- column

- CASE STUDY

Tax strategies for cash and cash equivalents

Related

Supercharging retirement: Tax benefits and planning opportunities with cash balance plans

Revisiting Sec. 1202: Strategic planning after the 2025 OBBBA expansion

Planning to preserve assets while providing long-term-care options

Editor: Patrick L. Young, CPA

An investor’s cash reserves are typically invested in short-term, highly liquid investments. These investments are often referred to as cash and cash equivalents and may take the form of money market accounts, certificates of deposit (CDs), or Treasury bills. Money market accounts may be either taxable or tax-exempt, so taxpayers must compare after-tax yields when analyzing these investments. Note that some federally tax-exempt money market mutual funds avoid the alternative minimum tax in addition to regular taxation.

With short-term cash investments, taxpayers typically report interest income currently (i.e., as earned). However, interest income from CDs maturing in one year or less and Treasury bills is recognized when these investments mature, which enables taxpayers to defer income recognition from one year to another (Secs. 1272(a) (2)(C) and 454(b)). For some investors, this may be a factor when making investment decisions.

Note: The SEC requires certain money market funds to price shares in a manner that more accurately reflects the market value of their underlying portfolios rather than a stable $1 per share. A taxpayer who makes frequent purchases and redemptions of these “floating net asset value (NAV)” money market funds could experience a high volume of small gains and losses, making tax compliance burdensome. In response, the IRS issued guidance providing a simplified, aggregate annual method of tax accounting for gains and losses in these floating NAV funds. Specifically, the regulations permit shareholders to measure net gain or net loss without transaction-by- transaction calculations. In addition, the final regulations expand the availability of the simplified method to all money market funds (Regs. Sec. 1.446-7). See Section 15.16 of Rev. Proc. 2024-23 for guidance on how to change to or from this simplified NAV method of accounting.

Choosing between taxable and tax-exempt investments

Comparing taxable and tax-exempt returns

An investor often evaluates investment alternatives in terms of after-tax return. The practitioner may be asked to assist the taxpayer in deciding between a taxable investment (such as U.S. Treasury bills or CDs) and a tax-exempt instrument. Depending on the investor’s tax bracket and state tax consequences, the difference on the return between taxable and tax-exempt investments can be significant. For tax-exempt investing, a taxpayer can invest in municipal bonds, tax-free money market accounts, or mutual funds investing only in municipal bonds. Some funds invest only in tax-exempt bonds of a specific state so residents of that state who invest in that fund avoid state income tax on the earnings as well (i.e., states generally do not tax residents on interest earned on bonds issued by that state).

Municipal bonds usually carry a lower stated interest rate than taxable bonds of similar quality and safety. However, much of the appeal of investing in municipal bonds is that, depending on the investor’s tax rate, the after-tax yield from these bonds can exceed the after-tax yield from a bond that pays a higher rate of taxable interest.

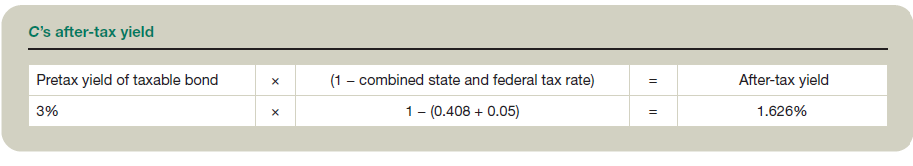

Example 1. Comparing yields on taxable and tax-exempt investments: C is considering investing in either a AAA-rated insured tax-exempt bond paying interest of 2% or a corporate bond producing taxable interest of 3%. She wants to know which bond produces the larger after-tax yield. She is in the 40.8% (37% + 3.8% net investment income tax) federal tax bracket, and her state tax rate is 5%. However, C’s state does not tax the tax-exempt bond interest. C does not itemize deductions on her federal return.

The interest on the tax-exempt bond has already been stated in terms of an after-tax yield of 2%. However, the after-tax yield of the corporate bond can be determined using the formula shown in “C’s After-Tax Yield.”

Because the after-tax yield of the AAA-rated insured tax-exempt bond (2%) is greater than the after-tax yield of the corporate bond (1.626%), the tax-exempt bond appears to be the better investment.

