- tax clinic

- GAINS & LOSSES

Like-kind exchanges of real estate: Building on the basics

Related

Murrin and Zuch provide insight into the limits of taxpayers’ rights

IRS generally eliminates 5% safe harbor for determining beginning of construction for wind and solar projects

IRS rules that community trust and affiliated nonprofit corporation can file a single Form 990

TOPICS

Editor: Rochelle Hodes, J.D., LL.M.

Like–kind exchanges are a valuable tool for deferring gain or loss in real estate transactions. While a like–kind exchange of one qualifying property for another qualifying property is straightforward, it often is not possible in the real world. This item addresses how to achieve like–kind treatment in more complex transactions, such as those involving exchanges of multiple properties, reverse exchanges, and straddle exchanges.

Background

Sec. 1031(a)(1) generally provides that no gain or loss is recognized on the exchange of real property held for productive use in a trade or business, or for investment, if such property is exchanged solely for real property of like kind that is also to be held either for productive use in a trade or business or for investment. Sec. 1031 also provides identification and exchange–period requirements that must be met, including:

- Replacement property must be identified within the 45-day identification period;

- Replacement property must be received within the 180-day exchange period; and

- The taxpayer cannot be in actual or constructive receipt of money or property. Use of a qualified intermediary (QI) or a qualified escrow agent can alleviate this burden (Regs. Sec. 1.1031(k)-1; see also Robirds and Blaivas, “Like-Kind Exchanges of Real Estate: Back to Basics,” 55-9 The Tax Adviser 11 (September 2024)).

Many real estate transactions, such as the sale of a large apartment complex, involve real property with a substantial personal-property component. Regs. Sec. 1.1031(k)-1(g)(7)(iii)(B) provides a safe harbor for personal property if the aggregate fair market value (FMV) of the personal property transferred with the real property does not exceed 15% of the aggregate FMV of the replacement real property or properties received in the exchange. Thus, as long as the FMV of the personal property does not exceed 15% of the total FMV of the purchase price, the personal property does not cause the real estate to be ineligible for like-kind exchange treatment.

Multiproperty exchanges

A taxpayer may want to invest in property with a lower value than the property being exchanged, requiring the acquisition of two or more replacement properties in order to be able to take full advantage of the benefits of gain deferral provided by Sec. 1031. Conversely, a taxpayer may be selling multiple properties in order to invest in a bigger property or in other multiple properties.

The exchange of one property for multiple properties is treated similarly to a one–for–one exchange. The same identification period and timing rules apply, triggered by the initial sale. The additional complexity is more of a logistical concern because the property purchases need to be completed within the 180–day window.

When calculating boot and determining whether the exchange allows a complete deferral of gain, the purchase price, exchange expenses, and debt of the properties are included in the calculation.

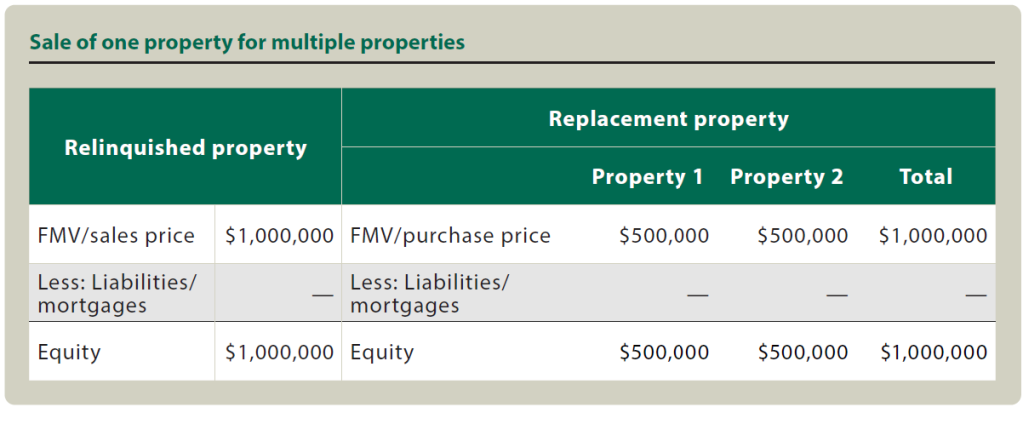

This aspect of a multiproperty exchange is relatively intuitive. The bigger issue is the allocation of the carryover basis to these new properties (see the chart “Sale of One Property for Multiple Properties,” below).

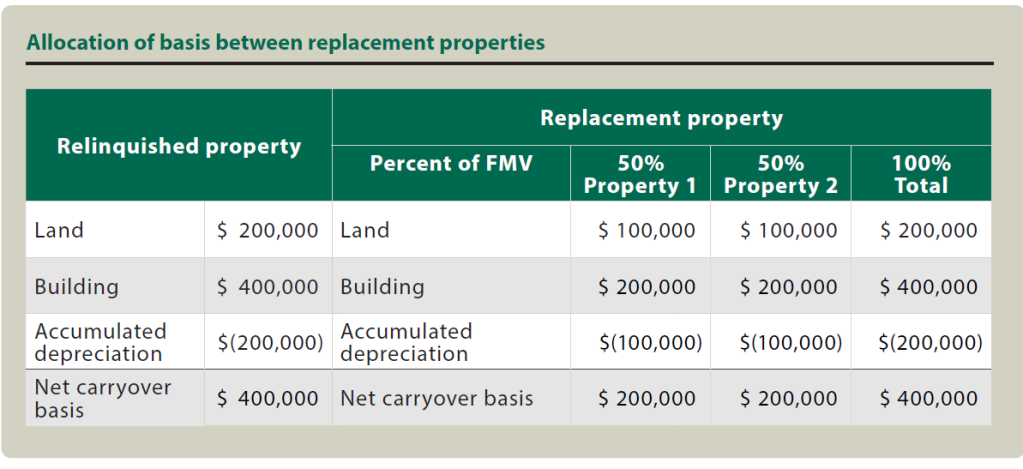

Assume that the basis in the relinquished property is $200,000 for land and $400,000 for a building, with $200,000 of accumulated depreciation. The total net tax basis is $400,000. That basis must then be allocated between the two replacement properties.

