the BEAT liability, the taxpayer must pay the regular income tax plus the amount by which the BEAT exceeds regular income tax. Currently, the BEAT applicable rate is 10%, with rates increasing to 12.5% for tax years beginning after Dec. 31, 2025 (Regs. Sec. 1.59A-5(c)).

An applicable taxpayer is a corporation that has (Sec. 59A(e)(1)):

- Average annual gross receipts of at least $500 million for the previous three tax years; and

- A base-erosion percentage for the tax year of 3% or more (2% for certain industries).

An applicable taxpayer does not include a regulated investment company, a real estate investment trust, or an S corporation. If the taxpayer is part of an aggregate group, then the determination of the average annual gross receipts and the base-erosion percentage is made at the aggregate group level. The aggregate group rules are beyond the scope of this item. However, note that special rules apply to partnerships that are part of the aggregate group.

Base-erosion payments

The Treasury regulations under Sec. 59A specify what items constitute base-erosion payments. Generally, payments reflected in cost of goods sold are treated as reductions in gross receipts rather than as deductions from gross income and are typically not considered base-erosion payments. Furthermore, some payments to foreign related parties are not considered base-erosion payments. This item discusses only payments for certain low-margin services mentioned under Regs. Sec. 1.59A-3(b)(3)(i). Such costs deducted for service payments made to foreign related parties that qualify for the services-cost method (SCM), a concept under U.S. transfer pricing rules, are specifically identified as an exception under the BEAT provisions. This means that such an amount is excluded from BEAT calculations, thus lowering a taxpayer’s potential BEAT liability.

BEAT mechanics

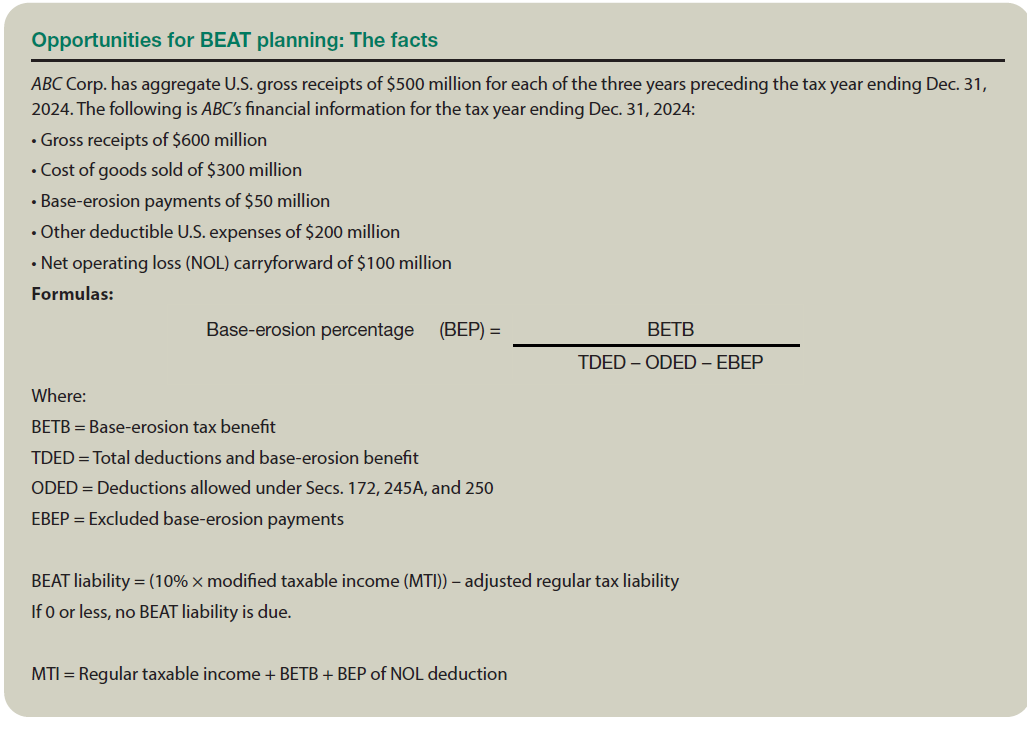

The following scenarios go through simplified examples of the mechanics to explore opportunities where BEAT planning can assist ABC Corp. with its overall tax liability. See first the tables “Opportunities for BEAT Planning: The Facts” and “Scenario 1: Base Case,” below.

