- tax clinic

- GAINS & LOSSES

Estate of McKelvey highlights potential tax pitfalls of variable prepaid forward contracts

Related

Murrin and Zuch provide insight into the limits of taxpayers’ rights

IRS generally eliminates 5% safe harbor for determining beginning of construction for wind and solar projects

IRS rules that community trust and affiliated nonprofit corporation can file a single Form 990

Editor: Jessica L. Jeane, J.D.

In Estate of McKelvey, 161 T.C. 130 (2023), the Tax Court resolved a long–simmering dispute regarding a little–known financial instrument called a variable prepaid forward contract (VPFC). The unique facts of the case produced an unfavorable result for the taxpayer, but the taxpayer’s misfortunes offer several lessons for tax advisers.

Case background

Andrew McKelvey was the founder and former CEO of Monster Worldwide Inc. As such, he held a large amount of Monster stock with zero basis.

In 2007, McKelvey established VPFCs with two banks, Bank of America (BOA) and Morgan Stanley (MSI). In a VPFC, a shareholder contracts with a bank to deliver a variable number of shares at a predetermined future date. In exchange, the shareholder receives a prepayment based on a discounted amount of the stock’s present value. Assuming certain conditions are met, VPFCs allow a shareholder to diversify and monetize a concentrated stock position while deferring gain. McKelvey’s VPFCs complied with Rev. Rul. 2003–7. Accordingly, he did not report any gain or loss for 2007.

The amount of stock to be delivered was determined by a formula, which considered the closing price of the stock at the time of settlement in relation to a floor price and a cap price. The floor and cap prices established a trading range for the stock similar to a collar transaction. The VPFCs had three possible settlement outcomes:

- If the closing price was equal to or below the floor price, then McKelvey was required to deliver the maximum number of shares specified in the contract.

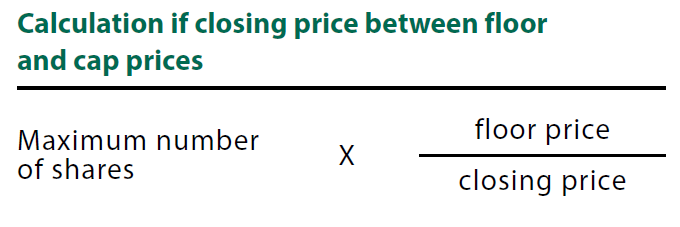

- If the closing price was between the floor and cap prices, then the number of shares to be delivered was an amount less than the maximum number of shares, calculated as shown in the graphic “Calculation If Closing Price Between Floor and Cap Prices.”

- If the closing price exceeded the cap price, then the number of shares to be delivered was calculated as shown in the graphic “Calculation If Closing Price Exceeds Cap Price.”

Shortly before the 2008 settlement date of the original VPFCs, McKelvey extended the contracts until 2010. McKelvey, who was terminally ill at the time, presumably sought the extension to defer his large unrealized gains in Monster stock until his death, at which time a step–up in basis under Sec. 1014 would eliminate his gain. McKelvey died in 2008, four months after the extensions. Neither McKelvey nor his estate recognized any gain on the Monster stock that was part of the VPFCs.

In a notice of deficiency, the IRS argued that the 2008 modifications to the VPFCs resulted in taxable exchanges under Sec. 1001. When the matter first went to the Tax Court (Estate of McKelvey, 148 T.C. 312 (2017), McKelvey I), the court ruled in favor of McKelvey. Upon appeal (Estate of McKelvey, 906 F.3d 26 (2d Cir. 2018), McKelvey II), the Second Circuit reversed the Tax Court’s decision. The appeals court agreed with the IRS’s argument that the share price of the stock pledged as collateral was so far below the floor price that the number of shares to be delivered at settlement was “substantially fixed” within the meaning of Sec. 1259(d)(1), thus triggering the constructive–sale rules. After this ruling, the parties stipulated that the amount of long–term capital gain from the constructive sale of Monster stock amounted to $102,406,962.

Furthermore, while the Second Circuit agreed with the Tax Court’s determination that the VPFC extension was not an “exchange of property” under Sec. 1001(c), the Second Circuit also agreed with the IRS’s argument that extending the contracts was a “fundamental change” that resulted in new VPFC contracts replacing the original VPFC. The Second Circuit remanded the decision as to whether the VPFC extension terminated McKelvey’s original obligation for purposes of Sec. 1234A. On remand, the Tax Court (Estate of McKelvey, 161 T.C. 130 (2023), McKelvey III) concluded that there was a termination of obligations under Sec. 1234A with respect to the VPFC extension.

