- column

- CASE STUDY

Deferring gain in liquidation with an installment sale and noncompete agreement

Liquidating S corporations may defer corporate-level gain by distributing a qualifying installment obligation arising in a 12-month liquidation period; a planning strategy pairs this exception with a noncompete agreement.

Related

Buy/sell agreements for S corporations

PTEs need more notice of changes, more time to respond, AICPA says

Late election relief in recent IRS letter rulings

An S corporation can use a planning strategy to defer gain recognition through the use of a qualifying installment obligation and a covenant not to compete. The examples below illustrate this strategy and the tax consequences of failing to qualify for installment reporting when a nonqualifying installment obligation is distributed.

Distributing a qualifying installment obligation

The distribution of an installment obligation by a corporation in liquidation will normally trigger corporate gain. However, an important exception allows S corporations to distribute qualifying installment obligations arising within the 12–month liquidation period without triggering gain at the corporate level. This exception does not apply to existing installment obligations that may have arisen from the sale of assets in periods prior to the adoption of the plan of liquidation. (It also does not apply to any built–in gain taxed under Sec. 1374.) The following example uses this exception to illustrate the opportunity for deferred installment sale reporting upon the sale and liquidation of the S corporation.

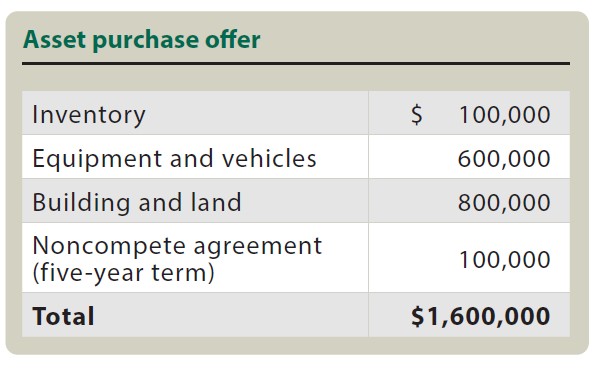

Example 1. Deferring gain on liquidation through the use of a qualifying installment obligation and a covenant not to compete: S Inc. is a small manufacturing company owned entirely by employee–shareholder M, who is nearing retirement and has listed the business for sale with a business broker. S has been an S corporation since its formation. In June of the current year, the broker approaches M with an offer to purchase S’s assets as shown in the table “Asset Purchase Offer,” below.

The buyer proposes to pay $600,000 in cash for the equipment and vehicles. The buyer will pay M $20,000 per year over the five–year term for the noncompete agreement (which is valid under state law) and $80,000 per year plus interest over 10 years for the real estate. Under the terms of the offer, the inventory would be calculated at book value and sold for cash as of the closing date (estimated to be $100,000). The other assets, such as cash and receivables net of accounts payable, are valued at $200,000 and would not be part of the sale. If M accepts the buyer’s proposed offer, the deal would close in November of the current year.

S has an adjusted tax basis of $200,000 in its equipment and vehicles and $300,000 in its real estate. M has an adjusted basis in his stock of $800,000 and would like to liquidate the corporation when the assets are sold. M decides to accept the offer, which provides the opportunity for deferred installment gain reporting on the sale and liquidation of S.

Computing the corporate gain on asset sale

The installment method of reporting is available to recognize gain on an asset sale (Sec. 453(a)). However, depreciation recapture under Secs. 1245 and 1250 is always reportable in the year of sale, representing a limitation to the ability to use installment reporting (Sec. 453(i)). In this example, assume Sec. 1245 recapture applies to the sale of the equipment and vehicles. However, assume there is no Sec. 1250 recapture associated with the building sale.

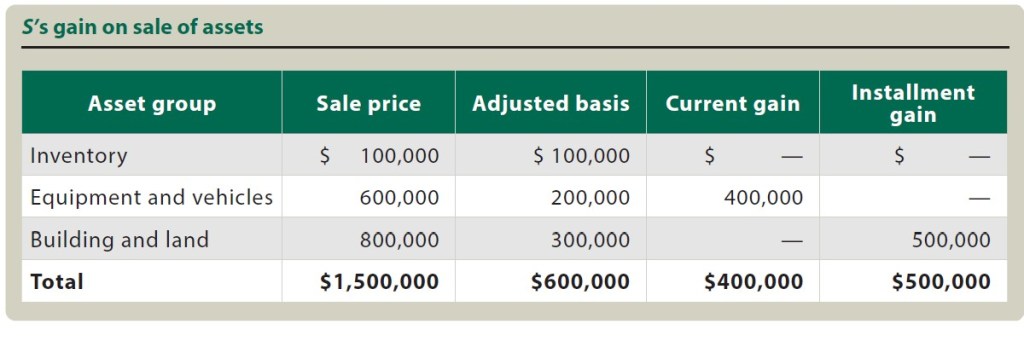

Overall gain: The gain S would report on the sale of its assets is calculated as shown in the table “S’s Gain on Sale of Assets,” below.