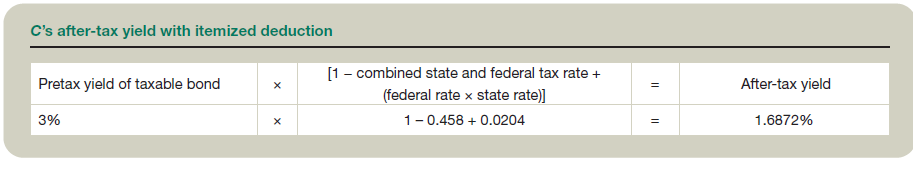

Variation: If (1) the taxable interest is subject to state income tax; and (2) state taxes are deductible on C’s federal tax return (as an itemized deduction) if she chooses to itemize deductions, the formula would be as shown in “C’s After-Tax Yield With Itemized Deduction.”

Here, the tax-exempt bond still yields the greater after-tax return, even though C is allowed to deduct the state income taxes (subject to the $10,000 annual limitation on state and local taxes) paid on the taxable interest on her federal return.

While interest on tax-exempt bonds is not subject to federal income tax, gains and losses on the sale of a tax-exempt bond are recognized. Thus, the tax effect of disposing of a tax-exempt bond prior to maturity should be considered. Controlling the timing of such gains or losses is easier when bonds are individually held versus through a mutual fund. Investors in tax-exempt bond mutual funds recognize gains passing through from the fund or, in some cases, when they dispose of their shares in the mutual fund.

Other factors to consider

Other factors in addition to state and federal marginal tax rates can affect the analysis of taxable versus tax-exempt investments. These include:

- Taxable or tax-exempt income can indirectly affect a taxpayer’s tax liability because of the effect the income has on other tax items. For example, taxable interest income increases adjusted gross income (AGI), which can reduce certain credits, deductions, and exemptions subject to an AGI-based phaseout.

- For taxpayers receiving Social Security benefits, tax-exempt interest is included in their provisional income, which is used to determine the taxable amount of such benefits. Thus, tax-exempt interest can impact the tax liability of Social Security recipients, particularly for those whose provisional income is at or near the base amounts used for computing taxable Social Security benefits (e.g., $25,000 for single taxpayers and $32,000 for taxpayers filing jointly). However, the impact may be less than if the taxpayer invested in taxable accounts, since the amount of tax-exempt income would generally be smaller.

- Taxpayers who do not generate sufficient taxable income may lose the benefit of their itemized or standard deductions and certain credits related to dependents. Thus, taxpayers will generally want to generate enough taxable income to benefit from these deductions or credits, assuming the rate they earn on taxable investments exceeds that on tax-free investments.

Tax advantages of Treasury bills

Treasury bills (sometimes referred to as T-bills) are money market securities that represent short-term government financing, with maturities ranging from a few days to 52 weeks. Periodic interest is not paid on Treasury bills; instead, they are sold at a discount and mature at face value. Treasury bills are ideal for investors who want safety and liquidity. Treasury bills can be purchased through banks and brokerage firms or directly from Treasury at TreasuryDirect. Alternatively, investments in Treasury bills can be made through mutual funds that specifically invest in short-term debt instruments.

The original-issue-discount (OID) rules of Sec. 1272 generally control the timing of income recognition for certain instruments issued at a discount. Sec. 1272 requires that OID be treated as interest income over the life of the obligation rather than when the instrument matures. However, these rules do not apply to short-term obligations (i.e., those with fixed maturity dates not more than one year from the date of issue, such as short-term CDs and Treasury bills); instead, their income is taxable at maturity (or sale date, if earlier) (Secs. 1272(a)(2)(C) and 454(b)). Thus, the obvious planning technique is to acquire a short-term debt instrument that matures in the following (as opposed to the current) tax year, to defer income recognition for a year. However, this planning technique may not be appropriate if the taxpayer expects to be in a higher tax bracket in the following year.

Treasury issues several types of debt instruments that individual investors can purchase (either individually or through mutual funds). It is important to understand the difference between these instruments, as the rules for taxation of them differs. Common Treasury debt instruments include:

Treasury bills: As discussed above, these instruments are issued at a discount and mature in 12 months or less.

Treasury notes: These are medium-term instruments (terms ranging from two to 10 years) that pay interest semiannually. Interest is taxable when received (or constructively received), and these notes may be purchased at a discount or premium, depending on market conditions when acquired.

Treasury bonds: These bonds are like Treasury notes except they have longer maturities (generally, 30 years). These are taxed to holders in the same manner as Treasury notes.

Treasury separate trading of registered interest and principal of securities (STRIPS): These are Treasury notes and bonds that have been stripped of their interest coupons.Thus, they are sold at a discount, and the holder receives the principal when the debt matures.Treasury STRIPS are zero-coupon instruments because holders do not receive periodic interest payments.Investors recognize income on these bonds under the OID rules.

