- column

- CAMPUS TO CLIENTS

Choice-of-entity analysis with the TCJA sunset approaching

Related

Navigating safe-harbor rules for solar and wind Sec. 48E facilities

Businesses urge Treasury to destroy BOI data and finalize exemption

IRS generally eliminates 5% safe harbor for determining beginning of construction for wind and solar projects

Editor: Annette Nellen, Esq., CPA, CGMA

In late 2017, Congress passed and President Donald Trump signed P.L. 115-97, commonly referred to as the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA). Many provisions made permanent changes to the Internal Revenue Code, but the majority of individual tax adjustments were passed as temporary provisions, with a sunset scheduled for tax years beginning after Dec. 31, 2025. Following enactment of the TCJA, tax advisers prepared strategies for clients based on existing and expected law. Advisers and clients recognized there was the real possibility that these strategies would need adjustment if Congress did not act prior to the sunset date. While it is feasible that such action could occur before Dec. 31, 2025, it is prudent for tax advisers — and tax educators — to consider contingent strategies if in fact Congress does not act.

This column discusses some possible approaches for taxpayer advisers to consider in advising clients. It also describes pedagogical options and project examples for educators to consider in adapting courses to provide students with information about the pending sunset of the TCJA individual changes. Since many tax courses directly or indirectly address choice-of-entity situations, this column presents strategies and course project tools in that context.

Choice-of-entity analysis

Several of the fundamental concepts of individual, passthrough entity, and corporate taxation as applied to trade or business income are effectively demonstrated through a choice-of-tax- entity analysis. By comparing and contrasting the tax rules that apply to the different types of entities that can be used for trade or business activities and their owners, advisers and educators can drive home the variety of tax results that can occur across a similar set of economic facts and circumstances.

While explaining these ideas conceptually to clients and students provides a good tax knowledge baseline, developing deeper understanding and analytical skills about choice of tax entity is enhanced when real analytical models are used to compute hypothetical outcomes.

It is important to emphasize to both clients and students that a choice-of-entity analysis is not a one-and-done activity. Simply choosing a tax entity upon formation and never looking back may result in missed opportunities to maximize after-tax wealth. Changes in any of the following could result in a reevaluation of the current tax entity employed:

Federal, state, and local tax law, both major and minor (such as the return to prior law due to a sunset provision, as with the TCJA);

- Business and economic conditions;

- Demographics of the business owners;

- Succession planning; and

- Legal developments in the core business activity.

Differences in entity taxation of current income — current law

The most obvious differences between taxation of C corporation taxable income and taxation of income earned in other tax entities relate to marginal tax rates. The TCJA reduced C corporation tax rates to a flat 21% on taxable income. Congress made this rate reduction permanent, so it does not sunset on Dec. 31, 2025. Individual owners, however, are subject to graduated rates of tax as taxable income increases, with a maximum marginal rate of 37%. These individual rates are lower than the pre-TCJA rates, and, upon the TCJA’s sunset, these rates revert to the higher rates. While this is just one variable to consider, if tax professionals advised their clients to choose an entity based solely on this factor, an annual 16% savings in federal tax would probably cause them to have a lot more C corporations than currently.

There may also be differences in how certain income is recognized or certain deductions are computed, depending on the type of tax entity. Prominent examples include:

- The dividends-received deduction under Sec. 243 is available only to corporations;

- The $10,000 limitation on state and local taxes as itemized deductions under Sec. 164 applies only to individuals;

- The differences in taxable income or adjusted gross income limitations on the deduction for charitable contributions under Sec. 170;

- The qualified business income (QBI) deduction available for noncorporate trade or business income under Sec. 199A; and

- Additional non-income taxes that apply to the business income above and beyond regular income taxes in noncorporate entities, such as self-employment taxes and the additional Medicare tax imposed by Sec.

3101(b)(2) for sole proprietorships. Obviously, there are many other potential differences in treatment between tax entity alternatives, but these are the ones most likely to occur and are, thus, of major importance in this analysis.

Differences in tax treatment upon distribution of cash to owners as dividends or in liquidation

Although clients have varying interests in the intricacies of tax law related to taxable income, they are very attentive to the rules related to the tax consequences of cash distributions from a business. A major concern of most business owners is maximizing their after-tax cash flow from the business activity.

