- tax clinic

- ESTATES, TRUSTS & GIFTS

Wealth transfer strategies amid shifting interest rates

Related

Trust distributions in kind and the Sec. 643(e)(3) election

Estate of McKelvey highlights potential tax pitfalls of variable prepaid forward contracts

Recent developments in estate planning

Editor: Jeffrey N. Bilsky, CPA

In the early months of 2022, the Federal Reserve, challenged by inflation high above its 2% target rate, initiated what would become a series of swift, successive increases in the federal funds rate. These increases quickly brought the interest rate from near zero in March 2022 to a range of 5.25% to 5.50% by July 2023. For advisers, the size and the speed of the increase offer a reminder that interest rates — and the broader planning environment — are dynamic and ever-changing.

To best advise clients, practitioners must understand the effect of interest rates on wealth planning strategies. Given the long-term time horizon of most estate planning, this includes the effect of relevant interest rates at the time a strategy is implemented — and for many years into the future. Advisers and clients may hold differing views as to whether a given interest rate is “high” or “low,” as well as the thresholds at which such labels should be applied. After the 2008–2021 period of historically low interest rates, more recent rates indeed seem dramatically higher. However, if one looks back far enough in history and considers average rates over a longer term, the current rates begin to appear lower in comparison. Specific labels aside, advisers can deliver significant value by ensuring that proposed wealth transfer strategies fully consider interest rates.

The interest rates most relevant for tax purposes

Each month, the IRS publishes a revenue ruling that includes a set of interest rates known as the applicable federal rates (AFRs). Separate AFRs are provided for short-term (not over three years), midterm (over three but not over nine years), and long-term (over nine years) loans and instruments. Sec. 1274(d) and Regs. Sec. 1.1274-4(b) provide that AFRs are calculated monthly based on the yields of certain U.S. government obligations.

Historically, AFRs have been lower than the market rates traditional banks offer to customers. AFRs are important for a number of tax purposes, including as minimum rates for private loans (e.g., classifying certain loans as below-market and gift loans) and as part of many charitable contribution deduction and transfer tax calculations.

