- tax clinic

- INDIVIDUALS

Bidding farewell to US citizenship: Understanding the exit tax

Related

Prop. regs. issued on new qualified tips deduction

IRS releases FAQs on qualified overtime pay deduction under H.R. 1

IRS to start accepting and processing tax returns on Jan. 26

Editor: Rochelle Hodes, J.D., LL.M.

Expatriation is a major life decision with big tax implications for anybody thinking about giving up their U.S. citizenship or long-term permanent resident status. The U.S. Department of State urges anyone thinking about renouncing their U.S. citizenship to be aware that, in almost all circumstances, in addition to giving up the benefits granted to U.S. citizens, the act is irrevocable. In addition, individuals considering expatriation should carefully consider the costs associated with the U.S. exit tax under Sec. 877A and the potential for continuing U.S. tax obligations.

What is the exit tax?

Under Sec. 877A, a U.S. exit tax may apply to individuals who relinquish their U.S. citizenship or are long-term residents who cease to be a U.S. permanent resident. The tax is designed to make sure that all unpaid taxes are settled before a U.S. citizen or resident withdraws from the U.S. tax system. Individuals subject to the exit tax generally are assessed tax as if they had sold all of their assets the day before they left the country, also known as a “deemed distribution.”

The exit tax’s history and evolution

The U.S. tax system generally imposes tax on worldwide income. This is not the case in all countries.

The concept of an exit tax for expatriating individuals has a long-standing history in the United States, dating back to the late 19th century. Proponents believe that individuals should not be able to escape their U.S. tax responsibilities by relocating abroad to a country that exempts foreign-source income from tax.

More recently, high-profile cases of wealthy individuals renouncing their U. S. citizenship, seemingly to avoid U.S. taxation, sparked a debate surrounding the concept of an exit tax. In response, Congress enacted the first iteration of the current U.S. exit tax with the passage of the Heroes Earnings Assistance and Relief Tax (HEART) Act, P.L. 110-245, in 2008. The act codified amendments to Sec. 877 and new Sec. 877A, seeking to capture unrealized gains on assets and ensure that individuals settle their tax obligations before they exit the U.S. tax system.

Who must pay the exit tax?

Covered expatriates are subject to the exit tax. To determine if an individual is a covered expatriate, one must first determine whether the individual is an expatriate. U.S. citizens who relinquish their citizenship and long-term residents who cease to be a lawful permanent resident (holder of a green card) are expatriates for purposes of the exit tax. A long-term resident is an individual who has maintained lawful permanent resident status for eight or more of the previous 15 calendar years (Secs. 877A(g)(5) and 877(e)(2)). A year in which an individual claimed Treaty benefits to be treated as a foreign resident on Form 8833, Treaty-Based Return Position Disclosure Under Section 6114 or 7701(b), is not counted for purposes of the “eight of the previous 15 years” test.

Under Sec. 877A(g)(1), for an expatriate to be a covered expatriate, the individual must satisfy one of three tests under Sec. 877(a)(2):

1. Net worth test: The individual’s worldwide net worth is $2 million or more on the date of expatriation (i. E., the date the individual relinquishes U. S. citizenship or terminates long-term residency). This threshold is not adjusted for inflation.

2. Tax liability test: The individual’s average annual net income tax obligation for the five years ending prior to the individual’s date of expatriation exceeds the statutory threshold, which is indexed for inflation each year. For 2024, the threshold is $201,000.

3. Tax-compliance test: The individual fails to certify, under penalties of perjury, on Form 8854, Initial and Annual Expatriation Statement, that they have complied with all U.S. federal tax obligations for the five years prior to their expatriation.

Certain exceptions apply to status as a covered expatriate, such as those for dual citizens at birth and individuals expatriating before age 18½ (Sec. 877A(g)(1)(B)).

Calculating the exit tax

The primary elements of computing the exit tax include:

Mark-to-market regime: For most assets, a mark-to-market regime under Sec. 877A(a)(1) applies, treating the covered expatriate as if they sold their worldwide assets at fair market value (FMV) the day before expatriation. Any resulting gains above an exclusion amount ($866,000 in 2024) are subject to capital gains tax at generally applicable U.S. tax rates, based on the asset’s character and holding period.