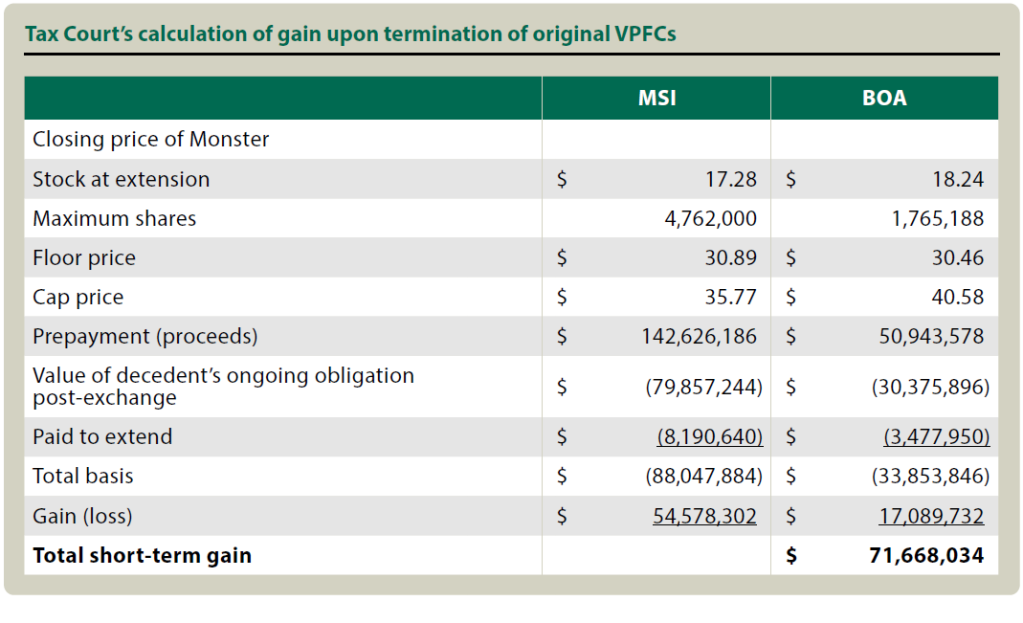

The Tax Court calculated McKelvey’s gain on the VPFC extension under Sec. 1001. For proceeds, the court used the original prepayment amount. To calculate tax basis, the court used the amounts paid to extend the contracts as well as the calculation of the decedent’s ongoing obligation as calculated by the IRS’s financial expert using the Black–Scholes method. (See the table “Tax Court’s Calculation of Gain Upon Termination of Original VPFCs.”)

Unusual fact pattern highlights several potential pitfalls

Shortly after McKelvey created the VPFCs, a global financial crisis triggered a stock market meltdown. Monster stock traded at $32.97 when the BOA VPFC was created and $34.06 when the MSI VPFC was created. Only 10 months later, when the contracts were extended, the stock traded at $18.24 (BOA) and $17.28 (MSI) per share. The result of this precipitous fall in stock price was that a straight–up extension of the original contract no longer made economic sense under the old terms. Despite materially different market conditions from when the VPFCs were established, McKelvey forged ahead with an extension of the contracts using the same floor and cap prices specified in the original VPFCs. The result was both a constructive sale and a termination of obligation that gave rise to taxable gain in 2008.

Constructive sale

The Second Circuit determined that the probability that anything other than the maximum number of shares would be delivered was sufficiently low, less than 15%, per the IRS’s financial expert. Barring a miraculous recovery in Monster’s stock price, the eventual settlement of the extended VPFCs with the maximum number of shares was a foregone conclusion, at least statistically. As for what probability is necessary to trigger the constructive–sale rules, the court offered no bright line. It simply acknowledged that in McKelvey “the percentages are very high” and the share prices “were so low as to be barely more than half of the floor prices” (McKelvey II). As a result, the court determined that the amount of property to be delivered was substantially fixed for purposes of Sec. 1259(d)(1) as of the extension date, so the constructive–sale rule applied.

In an alternative fact pattern where Monster stock traded closer to the VPFC’s established trading range, it seems unlikely that Sec. 1259 would apply. The IRS’s expert witness conducted a probability analysis on the original VPFC contracts. He determined that at the time the VPFCs were created, the probability that the closing price would be greater than the floor price on settlement was slightly greater than 50%. In such a scenario where the stock is within the trading range, the number of shares to be delivered is not substantially fixed, and the constructive–sale rules should not apply. The Second Circuit even acknowledged that it was a “somewhat limited frequency of situations in which amendment of the valuation date of a VPFC will create liability for capital gains taxes” (McKelvey II).

Despite this rarity, tax advisers should still carefully consider whether the constructive–sale rules apply when their clients establish a new VPFC or roll an existing position. The terms of the contract and the trading range should appropriately reflect current market conditions. When the stock price has declined below the floor price, tax advisers must remain vigilant as to potential gain recognition under Sec. 1259.

Termination of obligation

As detailed in the table “Tax Court’s Calculation of Gain Upon Termination of Original VPFCs,” above, the deemed exchange of the old VPFCs for the new VPFCs led to a substantial recognized gain, which makes economic sense. McKelvey received prepayment based on a share price of $33–$34 per share. This was protected from losses below $30 per share, and McKelvey had an obligation to deliver shares worth only $17–$18 per share. McKelvey benefited from the downside protection inherent in a VPFC, and he was accordingly taxed on that benefit.

