- tax clinic

- TAX ACCOUNTING

Income tax purchase accounting considerations for a stock acquisition

Related

Why LIFO, why now?

Navigating safe-harbor rules for solar and wind Sec. 48E facilities

Businesses urge Treasury to destroy BOI data and finalize exemption

Editor: Jessica L. Jeane, J.D.

When it comes to purchase accounting considerations from the perspective of accounting for income tax, tax professionals look to FASB ASC Topic 805, Business Combinations, and specifically ASC Subtopic 805–740, Income Taxes. Regardless of the merger–and–acquisition environment for any given year, tax professionals will likely encounter a client that is contemplating or has recently completed a corporate sale or purchase and will have to navigate the numerous mechanics of purchase accounting. This item explores areas to consider from a perspective of accounting for income tax and the high–level mechanics within purchase accounting for a stock acquisition.

Stock or asset deal: What’s the difference?

Initially, tax professionals must understand the form of the transaction. The first question to ask is whether the transaction is structured as a purchase of shares of stock or assets of the target company. If the transaction is structured as a stock acquisition with a Sec. 338(h)(10) election, then it can be treated as a purchase of the target assets for tax purposes, which is generally favorable to the purchaser.

A stock purchase (nontaxable) is the acquisition of a target’s shares of stock, generally the ownership interest in a C corporation or an S corporation. The purchaser will obtain an outside basis in the shares of stock equal to the consideration paid but will receive carryover basis in the target’s assets — known as inside basis. Simply stated, the purchaser receives the historical tax basis in the assets of the target company and no corresponding fair market value (FMV) step–up. However, the purchaser will receive the benefit of any tax attributes of the target, such as net operating losses (NOLs) or tax credits, which may be subject to certain limitations under Secs. 382 and 383.

An asset purchase (taxable) is the acquisition of a target’s assets instead of purchasing the target’s stock. This includes a stock purchase with a Sec. 338(h)(10) election. In this scenario, the purchaser will generally receive the benefit of an FMV step–up in basis in the assets purchased equal to the consideration paid and liabilities assumed. This is favorable to the purchaser because, for example, fixed assets will be revalued under ASC Topic 805 to fair value, likely resulting in a higher basis than what the carryover tax basis would have been. After executing the purchase price allocation mechanics under Sec. 1060, any excess purchase price is allocated to identified intangibles and goodwill, which the purchaser can generally amortize over a 15–year period for tax purposes.

The income tax purchase accounting procedures for an asset deal are generally regarded as more straightforward than when analyzing a stock deal. This is because, under ASC Topic 805, the assets are purchased and revalued to FMV, typically aligning their GAAP and inside tax basis. Therefore, opening deferred tax assets (DTAs) or deferred tax liabilities (DTLs) are required to be recorded only in certain situations when a GAAP–to–tax difference exists.

When the shares of a target’s stock are acquired, the target receives a step–up in basis to FMV under ASC Topic 805; however, the tax treatment is a carryover inside tax basis. These considerations result in additional analysis to determine the opening DTAs or DTLs, which are presented on the opening balance sheet of the target company. The journal entry to book the opening DTA or DTL within the measurement period (ASC §805-10-25) is either a debit to DTA or a credit to DTL with an offset to goodwill. If the initial accounting for a business combination is incomplete by the end of the reporting period in which the combination occurs, the acquirer shall report in its financial statements provisional amounts for which accounting is incomplete (ASC ¶805-10-25-13). During the measurement period, the acquirer shall also recognize additional assets or liabilities if new information is obtained about facts and circumstances that existed as of the acquisition date that, if known, would have resulted in the recognition of those assets and liabilities as of that date (ASC ¶805-10-25-14). In general, the measurement period shall not exceed one year from the acquisition date. If an adjustment is necessary and is outside the measurement period, then in most cases the adjustment would impact the deferred tax expense or benefit on the income statement versus the balance sheet.

