- feature

- GAINS & LOSSES

The time value of capital losses

Capital gains in the forecast? Stockpiling losses may make sense. For certain investors, systematically harvesting capital losses in a portfolio in anticipation of future capital gains can be a beneficial strategy, significantly increasing the quantity of gains that can eventually be offset, as this article illustrates using historical market data.

Related

Average tax refund rises 11%; total filings decline

Prop. regs. issued on new qualified tips deduction

IRS releases FAQs on qualified overtime pay deduction under H.R. 1

Financial advisers frequently help clients plan for important life and financial milestones years in advance. Such events might include college education, major purchases, retirement, or even a sudden illness or death in the family. Life can be unpredictable, but proactive planning can bring peace of mind and prevent financial plans from being derailed.

The value of forward-looking preparation in the face of uncertainty also extends to tax planning. For example, tax and financial advisers may work with many clients with no immediate sources of capital gains but who are likely to realize significant capital gains in the future. This group includes entrepreneurs, real estate investors, homeowners, retirees, and passive investors.

This article analyzes through backtesting (described later) and cash flow analysis of hypothetical portfolios the potential benefit of accumulating capital losses in advance of expected capital gains in the future — in other words, the time value of capital losses. We test the benefits using two variations of tax-loss harvesting: (1) the traditional long-only approach and (2) a long-short tax-managed strategy that in many cases (but not always) provides even further value.

As expected, our study finds that “stockpiled” losses may add more value when the timeline for utilizing them is shorter. However, the magnitude of the effect of this timeline depends on many factors. Having short-term capital gains to offset increases the expected benefits of both loss-harvesting strategies, while liquidation of the portfolio at the end of the holding period reduces the overall tax advantages versus passing assets through an estate or to charity. Both tax and investment advisers can help their clients most when it is clear which situations warrant accumulating capital losses in advance of future capital gains.

Identifying future gains to offset

The benefits of systematic tax-loss harvesting are perhaps most obvious when the strategy is paired with investment strategies that consistently generate capital gains, such as certain types of hedge funds, active equity separately managed accounts, or active equity mutual funds.

However, gain-triggering events can take many forms, and countless taxpayers without regular sources of capital gains will need to periodically realize capital gains in the future, as illustrated in the following examples:

1. Asset allocation targets generally require rebalancing, which can generate gains in taxable accounts, even for investors who rely mainly on low turnover, tax-efficient vehicles such as indexed exchange-traded funds (ETFs).

2. Investors frequently need to reposition their portfolios as risk assessment shifts, active strategies may no longer seem appropriate, factor bets may change, or incorporating their values may lead to rebalancing.

3. One-time liquidity events such as selling a company or rental property can trigger significant capital gains.

4. Homeowners with the good fortune of significant unrealized price appreciation might choose to relocate for any number of reasons, which could cause capital gains in excess of statutory exclusions.1

A way to think about the strategy

One challenge of harvesting losses in advance of when they are needed is attempting to forecast capital gains. Future investment performance may be difficult to predict, and investor circumstances, objectives, or views may evolve over time.

Nonetheless, harvesting capital losses in anticipation of possible future capital gains, even though the value is obviously unknown, is analogous to many other conservative actions one may take, such as purchasing a first aid kit or a fire extinguisher, learning CPR, keeping jumper cables in the car, buying a warranty, or putting on a seat belt. In the right circumstances, systematically accumulating capital losses can serve as an insurance policy against all future capital gain recognition events, providing investors with enhanced flexibility to accomplish future goals with minimal tax consequences.

For noncorporate taxpayers, capital losses can offset capital gains and up to $3,000 of ordinary income on a federal income tax return. Excess capital losses carry forward indefinitely and may be used to offset capital gains recognized in future tax years.2

Although the benefits of tax-loss harvesting are largely deferred until there are capital gains available to offset, collecting losses over a multiyear period may allow an investor to offset significantly more capital gains than if a loss-harvesting program commences in the year of the taxation event. Capital gains must generally be recognized in the year they are generated and cannot be deferred or spread out over multiple years.3 Accordingly, only capital losses harvested in the year of the recognition event or realized in prior years and carried forward to that year are available to offset capital gains. Capital losses realized after the year of the taxation event generally cannot be carried back to offset gains generated in prior years.