Selecting C corporation status creates a significant reality — double taxation of both the current business income and the potential gains from future disposition of the business assets or entire business. Dividends are not deductible to the corporation, and, therefore, shareholders must pay tax on dividends they receive that arise from income that was already taxed at the corporate level. In addition to income tax on these dividends, the shareholders may also incur the net investment income tax imposed by Sec. 1411 if that income exceeds certain thresholds. However, these consequences generally would not occur when owners extract cash from profitable entities outside a C corporation structure in the form of distributions.

The double taxation result is also a potential hurdle when the C corporation business is disposed of in an asset sale or deemed asset sale transaction, since the corporation would pay tax on any taxable gain from the sale of its assets, and shareholders would pay tax again on any cash they receive as either dividends or liquidating distributions. Although the owners may have no immediate plans to dispose of the business or its assets, situations can change rapidly as business conditions change, so this potential for double taxation relative to both current dividends and liquidating distributions must be considered when comparing entities. The after-tax cash flows from a business disposition that is remotely likely may nonetheless be estimated and adjusted in the present-value analysis of the transaction.

If the trade or business activity is sold in a stock transaction, any gain recognized in liquidation of C corporation stock would be subject to the net investment income tax imposed by Sec. 1411, just as dividends from C corporations would be during the years that the C corporation was operating the trade or business. Gain or loss on the disposal of an equity interest (i.e., stock or partnership units) in a passthrough entity is generally not subject to the net investment income tax if the individual owner is considered a material participant in the trade or business. Also, the computation of basis is different for C corporation stock than for passthrough entities, where partnerships and S corporations each have their own specific provisions that govern determination of basis in the ownership interest.

Choice-of-entity analytical tools for academic use

Many factors, both tax and nontax, must be considered in selecting the form of a tax entity for a closely held business. The nontax factors generally do not lend themselves to numeric analysis and modeling, but, clearly, the tax factors can be considered in quantitative terms.

One of the authors was in tax practice when the TCJA was enacted and participated in the firm’s efforts in developing tools to analyze the tax law changes and their effects on the firm’s closely held business clients. Those professional practice tools were practical illustrations that helped clients understand how the TCJA would affect their investments and in making tax entity decisions in reaction to the new law. We expected that these tools also would be helpful in teaching students not only the technical rules of the new law but also in applying those rules in hypothetical settings.

We have adapted the professional analysis templates for academic use. We applied the tools in the fall 2023 entity taxation creating a choice-of-entity case problem that incorporated the Excel tool and required students (formed into groups) to consider various scenarios regarding income growth, tax law changes, intergenerational transfers of the business, and others. The Excel workbook was editable, thus allowing students to adjust its core assumptions for a variety of changed conditions. Since the imminence of the sunset is upon us, we specifically lengthened the time horizon to include the transition in 2026 if Congress allows the sunset to occur. The principal deliverable was to provide the hypothetical client with written advice on:

- Retaining or changing the existing tax entity choice;

- Compensation decisions;

- Lifetime versus testamentary gifts;

- Ensuring the continuation of the business model and ethos; and

- Consideration of transfers of the business to non–family members.

After discussion and assessment, with some modifications, we again implemented the choice-of-entity case in the fall 2024 entity taxation course. The following is a description of the initial use of the tool in tax practice and the impact generally of the sunset.

Comparisons under current tax law

An after-tax cash flow analysis of the TCJA comparing an S corporation with a C corporation can be demonstrated using some simple assumptions.Although we did not compare the two corporate structures to a partnership structure, it would be relatively simple to adapt the worksheet to do so. We did this analysis in an Excel template constructed specifically for such comparisons and used the following assumptions:

- Trade or business income (before state income taxes) is $1 million annually for 10 years;

- No capital expenditures are anticipated;

- Trade or business income is earned in a state with a 5% state income tax rate;

- 100% of trade or business income is QBI (i.e., not subject to any limitation for a specified service trade or business, or due to limitations of W-2 wages or unadjusted basis immediately after acquisition of qualified property);

- There is only one shareholder who materially participates in the business, with an initial capital contribution of $10,000;

- The trade or business will be sold in an asset sale transaction at the end of 10 years for $5 million, allocated entirely to created goodwill; and

- A 5% discount rate is applied to determine the net present value (NPV) of after-tax cash flows over the 10-year period.