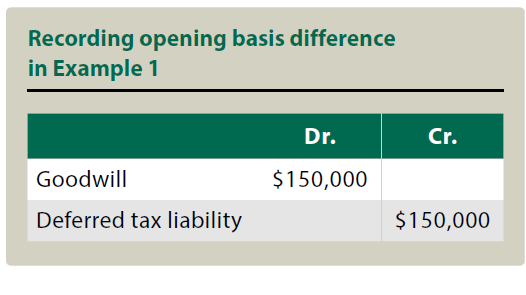

Example 1: AB Corporation acquires B Corporation in a nontaxable business combination via a stock purchase and a blended tax rate of 25%. The identifiable assets have an FMV of $700,000 (book basis) and an inside tax basis carryover of $250,000. Additionally, during the ASC Topic 805 process, it was determined that B Corporation has customer relationships valued at $150,000. The opening gross basis difference regarding the identifiable assets is the inside tax basis less FMV ($250,000 – $700,000), resulting in a $450,000 DTL. Furthermore, because the customer relationships were valued as part of the ASC Topic 805 process and had no historical inside tax basis, the opening gross DTL is $150,000. Therefore, the total opening gross DTL is $600,000. With a blended tax rate of 25%, see the chart “Recording Opening Basis Difference in Example 1” for the purchase accounting entry to record the opening basis difference (600,000 × 25%).

Component 1 and 2 goodwill in a stock deal

ASC Paragraph 805–740–25–8 guidance requires goodwill to be separated into two components as of the acquisition date: Component 1 and Component 2. Component 1 goodwill is the lesser of goodwill for financial reporting or tax–deductible goodwill. Component 2 goodwill is the remainder, if any, of goodwill for financial reporting purposes or the remainder, if any, of tax–deductible goodwill. Any difference that arises between the book and tax basis of goodwill for Component 1 in future years is a temporary difference for which a DTA or a DTL will be recognized. If Component 2 goodwill results in an excess of tax–deductible goodwill over goodwill for financial reporting, then a DTA is recognized and recorded. However, if Component 2 goodwill results in an excess of goodwill for financial reporting over tax–deductible goodwill, then no deferred taxes are recognized at the acquisition date or in future years (ASC ¶805–740–25–9).

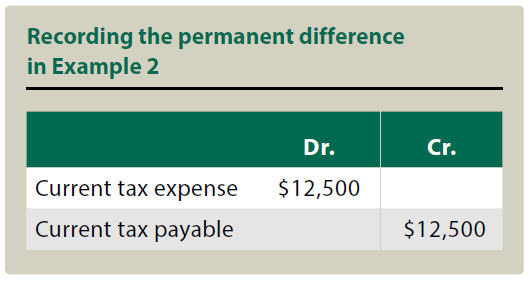

Example 2: Assume the same facts as Example 1, except that in addition to the customer relationships, goodwill of $500,000 was generated as part of the valuation process and, for financial statement purposes, AB Corporation expenses $50,000 of goodwill amortization in the post–acquisition period.

There is no tax–deductible goodwill inside tax basis carryover and no tax–deductible goodwill generated as part of the transaction. This results in Component 1 goodwill of zero and Component 2 goodwill of $500,000. Because goodwill for financial reporting is in excess of tax–deductible goodwill for Component 2 purposes, no DTL is recorded per ASC Paragraph 805–740–25–9, and the future amortization expense for financial reporting purposes will result in permanent differences for tax purposes. See the journal entry in the chart “Recording the Permanent Difference in Example 2.”

Tax attributes in a stock deal

Tax attributes refer to certain tax benefits or characteristics that can reduce a taxpayer’s liability or carry over to future tax years. In an asset acquisition, the tax attributes of the acquired company do not carry over post–transaction; however, in a stock acquisition, tax attributes will carry over and are generally available to the purchaser to reduce future taxable income or future tax liabilities and may be subject to certain limitations under Secs. 382 and 383. It is important to note that the tax attributes will generally remain with the acquired company but will be available to the group if the target joins a consolidated C corporation. Examples of tax attributes include NOLs, general business credits, and foreign tax credit carryovers. In purchase accounting, DTAs are recorded for tax attributes that carry over to the purchaser.

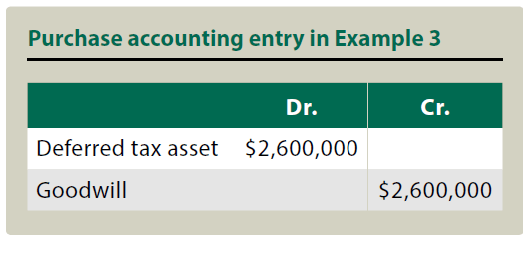

Example 3: Immediately before AB Corporation acquired B Corporation, B Corporation had a cumulative NOL carryforward of $10 million and general business credits valued at $500,000. See the chart “Purchase Accounting Entry in Example 3” for the entry that records the opening DTA for tax attribute carryovers.