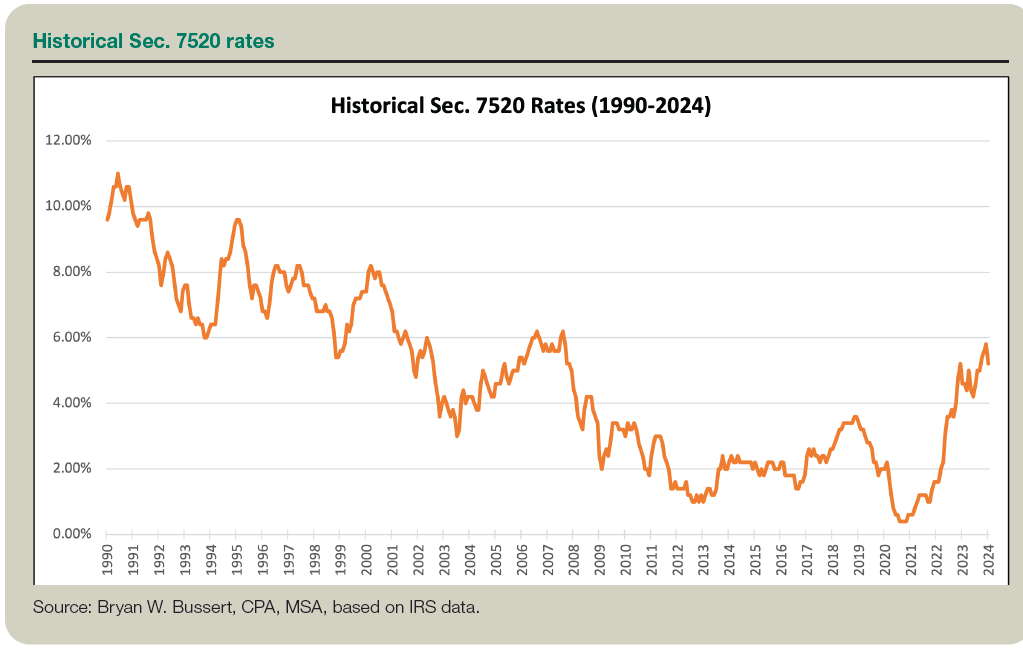

Each monthly AFR revenue ruling also includes the “Sec. 7520 rate” for the following month. In simple terms, Sec. 7520(a)(2) provides that the Sec. 7520 rate is 120% of the midterm AFR, with specific rounding. The Sec. 7520 rate is used as a discount rate and expected rate of return for many wealth transfer strategies. More specifically, the Sec. 7520 rate is critical to valuing certain annuities, life interests, and remainder or reversionary interests. In addition, practitioners must use the Sec. 7520 rate in calculating the value of certain charitable contribution deductions and valuing certain property for transfer tax purposes. The chart “Historical Sec. 7520 Rates,” below, illustrates their long-term trends.

Planners frequently refer to the Sec. 7520 rate as the “hurdle rate” in the context of wealth transfer planning. This term is appropriate insofar as the success of many strategies depends on an asset’s appreciating more (and/or producing investment returns greater) than this threshold rate.

Due to the IRS’s practice of announcing AFRs (and the Sec. 7520 rate) before month end, there is generally a week or more each month for advisers to help clients time transactions, such as trust funding, that are sensitive to interest rates. Advisers can also assist clients in selecting the most advantageous Sec. 7520 rate when the option of multiple rates is available. For example, Sec. 7520(a) allows a taxpayer to elect to use the Sec. 7520 rate for either of the two months preceding the month of the transfer if an income, estate, or gift tax charitable deduction is allowable for any part of the property transferred.

Planning in higher-interest-rate environments

If clients wish to give to qualified charities, a split-interest charitable remainder trust (CRT), such as a charitable remainder annuity trust (CRAT), is an effective estate planning tool amid higher interest rates. A CRAT is an irrevocable trust established to initially benefit a noncharitable beneficiary (often the grantor) for life or for a set term (up to 20 years). During the initial term, annuity payments are made to the noncharitable beneficiary; afterwards, the remainder will benefit a charitable organization. The grantor is entitled to an upfront income and gift tax deduction equal to the calculated value of the charitable remainder interest. The value of the charitable remainder increases as the Sec. 7520 rate increases.

In addition to offering estate planning benefits, CRATs are powerful income tax strategies. If the assets transferred to a CRAT are sold by the trustee, the trust does not pay federal income tax on its investment income. Instead, a portion of the income is allocated to the noncharitable beneficiaries in accordance with annuity payments, providing income tax deferral.

Clients may additionally consider establishing a separate irrevocable life insurance trust (ILIT) in conjunction with a CRT. Sometimes referred to as “wealth replacement trusts” when coupled with CRTs, properly designed and administered ILITs keep death benefits paid under ILIT-owned life insurance contracts outside a client’s gross estate and provide a mechanism to “replace” (for the client’s heirs) the value of CRT assets transferred to charity. As the grantor and noncharitable beneficiary of the CRT, the older-generation client can use CRT distributions to fund, by way of gifts, the premiums on an ILITowned life insurance policy, providing for younger-generation family members with great tax efficiency.

For clients with estate values likely to exceed their basic exclusion amount (BEA), a qualified personal residence trust (QPRT) is another effective strategy in higher-rate environments. To take advantage of a QPRT, the grantor creates an irrevocable trust and transfers to its trustee a residence or vacation home. The grantor retains the right to live in the property without payment of rent for a term of years. At the end of the term, the residence is transferred to the QPRT’s remainder beneficiaries. Assuming the grantor survives the term, they can transfer a property (and future appreciation) to the preferred beneficiaries and leverage a significant discount to the value of the property for gift tax purposes. All else being equal, a higher Sec. 7520 rate results in a larger present value of the grantor’s term interest and a smaller value of the beneficiaries’ remainder interest (subject to gift tax at the time the trust is funded).