In certain situations, the capital loss carryover rules may be more flexible and favorable for C corporations, which can generally carry capital losses back three years and then forward five years to offset capital gains. Although excess capital losses do not carry forward indefinitely, losses harvested within several years of a gain recognition event may be carried back to offset the previously recognized gains.4

The value of capital loss carryovers

The future benefits derived from generating capital loss carryovers through loss harvesting are determined by various factors, including:

Character of income or gains offset: For noncorporate taxpayers, capital losses that offset ordinary income or short-term capital gains may provide greater tax savings than those that offset long-term capital gains.

Tax rates: A taxpayer’s marginal tax rate may fluctuate over time due to changes in personal circumstances or tax legislation. The value of a capital loss carryover may increase in a rising tax rate environment and decrease as tax rates decline. Losses that offset short-term capital gains or ordinary income may be less valuable in years when a taxpayer is subject to the alternative minimum tax.

Timing of use: The benefits of capital losses decline as they carry forward unused and tax savings are deferred to future tax years, especially in inflationary environments.

Future disposition: Tax-loss harvesting reduces the basis of a portfolio and may result in the recognition of additional capital gains at liquidation. Investors who donate long-term appreciated securities to charity or pass them through an estate may enjoy the tax savings from loss harvesting while avoiding the realization of capital gains at disposition.

Strategies to increase loss-harvesting opportunities

When loss harvesting is beneficial for an investor, increasing overall opportunities to harvest losses can boost after-tax returns.

Loss-harvesting opportunities may increase significantly when investment returns are more volatile and widely distributed. Accordingly, individual stocks may offer greater loss-harvesting opportunities than equity mutual funds, equity ETFs, or bonds.

Investors may harvest losses with an ETF or mutual fund only if there is an embedded loss in the single pooled investment vehicle. However, in a direct indexing portfolio, which owns many of the underlying securities comprising an index, there may be many opportunities to harvest losses even if the overall index has experienced favorable returns.5

Relaxing long-only constraints and introducing margin and shorting to create a tax-managed public equity long-short portfolio may further boost overall loss-harvesting opportunities while adhering to an investor’s pretax investment thesis.

In such a long-short strategy, leverage is used to increase the overall gross exposure by introducing margin long exposures and short exposures, enhancing loss-harvesting opportunities both on the long and short side, in both upward-and downward-trending markets.

For example, the exposures in a long-only portfolio are 100% long and 0% short, whereas in a 130/30 long-short strategy, leverage is employed to increase exposures to 130% long and 30% short. In other words, for each $100 invested, the gross exposure of a 130/30 strategy is $160.

Estimating the potential amount of harvested losses

A backtest is one method of estimating the efficacy of an investment strategy by evaluating how it would have performed in predefined historical periods using corresponding historical market data. In our backtest, the hypothetical portfolios with a long-only equity direct indexing strategy funded with cash experienced increased cumulative losses as the strategy aged, although the amount of losses realized each year would tend to slow over time as the portfolios became more highly appreciated.

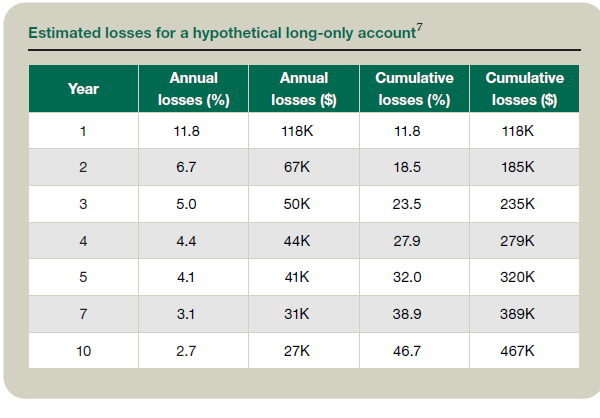

For example, as illustrated in the table “Estimated Losses for a Hypothetical Long-Only Account,” in the hypothetical cash-funded direct indexing accounts we backtested, losses as a percentage of initial cash funding for a hypothetical $1 million long-only account were on average approximately 11.8% in the first year, 32% over a five-year horizon, and 46.7% over a 10-year period. In other words, our backtest study showed that a $1 million cash-funded account may on average generate approximately $118,000 in capital losses during the first 12 months, approximately $320,000 over five years, and $467,000 over a 10-year period.6