Specified tax-deferred accounts: According to Sec. 877A(e)(1), specified tax-deferred accounts are treated uniquely in the context of expatriation. These include traditional individual retirement accounts (IRAs), Roth IRAs, health savings accounts, Archer medical savings accounts, Sec. 529 college savings plans, and Coverdell education savings accounts. On the day prior to an individual’s expatriation, these accounts are considered to be fully distributed (per Sec. 877A(e)(1)(A)), and the total amount is subject to taxation as ordinary income. Under Sec. 877A(e)(1)(B), except for certain situations involving Roth IRAs, early-distribution taxes generally do not apply (the exit tax consequences for Roth IRAs will vary based on the expatriate’s age, how long the Roth IRA has been held, and whether the deemed distribution is considered a qualified distribution).

Deferred compensation: The taxation of deferred compensation items depends on whether they are eligible or ineligible deferred compensation items. For deferred compensation to be classified as an eligible deferred compensation item, the payer must be a U. S. person, and the covered expatriate must notify the payer of his or her status as a covered expatriate and make an irrevocable waiver of any right to claim any reduction under any treaty with the United States in withholding on such item. The covered expatriate notifies the payer and makes the waiver by submitting Form W-8CE, Notice of Expatriation and Waiver of Treaty Benefits, to the payer on the earlier of the day before the first distribution on or after the expatriation date or 30 days after the expatriation date. Ineligible deferred compensation items are items that are not eligible deferred compensation items.

For eligible deferred compensation items, such as distributions from an eligible deferred compensation plan such as a 401(k) or employee pension plan, distributions are subject to 30% withholding at the time of distribution. Ineligible deferred compensation items, including certain foreign pension plans and vested but unexercised stock options, are taxed at ordinary-income rates as a lump-sum distribution of the present value of accrued benefits on the day before expatriation.

Beneficial interests in nongrantor trusts: Distributions of fixed, determinable, annual, or periodic income from nongrantor trusts to covered expatriates are subject to a 30% withholding tax at the time of distribution, and the trust may be required to recognize gains on distributed property exceeding its basis, effectively accelerating taxation on unrealized gains within the trust.

Example: A, a single U.S. citizen who used a calendar year for tax purposes, has decided to expatriate on Dec. 31, 2024. A is a covered expatriate based on the following: His net worth is $3.1 million, his average annual net income tax liability for 2018 through 2023 is $220,000, and he met all of his U.S. tax filing and payment obligations for those years. See the table “A’s Assets as a Covered Expatriate.”

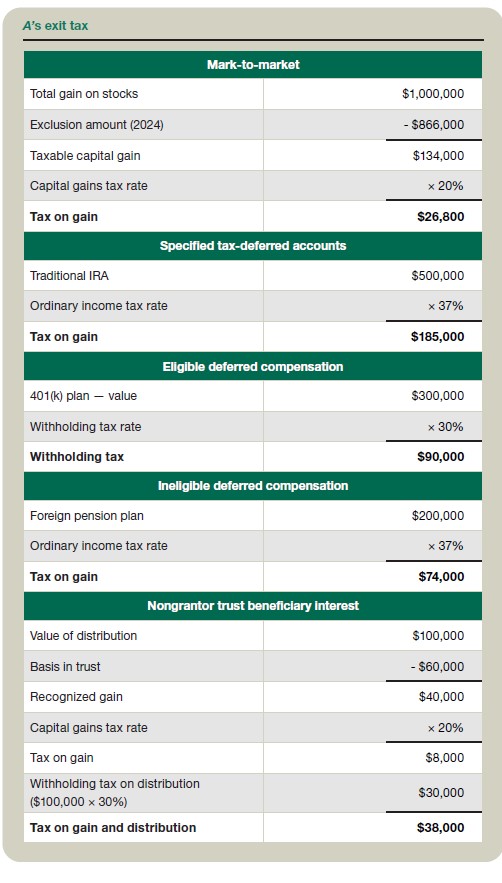

Based on this information, A’s exit tax is computed as shown in the table “A’s Exit Tax.”