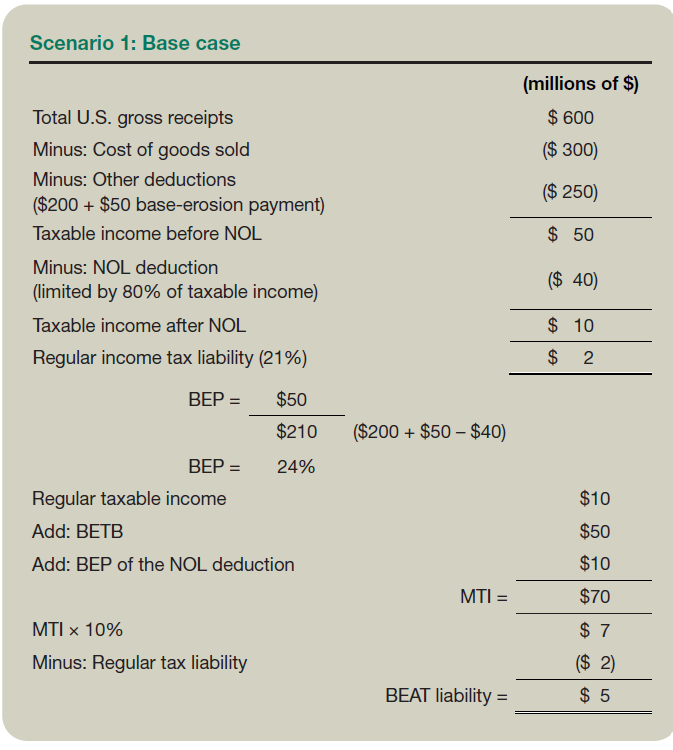

In Scenario 2 (see the table “Scenario 2: Base-Erosion Payments Are Capitalized Into Inventory,” below), by treating the base-erosion payments as part of inventoriable costs (i.e., cost of goods sold), the company was able to reduce its BEP to under 3%, allowing the company to be excluded from the definition of “applicable taxpayer,” resulting in no BEAT liability. Therefore, it is important to analyze which costs can be capitalized to inventoriable costs and included in cost of goods sold.