Recapture gain: It is not possible for S to achieve any deferred or installment reporting associated with its equipment and vehicles because of the recapture rule. Even if the buyer spreads the payments for the $600,000 purchase of the equipment and vehicles over more than one year, the entire gain is reportable in the year of sale because of the Sec. 1245 recapture (assuming that the sale price of equipment and vehicles, in the case of each asset, is less than the original cost of the asset to S).

Determining who owns goodwill: When goodwill is owned by the employee–shareholder, it may be possible to reduce double taxation on a corporate liquidation following an asset sale. The courts have distinguished between personal and corporate ownership of goodwill depending on whether the employee–shareholder had an ongoing employment contract and a contract not to compete. When there was no such contract during the term of employment, the goodwill may be personal to the shareholder. However, when the employee worked for the corporation under the terms of an employment contract and with an agreement not to compete with that corporation, the corporation, rather than the individual employee, normally owns the goodwill (Howard, 448 Fed. Appx. 752 (9th Cir. 2011)).

Under the facts of Example 1, the corporation is not subject to the built–in gains tax (it has always been an S corporation). If it were, goodwill could be an important component of the gain subject to tax. Assume the corporation does not have a noncompete agreement with M during the time he worked for the corporation. Accordingly, M, rather than the corporation, would be considered the owner of any goodwill generated through his personal services to the corporation.

Structuring the noncompete agreement: The $100,000 payment for the noncompete agreement in Example 1, payable at $20,000 per year, should be structured as a direct payment from the buyer to M. The agreement pertains to restrictions against personal services in the future by M and does not represent the sale of a corporate asset.

The $20,000 annual payment is reportable by M each year as ordinary income (Chiappetti, T.C. Memo. 1996–183). The payments are not subject to self–employment tax (Barrett, 58 T.C. 284 (1972)).

Because the purchaser acquires the noncompete agreement in connection with the acquisition of an interest in a trade or business, the purchaser must treat the noncompete agreement as a Sec. 197 intangible and amortize it for tax purposes over 15 years (Sec. 197(d)(1)(E); Frontier Chevrolet, 329 F.3d 1131 (9th Cir. 2003)). Note that the actual period of the covenant not to compete will normally be less than 15 years due to legal enforceability requirements under applicable state law.

Computing the shareholder gain on liquidation

A distribution by a corporation of its assets in liquidation is treated as if the corporation had sold its assets at fair market value (FMV) (Sec. 336(a)), resulting in corporate recognition of gain or loss (whether or not the actual assets are distributed or the assets are sold and the sales proceeds distributed).

Following S’s sale of the inventory, equipment, vehicles, and real estate, the only assets remaining are cash, accounts receivable (net of accounts payable), and the note receivable associated with the sale of the real estate (see Example 1). Because the installment obligation is acquired by the S corporation from the sale of its assets during the 12–month period beginning on the date of adoption of a plan of complete liquidation and is then distributed to the S shareholder as part of the liquidation, no gain or loss is recognized by the S corporation on the distribution of the installment note (Sec. 453B(h)).

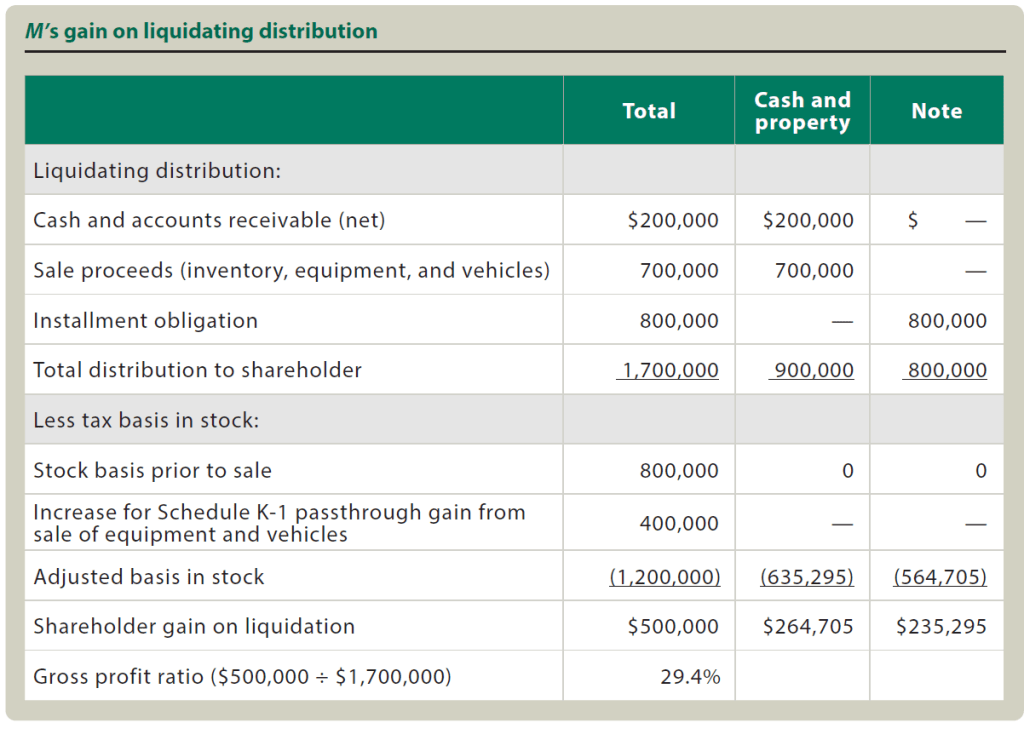

The shareholder’s gain on the liquidating distribution is calculated as shown in the table “M’s Gain on Liquidating Distribution,” below.