Treasury inflation-protection securities (TIPS): These are bonds that both pay interest semiannually and pay investors for inflation adjustments to the bond’s principal.

Floating-rate notes (FRNs): FRNs are issued for a term of two years and pay interest quarterly. They may be issued at, below, or above the security’s face value. Interest payments on an FRN vary based on discount rates for 13- week Treasury bills.

U.S. savings bonds: Series EE savings bonds are sold electronically at TreasuryDirect. Paper EE bonds were issued at a discount (one-half of face value) prior to Jan. 1, 2012. Electronic form Series EE savings bonds are issued at face value in amounts of $25 or more. Series I bonds are inflation-indexed bonds issued at face value. The interest, which is added to the bond monthly, is paid when the bond is redeemed.

A taxpayer who holds a Treasury bill to maturity recognizes no capital gain or loss. Instead, proceeds in excess of basis (i.e., the acquisition discount amount) are taxed as ordinary income because they are considered a recovery of discount or interest income.

An election is available under Sec. 1282(b)(2) to recognize the acquisition discount over the bond’s life rather than at maturity or sale.The acquisition discount is measured by the difference between the stated redemption price at maturity and the cost of the Treasury bill. The discount is accrued using the ratable accrual method. The election is made by attaching an election statement to the taxpayer’s return and, once made, applies to all short-term obligations (as defined in Sec. 1283(a)(1)) acquired by the taxpayer on or after the first day of the first tax year to which the election applies. It then applies to the tax year for which the election was made and all subsequent tax years, unless the IRS agrees to revoke the election at the request of the taxpayer.

This election could be beneficial to a taxpayer who needs to accelerate income to use expiring loss carryforwards or anticipates higher income tax rates in the future. However, the long-term consequences of the election should be considered. A one-year tax advantage may turn into a long-term tax detriment.

Taxpayers who have elected to recognize the acquisition discount over the obligation’s life can elect to compute the daily portion of the discount using the constant yield method (Sec. 1283(b)(2)). However, the complexity of the computation makes this election useful only in limited circumstances.

State and local governments cannot tax interest income from Treasury bills (31 U.S.C. §3124). This can be beneficial for taxpayers who are subject to state and local income taxes.

If a Treasury bill is sold before maturity, any amount received in excess of tax basis is taxed as ordinary income to the extent it represents a recovery of the acquisition discount (Sec. 1271(a)(3)). Proceeds in excess of the recovered discount are taxed as short-term capital gain because Treasury bills are capital assets (Sec. 1221).

Example 2. Computing gain on Treasury bill sold prior to maturity: G purchased a six-month, $10,000 Treasury bill for $9,900 on Sept. 1 of year 1. She sold the bill (before maturity) on Jan. 22 of year 2, for $9,950. G did not elect to accrue the $50 acquisition discount prior to maturity.

G realized a $50 gain on the sale ($9,950 proceeds less $9,900 cost) in year 2. Of that amount, G reports $40 as interest income ($50 discount ÷ 181 days to maturity × 144 days held) and the remaining $10 ($50 – $40) as short-term capital gain.

Note: If G had elected under Sec. 1282(b)(2) to include the discount in income ratably, the income recognized would be added to the basis of the Treasury bill to calculate gain or loss (Sec. 1283(d)(1)). Thus, her capital gain on disposal would still be $10. However, $34 ($40 × 122 ÷ 144) of the interest income would be reported in year 1, since she held the bond for 122 days that year, and $6 ($40 × 22 ÷ 144) would be reported in year 2.

The sale of a Treasury bill will result in a capital loss only if the sales proceeds are less than the taxpayer’s basis (i.e., cost, unless an election has been made to accrue discount into income). If no accrual election has been made and gain from a sale is less than the amount of discount that would have ratably accrued to the date of sale, the only income reported is ordinary income for the amount of the gain (i.e., ordinary income is recognized based on the lesser of gain from the sale or the amount of discount that would have ratably accrued to the date of sale) (Sec. 1271(a)(3)).

Contributor

Patrick L. Young, CPA, is an executive editor with Thomson Reuters Checkpoint. For more information about this column, contact thetaxadviser@aicpa.org.

This case study has been adapted from Checkpoint Tax Planning and Advisory Guide’s Individual Tax Planning topic. Published by Thomson Reuters, Frisco, Texas, 2024 (800-431-9025; thomsonreuters.com).