Example 1: Assume a client is single, age 65, and owns a home valued at $800,000. She establishes and funds a 12-year QPRT with typical reversion provisions in January 2024 when the Sec. 7520 rate is 5.2%. The client’s retained interest would be valued at $465,128, resulting in a taxable gift in 2024 of $334,872.

Example 2: Alternatively, assume the same facts, except that the client transferred the residence to the QPRT in May 2021 when the Sec. 7520 rate was 1.2%. The 2021 transfer would have resulted in a $266,784 retained interest and a $533,216 taxable gift. If the home appreciates in value at 3% per year, the property would be worth more than $1.14 million upon the termination of the QPRT at the end of the 12-year term.

In both examples, the client realizes material estate and gift tax savings if she outlives the 12-year term, although the strategy is clearly more effective using the higher Sec. 7520 rate. Of course, there are nuances to the strategy, and care should be taken when considering a QPRT. After termination of the grantor’s retained interest in the property, the property is no longer eligible for a basis adjustment under Sec. 1014 upon the grantor’s death. Instead, the QPRT beneficiaries would retain the grantor’s adjusted tax basis and may realize a much larger gain upon a subsequent sale.

A grantor retained income trust (GRIT) is an irrevocable trust to which a grantor transfers property and retains an income interest for a term of years. The retained income interest is generally valued using the Sec. 7520 rate and is subtracted from the value of the transferred property to determine the remainder interest and the value of the gift. While GRITs can be highly effective, especially as interest rates tick up, the popularity of the strategy waned after the 1990 enactment of the Internal Revenue Code Chapter 14 special valuation rules, including Sec. 2702. In general, Sec. 2702 specifically assigns zero value to retained interests in trusts created for family members and, thus, significantly restricts the application of the GRIT strategy. To achieve the desired transfer tax benefits, the GRIT beneficiaries cannot include the grantor’s spouse, ancestors (or spouse’s ancestors), lineal descendants (or spouse’s lineal descendants), siblings, or a spouse of the aforementioned individuals. The extensiveness of this list, from Sec. 2704© (2), reveals why the GRIT strategy is less common today. However, clients seeking to make transfers to friends, certain extended family members (such as a nephew or niece), or an unmarried partner may find a GRIT to be the right tool.

From a broader perspective, higher interest rates serve as a drag on the economy, increasing costs and potentially causing businesses to pull back on capital investments and hiring and prompting consumers to reevaluate budgets and reduce spending. A consequence may be a decline in the value of certain public equities, real estate, and private businesses. Such declines provide opportunities to implement gifting strategies that use less of a client’s BEA, and lower asset values require less generation-skipping transfer (GST) exemption to achieve a zero inclusion ratio.

Planning in lower-interest-rate environments

Several strategies are most effective in a lower-rate environment. Perhaps the simplest is a private or intrafamily loan. In practice, a loan is made between a family member (or a trust) and another family member, trust, or closely held entity. Traditionally, the loan is made by a grandparent or parent to a younger-generation individual. The borrower may use the funds for a variety of purposes, including to purchase assets, make investments, or provide capital to a business. To the extent the borrower’s rate of return exceeds the interest rate on the promissory note, there is a clear financial benefit. Unless a loan is between a grantor and their grantor trust (or between two grantor trusts with the same grantor individual), the interest will be taxable income to the lender and, depending on the use of the loan and the Sec. 163(h) tracing rules, the borrower may or may not be able to deduct its interest expense.

When interest rates decline, an opportunity arises to refinance existing intrafamily notes using a lower AFR. Before acting, practitioners should consider whether the promissory note can be prepaid without penalty and whether the note was previously modified or replaced, as a history of refinancing the same note may give rise to gift tax consequences. To provide additional comfort and avoid an adverse gift tax result, some advisers suggest repaying the loan and making a new loan, if possible, or providing compensation to the lender in exchange for the lower rate, which may mean repaying some portion of the note’s principal or adjusting the note’s maturity or other terms.