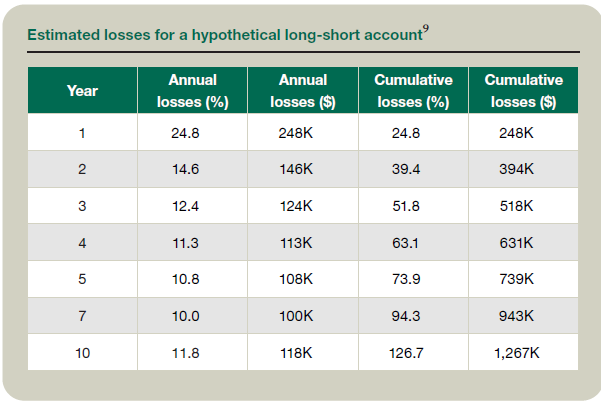

In comparison, tax-managed public equity long-short strategies may increase both the amount and the longevity of loss harvesting. For example, our backtest study showed that a hypothetical 130/30 long-short portfolio funded with cash tends to generate on average 2.7 times more capital losses than an average long-only account over the first 10 years (see the table “Estimated Losses for a Hypothetical Long-Short Account”).8

Calculating ‘tax alpha’ for the loss-harvesting strategy

Although stockpiling losses in advance may enable significantly more gains to be offset in future recognition events, the bulk of the loss-harvesting benefits will be delayed until there are capital gains available to absorb harvested losses.

Capital losses generate tax savings as they offset capital gains that would otherwise be taxable to investors. This tax savings can be reinvested and may compound over time. Accordingly, a dollar of tax savings realized in the current tax year is generally more valuable than a dollar of tax savings realized in a future tax year. For this reason, estimated “tax alpha” declines as capital losses carry forward unused and tax benefits are postponed to future tax years.

To quantify the potential economic benefit of tax-loss harvesting, we define “tax alpha” as the value of tax savings via capital gain reduction, scaled by the market value of the loss-harvesting portfolio. This definition provides three conveniences:

1. Tax alpha, as a measure of value addition through active tax management, is presented in percentage terms, which effectively allows it to be illustrated as a form of excess return from the loss-harvesting portfolio.

2. Representing tax alpha as an excess return also enables the overall tax benefit to be annualized. With annualized tax alpha, cumulative tax savings throughout the investment horizon is converted to an annual rate of return, “baking in” the size and timing of each tax benefit realization stemming from capital gain offset.

3. The magnitude of potential portfolio tax value addition can be examined and compared by both the sign and scale of its annualized tax alpha. A positive number indicates potential tax savings from loss harvesting, while a negative number indicates a potential tax drag from net gains realization. Larger positive tax alpha shows greater proportions of tax savings, whereas larger negative tax alpha shows more adverse tax drag. Lastly, due to the time value of money, upfront gains offset leads to higher annualized tax alpha, compared to delayed gains offset of the same characteristics and magnitude.