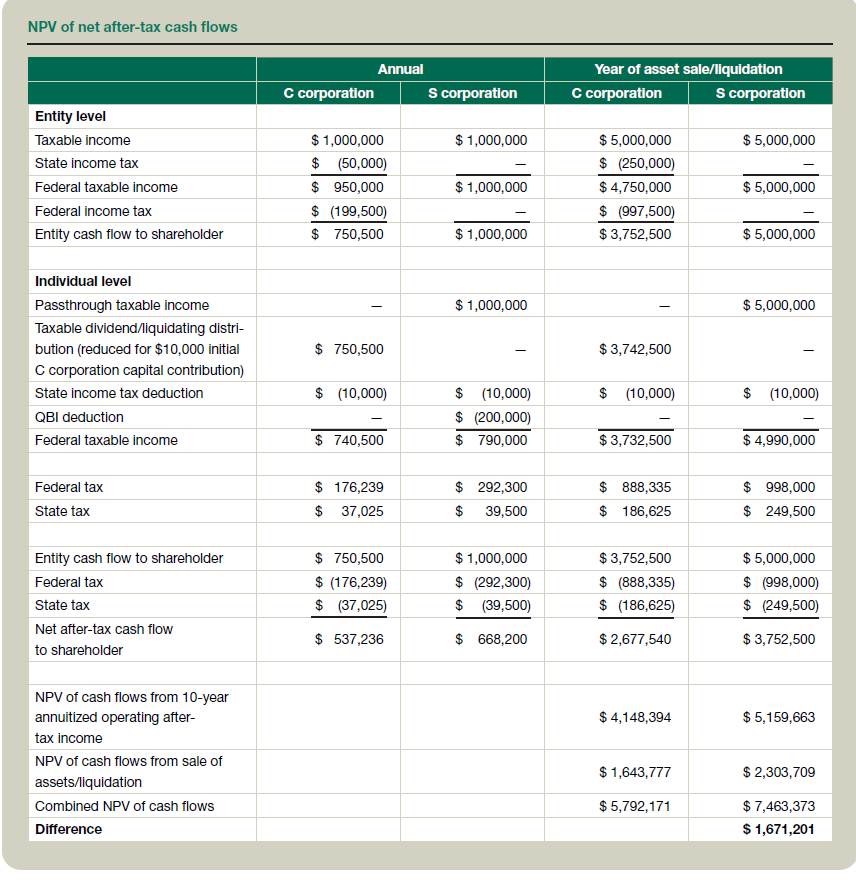

The excerpt of the Excel worksheet in the table “NPV of Net After-Tax Cash Flows” shows the computation of cash flows to the individual shareholder over the 10-year period under current law.

Again, under current law, there is a material advantage to after-tax cash flows to the shareholder if he or she chose an S corporation structure versus a C corporation structure for the operating business. Based on these computations and using the discount rate assumed, our hypothetical client would have more than $1 million in additional net after-tax cash flows if an S corporation entity was used.

