- tax clinic

- corporations & shareholders

Exposing the hidden disqualified individuals of Sec. 280G

Related

Businesses urge Treasury to destroy BOI data and finalize exemption

IRS generally eliminates 5% safe harbor for determining beginning of construction for wind and solar projects

Deducting corporate charitable contributions

Editor: Michael Wronsky, CPA, MST

In the labyrinth of due diligence that precedes the sale of a C corporation, Sec. 280G often emerges as an unanticipated complexity, akin to a hidden trap for the unwary. This section can ensnare unsuspecting executives as they near the transaction’s culmination. If not navigated with care, it can lead to costly delays at the 11th hour. Central to this challenge is the identification of disqualified individuals (DQIs) to whom it applies, a task deceptively simple in theory, yet laden with subtleties that can undermine the entire process.

This item shines a light on the rules for DQIs within Secs. 280G and 4999, offering help to ensure a thorough and complete analysis that stands up to buyer scrutiny and that safeguards those potentially exposed to these punitive provisions.

While multiple areas of complexity can arise under Sec. 280G, this item focuses on the concept of DQIs. The determination of who is a DQI is foundational for a Sec. 280G analysis, yet DQIs can be overlooked due to complicated rules, potentially creating exposure due to an incomplete Sec. 280G analysis.

Sec. 280G background

Sec. 280G, enacted in 1984, was intended to curb the perceived abuse of excessive compensation paid to executives and other key employees in connection with corporate changes in control. The section applies to payments contingent on a change in control of a C corporation, which Sec. 280G calls “parachute payments.” If the aggregate value of parachute payments made to a DQI exceeds three times the DQI’s base amount (their average compensation over a specific prior-year period, generally called their “280G safe harbor”), then there is a potential Sec. 280G exposure on the amount of aggregate parachute payments exceeding the DQI’s base amount. These excess amounts are known as “excess parachute payments,” which are potentially nondeductible by the corporation and subject to a 20% excise tax under Sec. 4999, which is imposed on the DQI and is subject to withholding.

DQIs consist of employees and independent contractors who provided services to the company within the 12-month period prior to and ending on the date of the change in control and include:

- An officer;

- A shareholder who owns more than 1% (by value) of the company’s stock (including stock underlying vested options held by the individual and stock owned by related persons); or

- A highly compensated individual (the highest-paid 1% of employees (or, if fewer, the highest-paid 250 employees) during the 12-month period prior to and ending on the date of the change in control).

While these requirements appear straightforward, there are nuances. Careful and early consideration is necessary to identify the DQIs and the existence of excess parachute payments, primarily to take advantage of an exception to Secs. 280G and 4999. Non–publicly traded companies are afforded an opportunity to cleanse Sec. 280G exposure via a shareholder vote by receiving greater than 75% approval from all shareholders entitled to vote, emphasizing the importance of capturing all DQIs. This importance is further compounded by the scrutiny placed on Sec. 280G by buy-side due diligence teams, who generally apply an “abundance of caution” approach and could delay the close of the transaction if major issues are discovered.

Therefore, a thorough review is needed, and it may be recommended to treat certain individuals of non–publicly traded companies as DQIs even if their inclusion in the analysis is not clearly required. It is critical that this review take place as early as possible during negotiations to avoid costly delays to the closing process. Accordingly, five areas to consider when determining DQIs are Sec. 318 attribution, subjectively defined officers, members of the board of directors, former service providers, and U.S. employees of foreign employers.

Sec. 318 attribution

One of the categories of potential DQIs that is generally overlooked is the application of the Sec. 318 attribution rules. These rules are used to determine the stock ownership of a DQI for purposes of the greater-than-1%-shareholder requirement. The rules generally attribute the ownership of stock from one person or entity to another, based on certain family or business relationships. For example, the rules attribute the ownership of stock from a parent to a child, from a trust to a beneficiary, from a partnership to a partner, and from a single-member limited liability company (SMLLC) to its owner.

The attribution rules can result in some individuals being considered DQIs even though they do not directly own any stock of the corporation. For instance, an employee who is a beneficiary of a trust that owns more than 1% of the stock of the corporation may be a DQI by attribution. Similarly, an employee who is the owner of an SMLLC that owns more than 1% of the stock of the corporation is a DQI by attribution. It is also common for owners of closely held corporations to employ their children. If the parent is a greater-than-1% shareholder, their employee child is considered a DQI.