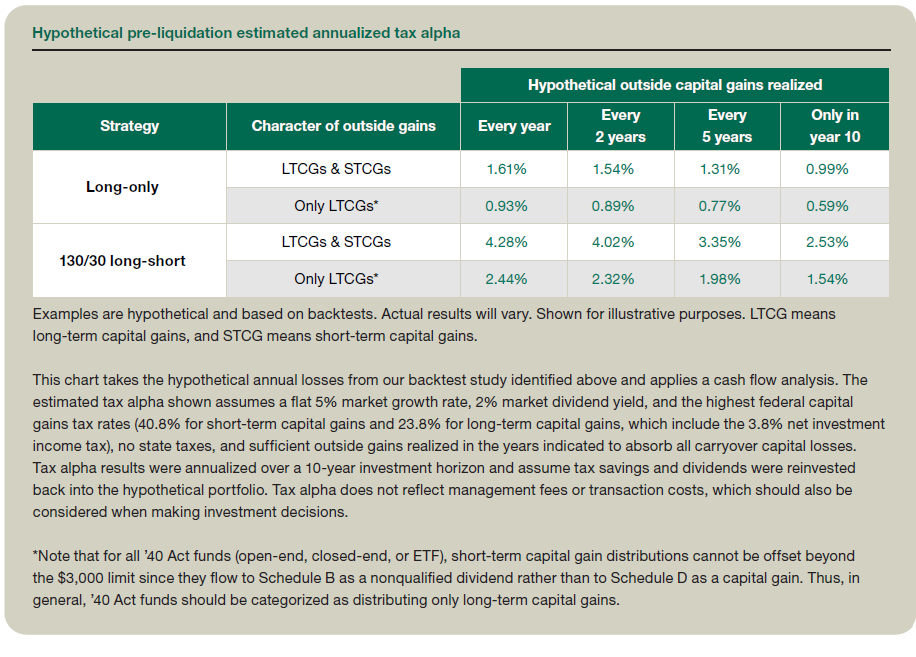

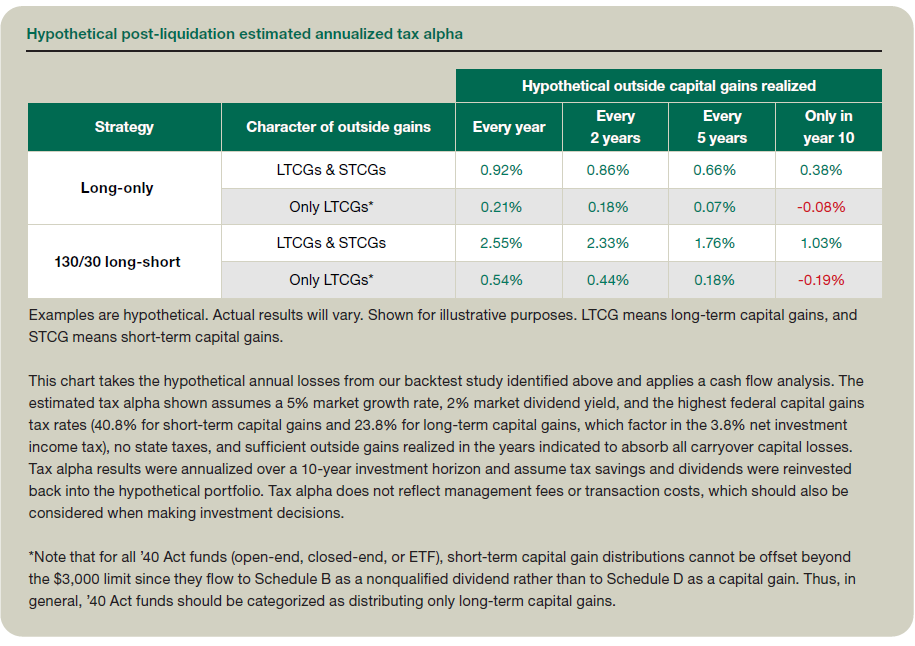

The effect of delayed tax savings is seen in hypothetical annualized tax alpha estimates for various loss-harvesting strategies and circumstances over a 10-year investment horizon. Recognizing the importance of an investor’s final disposition, we further grouped the hypothetical backtest results into two main categories: pre-liquidation and post-liquidation (see the tables “Hypothetical Pre-Liquidation Estimated Annualized Tax Alpha” and “Hypothetical Post-Liquidation Estimated Annualized Tax Alpha”). For the pre-liquidation scenario, we assume no action to the portfolio at the end of the investment horizon, and tax alpha is annualized over the accumulated tax benefits. For the post-liquidation scenario, we assume full liquidation of the portfolio at the end of the investment horizon, and tax alpha is annualized on both the accumulated tax benefits and the final liquidation tax drag. Due to the liquidation tax impact, annualized tax alpha under the post-liquidation case was smaller than under the pre-liquidation case.