If a shareholder receives a qualifying installment note in exchange for stock in a liquidation, the receipt of payments on the installment note is treated as the receipt of payments for the stock if certain conditions are met.

The note M receives is a qualifying installment obligation. As shown in the previous computation, M’s gross profit ratio is 29.4%. M is treated as having received $900,000 ($200,000 + $700,000) in payments and is required to recognize $264,705 of gain. This gain is characterized based on the type of asset sold (stock) and treated as capital gain.

The character of the shareholder’s computed gain or loss on the installment obligation is determined at the corporate level (Sec. 453B(h), last sentence; Regs. Sec. 1.453–11(a)(2)). This rule prevents the conversion of ordinary gain at the corporate level into capital gain at the shareholder level. Similarly, gain resulting from an installment sale of property that produces short–term capital gain (because it was held less than one year) cannot be converted into long–term capital gain by reference to the holding period of the shareholder’s stock.

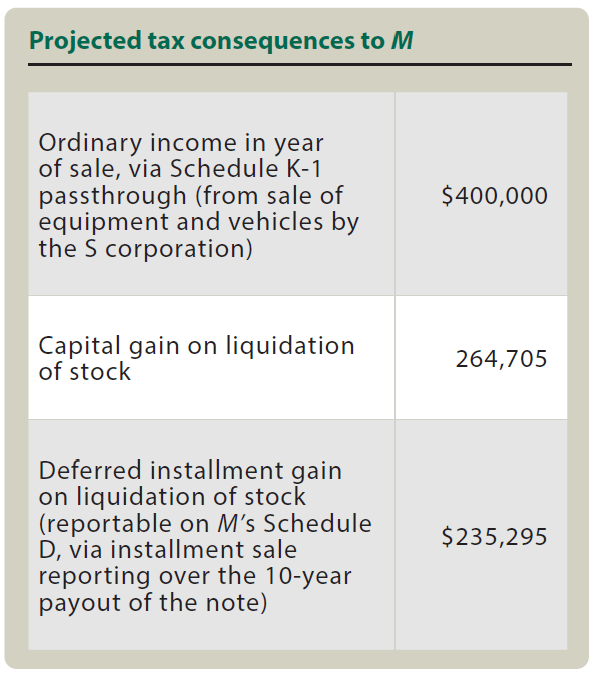

Accordingly, the projected tax consequences to M in Example 1 are as shown in the table “Projected Tax Consequences to M,” below.

Distributing a nonqualifying installment obligation

Example 2 below and the related discussion illustrate the tax consequences of failing to qualify for installment reporting when a nonqualifying installment obligation is distributed.

Example 2. Distribution of a nonqualifying installment obligation in a liquidation: Assume the same facts as in Example 1, except S holds an installment receivable that arose four years ago from the sale of vacant land adjacent to its building. At that time, S determined that it no longer needed the real estate in its business and sold the land under a 10–year installment contract. Currently, at the point of proposed liquidation of S, this installment obligation has a remaining face amount and FMV of $400,000 and an adjusted basis of $100,000.

The distribution of this existing installment obligation in liquidation will trigger the entire gain to S (and consequently to M under the S corporation passthrough rules) (Sec. 453B(a)).

Furthermore, any sale of this obligation to the buyer or rollover of the note into the buyer’s new obligation would trigger gain on the original obligation.

Because S has always been an S corporation and therefore has no accumulated earnings and profits (AE&P), it has no particular incentive to liquidate. Thus, S might simply remain in existence without liquidating and continue to collect on the installment obligation over the term of the note. However, this technique is valid only because S does not have prior C corporation earnings and profits and is thus not subject to the tax on excess net passive income.

If S had previously been a C corporation and currently had accumulated C corporation earnings and profits, it could potentially be subject to the passive income tax facing S corporations if it continued in existence while not conducting an active trade or business and while receiving interest income from the installment obligation (Sec. 1375). Furthermore, if it had AE&P and passive investment income of more than 25% of gross receipts for three consecutive years, its S election would terminate (Sec. 1362(d)(3)).

Contributor

Shaun M. Hunley, J.D., LL.M., is an executive editor with Thomson Reuters Checkpoint.For more information about this column, contact thetaxadviser@aicpa.org. This case study has been adapted from Checkpoint Tax Planning and Advisory Guide’s S Corporations topic. Published by Thomson Reuters, Frisco, Texas, 2025 (800-431-9025; tax.thomsonreuters.com).