But here comes the TCJA sunset …

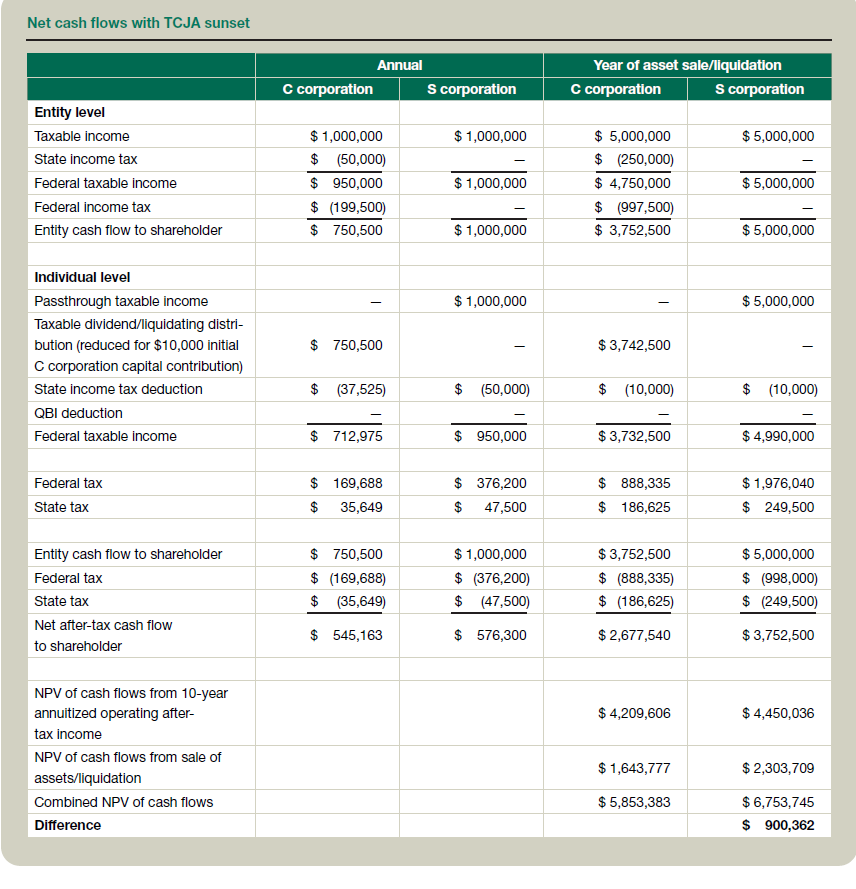

Although there are many collateral impacts on individual federal income taxation from the potential TCJA sunset, perhaps the most pressing for closely held business owners are the expiration of the state and local tax (SALT) deduction limitation, the expiration of the QBI deduction, and the reversion to pre-TCJA marginal rates. Such changes could have a significant impact on the results of the computations performed above, using the same assumptions previously explained.

Note that many states have enacted changes to state tax rules to insulate the effects of the $10,000 SALT cap in some settings. Generally called the passthrough entity tax (PTET), these provisions were approved by the IRS in Notice 2020-75. For state taxes properly paid by the flowthrough entity, the states either allow the owners to claim a state income tax credit for some or all of the taxes paid or require that the owner exclude the passthrough income when calculating state taxable income. The schedules below do not include the impacts of a state-level PTET, but, of course, in practice, this should be done. See the table “Net Cash Flows With TCJA Sunset” for a look at how the analysis changes when these sunsetting provisions are accounted for.

Simply eliminating the impact of the state and local tax deduction limitation and the QBI deduction and reflecting the reversion of the top marginal individual rate back to its pre-TCJA level of 39.6% narrows the advantage of selecting an S corporation considerably when viewed through this scope. If there were other nontax reasons that might make a C corporation structure desirable to our hypothetical client, seeing this analysis might tip the scales in favor of choosing that option.

So what should advisers and educators do?

Of course, net after-tax cash flows are but one way to analyze the appropriateness of different tax entity selection options to apply to operating businesses, but this methodology is often one of the most effective and meaningful when used to demonstrate the impact on cash flows to clients. In addition to this type of numerical analysis, tax professionals must also ensure that they are discussing other potential impacts that can occur as a result of selecting one entity type over another. These can include reasonable-compensation issues, retirement and other benefit plan participation, liability exposure, regulatory or contractual issues, and myriad other nontax concerns.

However, individuals in the ownership group are often driven by the impact a business choice makes on their personal wealth, and the analysis described above is a concrete, easily explained way to quantify the impact of one of the fundamental decisions necessary for any business. Planning for the unknown of whether any of the expiring provisions will be extended offers a real-life example for students of something practitioners and corporate tax department personnel must deal with. Asking students how they would prepare clients for upcoming changes to Form W-4, Employee’s Withholding Certificate; estimated taxes; re-cordkeeping; and more is a good exercise for future tax practitioners.

Monitoring for change

At the time of this writing (two months before the 2024 election), the U.S. political landscape is, as is usually the case in an election year, fluid and unpredictable. Control of Congress and the presidency could shift. Regardless of those potential realities, what is clear is that the current Code mandates a reversion to pre-TCJA provisions for tax years beginning after Dec. 31, 2025. In the year leading up to that date, practitioners and academics will need to carefully monitor these developments in advising their clients and educating their students.

Contributors

Thomas J. Purcell III, CPA, J.D., Ph.D., is a professor emeritus in the Department of Accounting, and Deyna C. Rouse, CPA, MST, is an instructor in the Heider College of Business, both at Creighton University in Omaha, Neb. Annette Nellen, Esq., CPA, CGMA, is a professor in the Department of Accounting and Finance at San José State University in San José, Calif., and is a past chair of the AICPA Tax Executive Committee. For more information about this column, contact thetaxadviser@aicpa.org.