- tax clinic

- INTERNATIONAL

A transfer pricing paradox: High-risk transactions remain underrepresented in APAs

Related

Businesses urge Treasury to destroy BOI data and finalize exemption

IRS generally eliminates 5% safe harbor for determining beginning of construction for wind and solar projects

Deducting corporate charitable contributions

Editor: Christine M. Turgeon, CPA

The IRS in 2024 reiterated its intention to continue to strengthen its transfer pricing enforcement capabilities, explicitly noting its willingness to assert penalties even in cases where transfer pricing documentation is prepared (Brad Anwyll, IRS Transfer Pricing Practice director of field operations, speaking at the Tax Executives Institute Conference, Tysons, Va., Sept. 10, 2024; see Harshberger, “IRS Staffs Up Transfer Pricing Enforcement Boost With New Hires,” Daily Tax Report (Sept. 10, 2024)). As the risk for transfer pricing disputes continues to rise, taxpayers may want to make concerted efforts to avoid protracted audits and costly adjustments. Advance pricing agreements (APAs) offer legal certainty to both taxpayers and the IRS with respect to transfer pricing matters; however, there is a notable discrepancy between the types of transactions for which taxpayers pursue APAs and those targeted by IRS–initiated audits. This discrepancy raises concerns that the IRS Advance Pricing and Mutual Agreement (APMA) Program’s APAs are not being sought where certainty may be most valuable to both taxpayers and the IRS.

The IRS scrutinizes intangible property transactions due to pricing difficulties and materiality

Intangible property transactions provide some of the most challenging transfer pricing issues. In IRS–initiated transfer pricing audits, intangible property transactions consistently present contentious and high–risk issues for taxpayers. More specifically, intangible property transactions such as licensing arrangements, transfers of intangible assets, and cost–sharing arrangements frequently are scrutinized for several reasons.

First, valuing intangible assets is inherently difficult. Unlike tangible goods, the uniqueness of intangibles makes finding reliable comparables a challenge, and viable pricing methods necessarily may be limited as a result. Further, those limited methods may have a number of subjective elements that serve as fuel for potential tax controversies. In many tax controversies over the years involving intangibles, one of the issues has been whether the subject intangible is even compensable under the regulations. In an effort to refine methods for valuing intangible property between related parties, profit–based transfer pricing methods were introduced under Regs. Sec. 1.482–4 in 1994. This shift occurred because the comparable–uncontrolled–price method was proving insufficient for valuing intangible property due to the unique and noncomparable nature of many intangibles, leading to the adoption of methods that consider overall profitability rather than direct price comparisons.

Additionally, intangible assets are typically the most valuable assets owned by multinationals. Thus, even minor adjustments to intangible property transactions have the potential to increase tax liability significantly. Some of the most recent U.S. transfer pricing court cases primarily involve intangible property transactions and have proposed billions of dollars in transfer pricing adjustments. It is therefore unsurprising that the IRS continually has focused on auditing intangible property transactions.

Intangible property transactions consistently represent the minority of transactions covered in the APA program

The only way taxpayers proactively can achieve legal transfer pricing certainty in the United States is through APMA’s APA program. APAs preemptively address the appropriate transfer pricing method for covered transactions over a specified period. By addressing these issues in advance, both the IRS and taxpayers are provided with the opportunity to collaboratively discuss and resolve the issues on a principled basis, which ultimately provides greater certainty for the taxpayer and the IRS through a binding legal agreement. If a taxpayer complies with the agreed–upon pricing for a specific transaction in an APA, the IRS cannot make adjustments to the covered transaction. Only under certain rare circumstances such as fraud, malfeasance, misrepresentation of material facts, or violation of a critical assumption does the IRS have the authority to revoke or cancel an APA (see Rev. Proc. 2015–41, §7.06). Thus, for complex issues such as intangible property transactions, an APA seemingly would be an appropriate path for a taxpayer to mitigate the risk of an audit. Yet, intangible property transactions represent the minority of transactions covered under APAs.