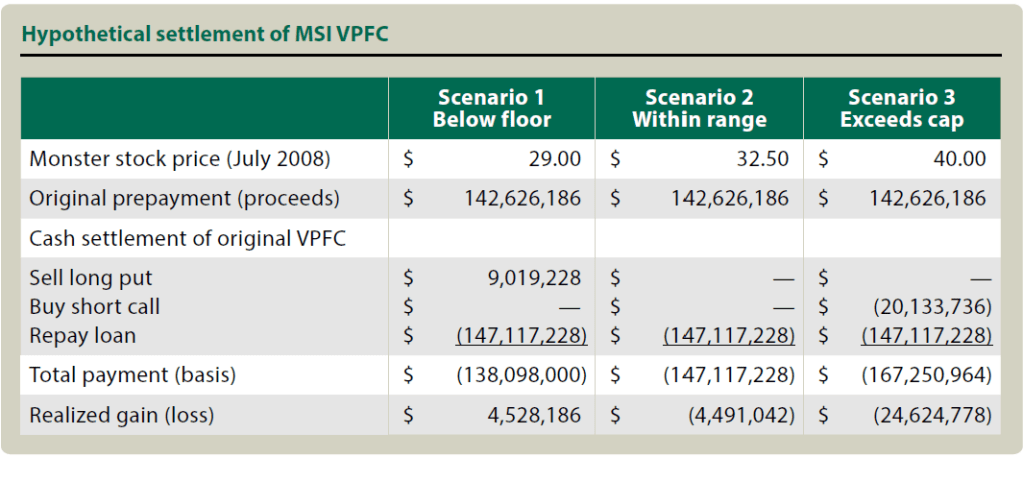

Since the Tax Court’s ruling, tax advisers should carefully consider whether an extension or roll of an expiring contract might create a taxable event. Returning to our alternative fact pattern where the global financial crisis never occurred, consider the potential taxable ramifications of three scenarios under the terms of the MSI contract:

- Scenario 1: Stock trading slightly below floor ($29 per share).

- Scenario 2: Stock trading between floor and cap prices ($32.50 per share).

- Scenario 3: Stock trading above the cap price ($40 per share).

In the table “Hypothetical Settlement of MSI VPFC,” below, we assumed that McKelvey rolled his position by executing a cash settlement of the old VPFCs and created new VPFCs. We adapted Liberman and Sosner’s analysis of the cash flows of a VPFC roll to illustrate the tax effect of each scenario (Liberman and Sosner, “A Brief Guide to Pricing and Taxation of Variable Prepaid Forwards,” 27 The Journal of Wealth Management 99 (Spring 2025)).

The cost to unwind the original VPFC is a function of three components. First, the put position, which provides downside protection, must be sold. If the stock is below the floor, as in Scenario 1, then the put is “in the money” and generates gain upon sale. If the stock is above the floor, as in Scenarios 2 and 3, then the put is worthless.

Second, the call position must be closed through a buy. The call position establishes the upper limit of the trading range (i.e., the cap price). If the stock is above the cap price, then the call position is in the money, and there is a cost to closing the short position. Otherwise, the call is worthless. Third, the loan that funds the original prepayment must be repaid. The amount of the loan represents the put–protected amount, i.e., the maximum number of pledged shares multiplied by the floor price.

While the table “Hypothetical Settlement of MSI VPFC” is an extremely simplified analysis, it highlights a few key issues for tax advisers to consider. When the stock price falls below the floor at the time of the roll, advisers should be aware of the potential for realized gain. Just like the actual result in McKelvey, the shareholder in Scenario 1 realizes a gain when the share price falls below the floor price. In McKelvey, however, the stock price was nearly 50% below the floor, so the gain was much larger. Critically, Scenario 1 illustrates that a stock price even slightly below the floor can result in gain. Advisers should also understand that under the Temp. Regs. Sec. 1.1092(b)-2T holding–period rules, the gain is generally short–term capital gain.

If the stock price remains within the trading range or exceeds the cap price, advisers should understand that this likely results in a realized loss upon a roll. If the shareholder still holds stock with unrealized gain at year end, then the straddle rules under Sec. 1092(a)(1) would likely defer recognition of the loss until such time as the remaining stock is disposed of.

VPFCs can be effective tools for clients with highly concentrated, appreciated stock positions. But, following McKelvey, tax advisers must carefully consider possible pitfalls when dealing with these complex financial instruments.

Editor

Jessica L. Jeane, J.D., is director of tax policy, national tax, with Baker Tilly in McLean, Va.

For additional information about these items, contact Jeane at Jessica.Jeane@bakertilly.com.

Contributors are members of or associated with Baker Tilly.

Baker Tilly US, LLP, and Baker Tilly Advisory Group, LP, and its subsidiary entities provide professional services through an alternative practice structure in accordance with the AICPA Code of Professional Conduct and applicable laws, regulations, and professional standards. Baker Tilly US, LLP, is a licensed independent CPA firm that provides attest services to clients. Baker Tilly Advisory Group, LP, and its subsidiary entities provide tax and business advisory services to their clients. Baker Tilly Advisory Group, LP, and its subsidiary entities are not licensed CPA firms.