In almost all hypothetical situations presented in our backtest, the estimated tax alpha for a hypothetical long-short portfolio is greater than its hypothetical long-only counterpart. Although our backtests showed that the estimated tax alpha of both long-only and long-short loss-harvesting strategies diminishes as the timeline for recognizing capital gains is extended, loss harvesting in advance of future capital gains may still be beneficial in certain circumstances, particularly if harvested losses will offset short-term capital gains or the portfolio will be donated to charity or held until there is an estate event.

Tax-loss harvesting in anticipation of future capital gains may be less favorable (or even harmful) for investors who plan to liquidate their portfolio in the future and who will only have long-term capital gains available to offset. Since capital gains realized in future years will be long-term in nature for many investors, advisers should carefully consider the expected disposition of the portfolio.

Liquidity considerations

Some investors may not have sufficient liquidity to fund a loss-harvesting portfolio with cash prior to an expected future exit or sale. For such investors, one possibility may be to fund the account by transitioning legacy securities.10

If this is not an option, it may be beneficial for the liquidity event to occur early in the year when possible, so a full year of harvested losses can be used to offset the realized gains. Employing a tax-managed long-short strategy may also significantly increase the quantity of losses that can be harvested in a single year.

Adjusting loss-harvesting efforts over time

Methodical tax-loss harvesting is not an all-or-nothing portfolio strategy — the intensity of loss harvesting can be ratcheted up or down as appropriate for an investor. Since available losses in public equity markets may dissipate if not timely harvested, and the quantity of losses available to be harvested each year tends to naturally decline as the strategy ages, systematically dialing loss-harvesting efforts up or down may never be warranted for investors who expect to recognize capital gains at least periodically in the future.

However, investors facing an outsized recognition event in a single year may have the flexibility (if their manager offers this customization) to adjust the intensity of loss harvesting, and long-short investors also have the flexibility to adjust margin over time as appropriate.

Trade-offs between long-only and long-short investing

Although there are many potential tax and nontax benefits to using a tax-managed long-short strategy, there are some downsides as well. Relative to a long-only separately managed account, there may be additional costs and fees in a long-short portfolio, such as a management fee premium, higher transaction costs due to greater turnover, and financing costs11 induced by margin and shorting.

Appreciated short positions may not be able to be donated to charity or qualify for a step-up in basis following an estate event. Liquidating appreciated short positions may be taxed at short-term capital gain rates and incur significant tax costs, even if held for longer than a year.

Finally, the use of leverage introduces additional complexities12 and its own performance risk since downside returns can be augmented. While most long-only direct indexing strategies are index-tracking in nature, long-short portfolio managers may elect to use signals13 to guide margin long and shorting preferences. As such, pretax performance of a tax-managed long-short strategy may deviate further from the market, resulting in additional active risk. Beyond that, margin and shorting may also introduce margin call and short recall risks.14 Investors and their advisers should carefully weigh the potential benefits and downsides before employing a tax-managed long-short strategy.

Advisers can help some investors realize large gains

Systematic tax-loss harvesting typically involves costs in the form of management fees, trading costs, additional operational complexity, and increased portfolio tracking error, so loss harvesting is generally not advisable for investors who will never recognize capital gains.15 However, many investors will need to realize capital gains at least periodically in the future.

Accumulating losses in anticipation of future recognition events may significantly increase the quantity of gains that can eventually be offset. However, the majority of the loss-harvesting benefits will be deferred until there are capital gains available to absorb harvested losses, and estimated tax alpha declines as the timeline for recognizing capital gains is postponed. Such a strategy tends to be most beneficial if harvested losses will offset short-term capital gains or if the investor plans to donate the portfolio to charity or pass it through an estate to receive a step-up in basis.

Tax-managed public equity long-short strategies may increase both the amount and the longevity of loss harvesting relative to a long-only portfolio, but there are also downsides to such a strategy that must be carefully considered.