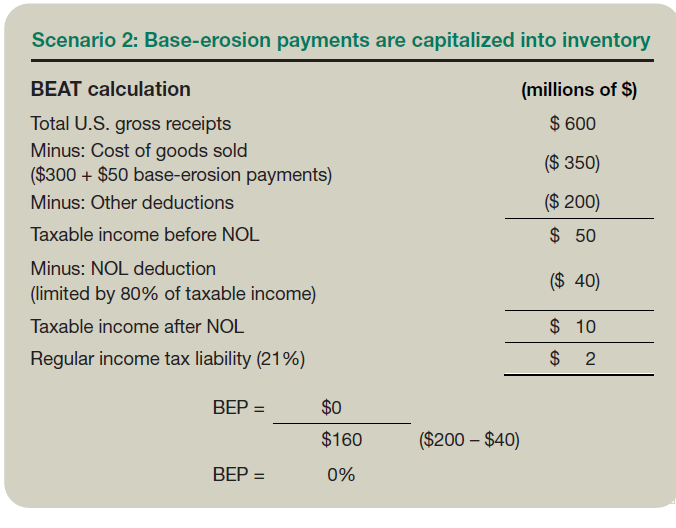

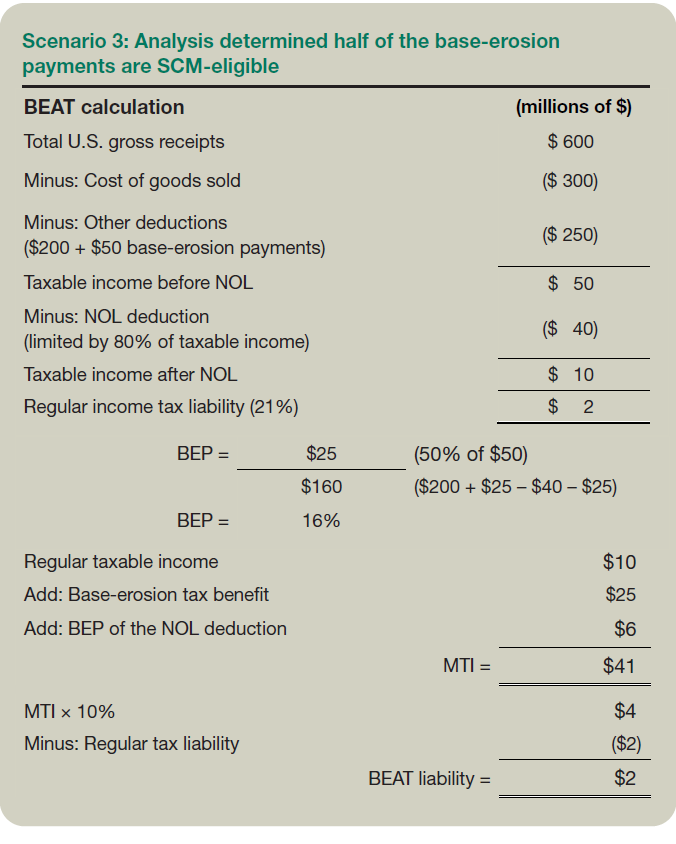

In Scenario 3 (see the table “Scenario 3: Analysis Determined Half of the Base-Erosion Payments Are SCM-Eligible,” below), by performing the SCM analysis, the company determined that half of the base-erosion payments were SCM-eligible and thus excluded for purposes of the BEAT. In this scenario, while the BEP was still over the 3% threshold, the BEAT liability was reduced by more than 50% from that in the base case (Scenario 1). Companies can explore whether the SCM aligns with their operations and can result in

The above discussion addressed two possible strategies to reduce the impact of the BEAT. Other potential strategies, such as strategic structuring of transactions, can also help reduce the base-erosion payments subject to the BEAT. Taxpayers may consider renegotiating the terms of intercompany agreements, exploring alternative financing structures, or optimizing supply chain arrangements. Using exemptions and safe-harbor provisions available under the BEAT rules can be a part of the planning process, providing relief for some types of payments.

Interplay of BEAT, corporate AMT, and Pillar Two

The BEAT and the corporate AMT are distinct U.S. tax provisions. As mentioned earlier, the BEAT focuses on preventing base erosion and profit shifting; the corporate AMT serves as a safeguard against large corporations paying minimal or no regular income tax. Pillar Two is part of the OECD’s and G20’s global tax framework that seeks to establish a global minimum tax to ensure multinational corporations pay a minimum level of tax on the income arising in each jurisdiction where they operate. The Pillar Two rules have not been adopted by the United States as of the writing of this item, and the specific rules regarding the corporate AMT and the Pillar Two provisions and when they may apply are beyond its scope.

Some multinational entities (MNEs) may find themselves subject to BEAT, corporate AMT, and Pillar Two provisions, resulting in complex tax implications. Specifically, the interplay between these taxes necessitates a thorough understanding of the mechanics of each set of provisions and how they may collectively affect a company’s total tax liability. Companies need to carefully navigate the distinct requirements of each provision while developing a unified approach to their global tax obligations.

Multinational corporations face challenges coordinating these provisions with their domestic and international tax planning strategies. Cross-border transactions, transfer pricing arrangements, and the timing and nature of such payments should be carefully reviewed to align with these provisions.

Planning and engagement

As companies grapple with the combined impact of these minimum tax provisions, strategic tax planning and proactive engagement are essential. With the uncertainty of the global tax landscape, it is important for companies to act now to partner with their inhouse and external tax teams to model tax-efficient scenarios to optimize their tax positions in a manner that is both legally sound and economically efficient.

Editor notes

Jeffrey N. Bilsky, CPA, is managing principal, National Tax Office, with BDO USA LLP in Atlanta. Contributors are members of or associated with BDO USA LLP. For additional information about these items, contact Bilsky at jbilsky@bdo.com.