Subjectively defined officers

The determination of who is an officer is another potential pitfall, as the scope of inclusion is subjective and not limited simply to C-suite executives. Regs. Sec. 1.280G-1, Q&A 18(a), provides that an officer: is determined on the basis of all the facts and circumstances in the particular case (such as the source of the individual’s authority, the term for which the individual is elected or appointed, and the nature and extent of the individual’s duties). Any individual who has the title of officer is presumed to be an officer unless the facts and circumstances demonstrate that the individual does not have the authority of an officer. However, an individual who does not have the title of officer may nevertheless be considered an officer if the facts and circumstances demonstrate that the individual has the authority of an officer. Generally, the term officer means an administrative executive who is in regular and continued service. The term officer implies continuity of service and excludes those employed for a special and single transaction.

Further complexity arises with affiliated groups. Consider an organization consisting of a partnership parent and a C corporation subsidiary. While it is generally considered that Sec. 280G does not apply to partnerships, because there is a C corporation in the affiliated group, Sec. 280G may nevertheless apply. Employers often believe that the application of Sec. 280G is limited to officers employed by the C corporation, erroneously excluding officers at the parent level that are receiving significant transaction-related compensation. Employers must carefully consider whether these officers should be considered DQIs, and, in the authors’ experience, they generally are.

Members of the board of directors

Service providers often flying under the radar are members of the board of directors. What is particularly frightening about failing to include directors that should be considered DQIs is that, while their compensation (and resulting base amount) is generally insignificant, they often receive substantial transaction-related payments, causing them to have significant Sec. 280G exposure. Now, directors are not DQIs solely as a result of being directors — that only satisfies the requirement of being a service provider. They must still also meet one of the other three criteria (usually, an officer or greater-than-1% shareholder).

So, when are directors considered officers? Factors to consider may include whether the director had the authority to exercise a significant amount of the administrative and policymaking functions of the corporation, having a title or a position indicating officer status, and whether the director participated in the corporation’s management or operations. Again, in the authors’ experience, directors are commonly treated as officers for DQI determination where cleansing is afforded.

Former service providers

DQIs include those who rendered services during the “disqualified individual determination period,” meaning the 12-month period ending on the date of the change in control (Regs. Sec. 1.280G-1, Q&As 15 and 20). This seems simple enough until one considers that this includes former service providers. For example, a service provider who resigns, retires, or is terminated from the corporation within the 12-month period prior to and ending on the date of the change in control is a DQI if the employee at any time during the 12-month period was an officer, a shareholder who owned more than 1% of the stock, or a highly compensated individual.

Now, it certainly is possible that a former service provider has little or no compensation that would be considered parachute payments, but this does not preclude them from being considered a DQI. Further, it is not uncommon for former employees to retain vested rights that would provide for compensation upon a sale (e.g., a vested phantom stock agreement payable upon a change in control) or to have received payments that would be presumed parachute payments under Sec. 280G.

US employees of foreign employers

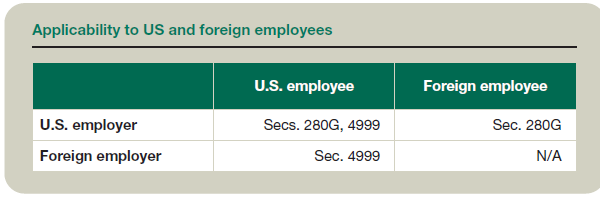

Another scenario where determination of DQIs can be overlooked is when dealing with foreign entities that have U.S. employees (via either citizenship or residency). Sec. 280G is not necessarily well known among business owners and executives in the United States, let alone internationally, so it should come as no surprise that it and Sec. 4999 are often overlooked by employers and buyers that are not engaged in a trade or business within the United States. The table “Applicability to US and Foreign Employees,” below, provides a simple snapshot of when the two provisions may apply.

A concerning situation can arise where a foreign employer has U.S. employees. Although the foreign employer may not be subject to the provisions of Sec. 280G, a U.S. employee who is considered a DQI must still comply with Sec. 4999. As a foreign employer and/or buyer may be unaware of Sec. 280G and the excise tax exposure to its DQIs, the cleansing vote may not be obtained, and the U.S. individual(s) are now fully exposed to an inescapable 20% excise tax on a potentially significant sum of excess parachute payments.

Importance of planning

This is not an exhaustive list of considerations relating to Sec. 280G and determination of DQIs, but, hopefully, it highlights the importance of a thorough review and provides direction on some areas that need additional scrutiny. For non–publicly traded companies relying on the cleansing vote, it is generally recommended to take a worst-case-scenario approach and include individuals who might be considered DQIs even if questions remain. Of course, there are reasons to exclude individuals, such as risk associated with having to sign waivers and failing to obtain shareholder approval, as well as concerns of optics relating to the adequate-disclosure rules. If Sec. 280G is a potential concern, it is best to start planning well in advance.

Editor Notes

Michael Wronsky, CPA, MST, is managing director of Baker Tilly’s Washington Tax Council.

For additional information about these items, contact Wronsky at michael.wronsky@bakertilly.com.

Contributors are members of or associated with Baker Tilly US, LLP.