Resolving the appropriate transfer pricing treatment for an intangible property transaction through an APA is also a preferred outcome for the IRS, as an APA can guarantee a certain result for many prospective years. The APA relieves the IRS from having to devote further compliance resources to audit transfer pricing issues, other than an annual review of compliance with the agreed–upon approach. Additionally, the nature of mutually negotiating and agreeing on appropriate pricing with the counterparty jurisdiction at the table tends to result in a satisfactory outcome for both parties. Audits, on the other hand, could result in extreme proposed adjustments that are derived without the influence of the counterparty’s positioning or views on the case. Audits thereby present greater risk for both the IRS and the taxpayer.

For example, in the absence of a bilateral APA, the foreign counterparty may come to the table with a large adjustment that has to be resolved through a mutual agreement procedure. The large adjustment may affect the negotiating dynamics compared to a bilateral APA negotiation, where the competent authorities come to the table even–handed. Similarly, an audit may evolve into costly and lengthy litigation where either the IRS or the taxpayer may enjoy a winner–take–all result, but only by undertaking great litigation risk (especially the taxpayer, which may be subject to double taxation if it loses and cannot assess the counterparty). The time and expense needed to conclude an APA receive a lot of attention, but the APA process may be more efficient than even a relatively amicable transfer pricing audit. It would thus seem that APAs involving intangible property transactions would be exceedingly prevalent. However, a closer look at the makeup of transactions covered by APAs reveals that these intangible property transactions consistently represent the minority.

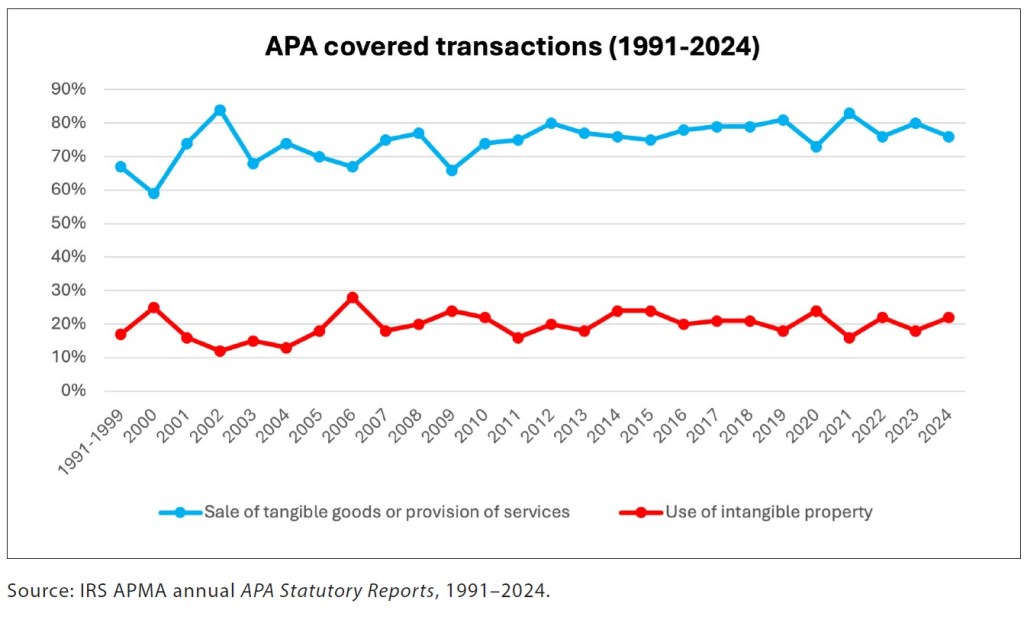

According to APMA’s APA Statutory Report for the year ended Dec. 31, 2024, APMA executed 142 APAs, slightly down from a record high of 156 APAs executed in 2023. Notably, 76% of the covered transactions under these APAs related to either the sale of tangible goods or the provision of services, whereas only 22% related to the use of intangible property. This trend is consistent with APMA’s portfolio of APAs since the start of the APA program in 1991. The graph “APA Covered Transactions (1991—2024),” below, indicates that the use of intangible property has made up approximately 20% of the covered transactions in APMA’s portfolio of APAs, while transactions involving the sale of tangible goods or provision of services have comprised approximately 75% of covered transactions.