In a stock purchase, tax attributes that carry over are subject to certain limitations under Secs. 382 and 383 (NOLs and credits). It is important to evaluate whether NOLs or credits will expire in future periods and if a valuation allowance against a portion or all of the tax attributes may be necessary, depending on the scheduling exercise.

Valuation allowance considerations

A valuation allowance is the portion of a DTA for which it is more likely than not that a future tax benefit will not be realized. Per ASC Paragraph 805–740–25–3, an acquirer shall assess the need for a valuation allowance as of the acquisition date for an acquired entity’s DTA in accordance with ASC Subtopic 740–10. Typically, the first step in assessing the need for a valuation allowance is to conduct the cumulative–loss test, which looks at the company’s pretax book income or loss over a three–year period. A cumulative loss in recent years is a significant piece of negative evidence that is difficult to overcome (ASC ¶740–10–30–23).

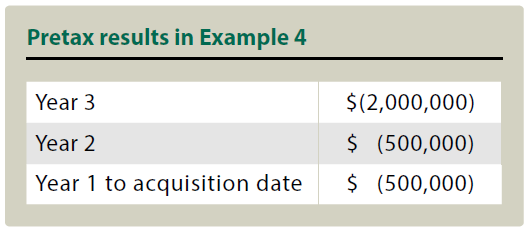

Example 4: C corporation acquires D corporation for a purchase price of $1 million, and through the valuation process, it is determined that the assigned value of the net assets acquired is also $1 million. The inside tax basis for the assets acquired is $1 million. D Corporation also has an NOL carryforward of $2 million. Tax law limits the use of NOLs to subsequent taxable income of the group. The acquired post-Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) (P.L. 115–97)-generated NOLs are limited to 80% of future taxable income by Sec. 382.

D Corporation’s pretax results for the two preceding years and the results up to the acquisition date are as shown in the chart “Pretax Results in Example 4.”

Based on the assessment of all evidence available at the date of the acquisition, management concludes that a valuation allowance is needed as of the acquisition date for the entire amount of the DTA related to the acquired NOLs.

Transaction costs considerations

From a purchase accounting perspective, the analysis of buy–side transaction costs in a nontaxable transaction can be very complex. Transaction costs incurred by the acquirer are typically expensed for financial statement purposes. However, for tax purposes, the tax effects associated with the transaction costs must be accounted for in accordance with the nature of the costs incurred (legal fees, accounting fees, investment banking fees, valuation, etc.) and the type of deal. In a stock transaction, it is common for a substantial amount of the costs to be capitalized to the outside basis of the stock acquired, by way of a permanent difference, thus impacting the effective tax rate for the acquisition period. Certain compensation–related costs may be currently deductible. It could also be beneficial to consider the Rev. Proc. 2011–29 safe–harbor election for success–based fees, which allows for 70% deductibility of the success–based fees and capitalization of the remaining 30%.

Other considerations

New income tax jurisdictions: When acquiring a new company or companies, it is expected for the purchaser to analyze potential new tax jurisdictions resulting in a larger state (or foreign) tax footprint. When this occurs, it is important to consider the new jurisdictions in the blended rate. Any tax attributes related to each jurisdiction should also be evaluated when setting up opening deferred balances.

Contingent consideration/earnouts: In a stock transaction, the inside tax basis in the contingent consideration will generally equal the financial reporting basis. Upon analysis, should the inside tax basis be either greater or less than the financial reporting basis, then further analysis is necessary to determine the need for a DTA or a DTL (see ASC ¶¶740-30-25-9, 740-10-25-3(a), and 740-30-25-7). If there is no difference between book and inside tax basis, then any settlement of contingent consideration will increase the inside tax basis of the stock acquired. Additionally, any future remeasurement of the contingent consideration (either an increase or a decrease in value) will result in a permanent difference for tax purposes, impacting the effective tax rate.

Editor

Jessica L. Jeane, J.D., is director of tax policy, national tax, with Baker Tilly in McLean, Va.

For additional information about these items, contact Jeane at Jessica.Jeane@bakertilly.com.

Contributors are members of or associated with Baker Tilly.

Baker Tilly US, LLP, and Baker Tilly Advisory Group, LP, and its subsidiary entities provide professional services through an alternative practice structure in accordance with the AICPA Code of Professional Conduct and applicable laws, regulations, and professional standards. Baker Tilly US, LLP, is a licensed independent CPA firm that provides attest services to clients. Baker Tilly Advisory Group, LP, and its subsidiary entities provide tax and business advisory services to their clients. Baker Tilly Advisory Group, LP, and its subsidiary entities are not licensed CPA firms.