Perhaps the most popular (and effective) strategy employed over the last 15 years is a grantor’s sale of property to a grantor trust. Traditionally, an individual will sell a valuable asset, such as an interest in a closely held business, to a trust treated as a grantor trust under Secs. 671–678. The grantor often makes a relatively small gift of cash or liquid assets to the trust and, after a period, will then sell a business interest (or other asset) to the trust in exchange for a promissory note. The technique provides many financial and tax benefits, including the transfer of an appreciating asset outside the grantor’s estate with great income, gift, and GST tax efficiency. If the asset value appreciates at a rate greater than the note’s AFR, this strategy produces powerful results for the family.

For some clients, a self-canceling installment note (SCIN) may be used to enhance the above strategy. A SCIN is a promissory note with special features, including a principal-cancellation feature generally triggered upon the death of the holder. SCINs offer advantages but introduce additional costs, considerations, and potential risk.

Another popular low-risk strategy in lower-interest-rate periods is the use of grantor retained annuity trusts (GRATs). The technique has the client create and fund an irrevocable trust, which will then make a series of annuity payments to the grantor over a term of years. The Sec. 7520 rate is used to determine the value of the GRAT remainder interest at the time the trust is funded. Careful planning goes into selecting the assets that will fund the GRAT; ideal assets are those with above-average volatility and a high likelihood of material appreciation. The trust remainder is often transferred to an irrevocable trust but may benefit a variety of beneficiaries, assuming the grantor outlives the annuity term.

To illustrate the impact of the Sec. 7520 rate on the GRAT strategy, we can review the results of the strategy using the same facts but varying the Sec. 7520 rate:

Example 3: A client creates a GRAT and transfers to the trust a portfolio of publicly traded stock. The stock is expected to grow annually at 8% and earn 1.5% income. The total fair market value of the stock at funding is $2 million, no valuation discounts are claimed, and the GRAT term is 10 years. Annuity payments specifically calculated to produce a near-zero taxable gift will be made annually at the end of each year. (See the table “Effect of Interest Rates on Annuity Calculations,” below.)

When considering a GRAT strategy (as well as QPRT and GRIT strategies), advisers must also consider the estate tax inclusion period (ETIP) under Sec. 2642(f). The ETIP rules limit allocation of GST exemption to the closure of the ETIP, and thus attention must be given to GST tax efficiency.

Charitable lead trusts are more effective when interest rates trend lower. With proper planning, the grantor can realize an income tax deduction for the charitable contribution portion of the transfer. During the initial term, distributions are made by the trust to a charitable organization. At the end of the term, the remaining assets are distributed to one or more noncharitable beneficiaries. As interest rates fall, the present value of a charitable lead annuity trust (CLAT) remainder interest (treated as a taxable gift) also falls, reducing the amount of the BEA used for the strategy. Separate from a charitable lead trust, a variation on the QPRT for charitably inclined clients is a gift of a remainder interest in a home to charity. A gift of such a remainder interest is more effective in a lower-interestrate environment.

Monitoring TCJA sunset and rates

With the planned sunset of many provisions of the law known as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), P.L. 115-97, on the near-term horizon, proactive estate planning continues to be an important exercise. As advisers work with clients to take advantage of historically large estate, gift, and GST tax exemptions, various wealth transfer planning strategies will be employed. To achieve the best outcomes, the advisory team must continue to monitor interest-rate policies and integrate changes in rates within approaches, strategies, and planning decisions.

Editor notes

Jeffrey N. Bilsky, CPA, is managing principal, National Tax Office, with BDO USA LLP in Atlanta. Contributors are members of or associated with BDO USA LLP. For additional information about these items, contact Bilsky at jbilsky@bdo.com.