The graph makes clear that APMA’s APA portfolio is heavily weighted toward transactions involving tangible goods and services rather than intangible property. Several key factors contribute to this trend. One primary reason is that taxpayers often seek APAs for transactions that may seem routine from a U.S. perspective but pose a higher risk with U.S. treaty partners. For example, this reason may include certain transactions that are the subject of frequent audits and adjustments by the U.S. treaty partners.

Another significant factor is that risk–averse taxpayers may be less concerned about these types of transactions. Unlike complex intangible property transactions, the transactions that predominantly make up the APA program generally are easier to document and resolve in a bilateral negotiation. The benefits of cost savings and predictability may diminish when dealing with intricate intellectual property arrangements.

Instead, taxpayers tend to opt for the so–called “document–and–defend” approach when it comes to intangible property transactions. Under this approach, taxpayers focus on maintaining robust Sec. 6662 documentation, among other best practices, to defend their position in the case that their transaction is selected for audit. By proposing to cover potentially contentious intangible property transactions under APAs, a taxpayer may run the risk of subjecting itself to audit by bringing the IRS’s attention to a high–risk transaction if APMA rejects the case.

Finally, the recurring nature of tangible goods and services transactions reinforces their dominance in the IRS APA portfolio. These transactions often persist over multiple years, allowing for repeated renewals, which increases the efficiency and usefulness of the APA process. In contrast, certain intellectual property transactions, such as one–time transfers, are often less consistent over time. This irregularity reduces the practical benefits of APAs, making them less attractive for taxpayers.

Observations to encourage APAs for intangibles

APMA’s APA program was established with the intention of dedicating resources to provide certainty for high–risk issues for both taxpayers and the IRS. However, APAs are not being pursued for transactions that have the most to gain from certainty. Despite this fact, the IRS more recently has reinforced its commitment to addressing complex issues through its APA program. In May 2023, in light of concerns that the memorandum Interim Guidance on Review and Acceptance of Advance Pricing Agreement (APA) Submissions (LB&I–04–0423–0006 (April 25, 2023)) indicated APMA’s reluctance to accept difficult cases in the APA program, the IRS publicly refuted this notion, stating that APMA remains dedicated to handling complex transactions (Nicole Welch, acting director, IRS Treaty and Transfer Pricing Operations Practice Area, speaking at the Pacific Rim Tax Conference, San Francisco, May 18, 2023).

Ultimately, if APMA is willing to accept complex transactions in the APA program, in order to ensure its resources are being allocated to transactions where certainty is most valuable to taxpayers and the IRS, it could incentivize taxpayers to pursue APAs for these issues. APMA could make efforts to establish trust with taxpayers so that they do not fear that proposing a complex intangible property transaction effectively may subject themselves to audit. Another approach could be enhancing APMA’s APA Statutory Reports by including additional statistics such as resolution times and acceptance rates categorized by transaction type or details on the transactions in rejected, revoked, or withdrawn APAs. These insights could help taxpayers better gauge the likelihood of success for complex APAs. Additionally, APMA could offer guidance for APAs involving intangible property to streamline the post–submission process. For instance, providing typical information request items related to intangible property transactions could help taxpayers address these requirements proactively. These recommendations could be incorporated into a new APA revenue procedure.

Editor

Christine M. Turgeon, CPA, is a partner with PwC US Tax LLP, Washington National Tax Services, in New York City.

For additional information about these items, contact Turgeon at christine.turgeon@pwc.com.

Contributors are members of or associated with PwC US Tax LLP.