Tax-loss harvesting in anticipation of future capital gains may provide tremendous tax benefits to some investors but, as illustrated in this article, is not appropriate in all situations, and advisers can help clients navigate relevant considerations.

Disclosure: Any tax information provided herein is for illustrative purposes only and does not constitute the provision of tax advice. Tax-loss harvesting strategies reflected in this article contain hypothetical information, including backtesting for illustrative purposes only. The hypothetical data used in this document does not reflect actual investments or trades. Backtesting may have fundamental errors and may produce inaccurate outputs when viewed against its design objective and intended business uses or particular needs of any individual investor.

Footnotes

1Individuals who meet certain ownership and use tests may be able to exclude up to $250,000 ($500,000 for married couples who file a joint return) of capital gains on the sale of their home. See Sec. 121.

2See Sec. 1211(b) and Sec. 1212(b)(1). In the case of a married individual filing separately, only $1,500 of ordinary income may be offset. Some states may not permit excess capital losses to carry forward to future tax years.

3Exceptions to this general rule exist. For example, in an installment sale, payment is spread out, and capital gains may be recognized over multiple years. Installment sale treatment is not available in all situations, such as the sale of publicly traded stock or securities.

4See Secs. 1211(a) and 1212(a).

5See Fleming, “The Economics of Tax-Loss Harvesting,” 54-9 The Tax Adviser 42 (September 2023).

6Results are from historical backtests and are for illustrative purposes only. The results for actual accounts will vary.

7The backtesting study’s material assumptions and estimation methodology are explained in the sidebar “Portfolio Construction Details and Assumptions for Backtest Study.” Hypothetical, backtested results are for illustrative purposes.

8See Goldberg, Cai, and Schneider, “A Guide to 130/30 Loss Harvesting,” Aperio (November 2023). These are the results of one backtest study. The results for actual accounts will vary.

9The backtesting study’s material assumptions and estimation methodology are explained in the sidebar “Portfolio Construction Details and Assumptions for Backtest Study.” Hypothetical, backtested results are for illustrative purposes.

10The cost-basis-to-market-value ratio of the existing securities will greatly impact a portfolio’s potential to harvest losses — estimated tax alpha decreases as this ratio declines. See Ulucam, “Tax Alpha: How Much Value Does Tax Management Add to a Legacy Portfolio?” Aperio (December 2023). If the existing securities are highly appreciated with few opportunities to harvest losses, adding leverage may help to rejuvenate their loss-generating capacity.

11A long/short investor pays margin interest on capital borrowed to finance the margin long positions and may receive a rebate payment on the proceeds from short selling.

12A full discussion of the tax issues to consider when implementing a long-short strategy, such as the straddle rules, constructive sale rules, and the economic substance doctrine, is beyond the scope of this article.

13Unlike a long-only direct indexing strategy, which tends to track an index, a long-short strategy may require directions and guidance on which securities are to be sold short, referred to as “signals.”

14Margin calls are triggered when a custodian demands more collateral, typically due to an aggressive upward drift in leverage. Short positions are also subject to recalls when a custodian demands that certain shorted stocks be purchased back and returned to the security lender.

15See Fleming, “Too Much of a Good Thing? Planning for Capital Loss Carryovers,” Tax Notes Federal (July 2022).

Contributors

Lincoln Fleming, CPA/PFS, CFP, M. Acc., is a senior tax economist in Highland, Utah, and Taotao Cai is a quantitative researcher and research infrastructure lead in Sausalito, Calif., both with Aperio Group LLC, a wholly owned, indirect subsidiary of BlackRock Inc. For more information about this article, contact thetaxadviser@aicpa.org.

AICPA & CIMA RESOURCES

Article

Fleming, “The Economics of Tax-Loss Harvesting,” 54-9 The Tax Adviser 42 (September 2023)

Podcast episode

“Taxes and Investment Planning,” AICPA PFP Section podcast (March 28, 2022)

CPE self-study

Investment Planning Certificate Program (Exam + Course)

For more information or to make a purchase, visit aicpa-cima.com/cpe-learning or call 888-777-7077.