The total exit tax is computed by adding amounts due for each type of asset above as follows: $26,800 (markto- market) + $185,000 (specified taxdeferred accounts) + $90,000 (eligible deferred compensation) + $74,000 (ineligible deferred compensation) + $38,000 (nongrantor trust beneficiary interest) = $413,800. The mark-tomarket items, specified tax-deferred accounts, and ineligible deferred compensation are taxed at the time of expatriation; the withholding tax on eligible deferred compensation and the nongrantor trust beneficiary interest is withheld at the time of distribution.

Net investment income tax

In addition to the exit tax, covered expatriates are subject to the net investment income tax under Sec. 1411, an additional tax of 3.8% that applies to certain types of investment income such as interest, capital gains, and dividends, once an individual’s income exceeds certain threshold amounts.

Planning considerations

While the exit tax cannot be entirely avoided for covered expatriates, the following strategies can potentially mitigate its impact.

Timing of expatriation: Carefully timing the expatriation date can influence factors such as net worth and average annual net income tax liability.

Asset transfers and gifting: Transferring or gifting assets before expatriation can reduce an individual’s net worth and potentially mitigate the exit tax’s impact on certain assets. However, these strategies must be executed well in advance of expatriation to avoid potential gift tax implications or the application of anti-abuse rules.

Retirement account planning: Exploring options for rolling over or distributing retirement accounts before expatriation may be advantageous in some cases. However, care should be taken because the taxation of these accounts can be complex and a higher exit tax is possible.

Trust and estate planning: Consider restructuring trusts, such as decanting or domesticating foreign trusts, and other estate planning strategies to manage the exit tax’s impact on beneficial interests and future distributions from nongrantor trusts.

Treaty considerations: Evaluate the applicability of income tax treaties and their potential to reduce or eliminate the exit tax components. Under certain income tax treaties, nonresident individuals may be exempt from being classified as long-term residents.

Valuation considerations: Specialized valuation expertise may be required to navigate the complexities of asset valuation in the context of expatriation planning. Factors such as discounts for lack of control and lack of marketability can significantly affect the valuation of assets, especially in the context of fractionalized ownership structures or transfers to family members.

Post-expatriation tax obligations

Even after expatriation, individuals may still have ongoing tax obligations. Some key post-expatriation U.S. federal tax obligations include:

Form 8854: Covered expatriates must file an initial Form 8854 with their timely filed return that includes the date of expatriation to confirm their tax compliance for the five years before expatriation. Certain expatriates will be required to file Form 8854 after they expatriate.

U. S.-source Income: Expatriates may still owe U.S. taxes on rental income, investments, and other U.S.- source earnings through withholding or reporting obligations. Additionally, under Sec. 1445 (Foreign Investment in Real Property Tax Act (FIRPTA) tax), expatriates may be required to pay U.S. tax on the gain from the sale of U.S. real property interests.

Retirement account distributions: Distributions from retirement accounts, including those deemed distributed as part of the exit tax calculation, may be subject to additional taxes or penalties, depending on the type of account and the individual’s age at the time of distribution.

Gift and estate taxes: At the time of expatriation, covered expatriates could be liable for transfer taxes on gifts or bequests to U.S. recipients made before expatriation, which could accelerate the taxation of these transfers.

Ongoing reporting requirements: Depending on the individual’s specific circumstances, there may be ongoing reporting requirements for income or accounts, even after expatriation.

Failure to comply with exit tax and expatriate U.S. federal tax obligations can result in substantial penalties and potential criminal liability. For instance, unless reasonable cause applies, a $10,000 penalty may apply to a failure to timely file a correct and complete Form 8854 when required for any tax year.

Planning and advice

Certain aspects of the rules for computing U.S. exit tax, such as tax imposed on certain assets under the mark-to-market regime and acceleration of tax on retirement accounts, can result in expatriates having to pay a higher tax than they would have paid if they did not expatriate. Strategic planning and expert tax advice are crucial to reduce this risk and avoid penalties post-expatriation. Maintaining open communication with experienced cross-border tax advisers can help individuals renouncing U.S. citizenship or residency have a more seamless transition from the U.S. tax system.

Editor notes

Rochelle Hodes, J.D., LL.M., is principal with Washington National Tax, Crowe LLP, in Washington, D.C.

For additional information about these items, contact Hodes at Rochelle.Hodes@crowe.com.

Contributors are members of or associated with Crowe LLP.