Under Regs. Sec. 1.1031(j)-1(c), the basis of the relinquished property is allocated to the replacement properties in proportion to their relative FMVs. Since the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, P.L. 115-97, limited Sec. 1031 treatment to real estate for exchanges completed after 2017, the use of “exchange groups” has largely become irrelevant.

Therefore, in the example, the basis allocation is shown in the chart “Allocation of Basis Between Replacement Properties” below.

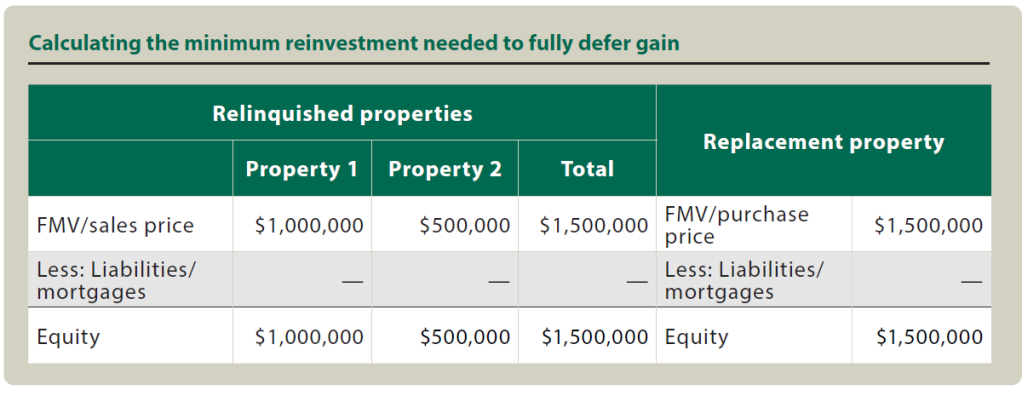

Sale of multiple properties, purchase of one property: Although it is less common, some taxpayers may sell multiple properties to simplify a real estate portfolio or acquire a single, high–value property.

When selling multiple properties, the FMV, exchange expenses, and liabilities relieved of all properties sold as part of the exchange are taken into account to determine the minimum amount required to be reinvested into the replacement property to achieve complete deferral of the gain (see the chart “Calculating the Minimum Reinvestment Needed to Fully Defer Gain,” below).

The biggest issue in multiproperty sales is timing. The 180–day period starts when the first property is sold, so if subsequent sales and purchase of the target properties are not completed in time, there could be a failed exchange or only a partial deferral.

Reverse exchanges

A traditional, or “forward” like–kind exchange generally involves first entering into a contract to sell a relinquished property, followed by the identification of, and entering into a contract to acquire, the replacement property. However, the taxpayer might have to acquire the replacement property before the relinquished property is sold (for example, due to seller constraints). To accomplish this, a taxpayer engages in a “reverse” exchange or a “parking” arrangement.

In a reverse exchange, an accommodation party, not the taxpayer, acquires and holds the replacement property, generally until the relinquished property is sold. For a reverse exchange to be respected, the accommodation party must have sufficient benefits and burdens of ownership to be considered the owner of the replacement property for tax purposes. Aside from the subjective nature of such a determination, satisfying this requirement can also be difficult from a purely practical perspective, given that accommodation parties usually are not in the business of taking on the risks of real estate ownership.

To address these concerns, the IRS provided a safe harbor for reverse like–kind exchanges in Rev. Proc. 2000–37, which generally provides that an accommodation party will be treated as the owner of the replacement property for tax purposes if the following requirements are satisfied:

- The accommodation party holding title to the replacement property is an exchange accommodation titleholder (EAT) — generally, a person who is neither the taxpayer nor a “disqualified person” that is subject to federal income tax. A disqualified person would be an agent of the taxpayer, which generally includes the taxpayer’s employee, attorney, accountant, or real estate agent or broker.

- Within 45 days of the acquisition of the replacement property by the EAT, the taxpayer identifies the relinquished property.

- The exchange is completed no later than 180 days after the transfer of the replacement property by the EAT.

Straddle transactions

To obtain deferral under Sec. 1031, the exchange must be completed within 180 days. In certain instances, this may straddle two tax periods. An exchange entered in the last half of the year could potentially be completed in the subsequent tax year. Using a QI improves the chances of identifying replacement property before the end of the tax year. However, if no replacement property is acquired by year end of the tax year in which the relinquished property was sold and the taxpayer is not entitled to receive the sales proceeds from the QI before the end of the tax year, the transaction should be treated as an installment sale, and the gain is recognized in the following year when proceeds are received.

Note: Depreciation recapture treated as ordinary income is not eligible for installment treatment. In addition, depending on when the 180–day exchange period begins, the taxpayer may also need to file for an extension to report a transaction that begins in year 1 and concludes in year 2.

The difference in reporting is as follows:

- Exchange starts in year 1 and fails in year 2:

- Form 8824, Like-Kind Exchanges, is filed in year 1 to report the deferral.

- Form 6252, Installment Sale Income, is filed in year 1 to report zero payments received.

- Form 6252 is filed again in year 2 to report the installment sale gain.

- Exchange starts in year 1 and is completed in year 2:

- Form 8824 is filed in year 1 to report the completed like-kind exchange.

Real-world applications

Although Sec. 1031 requires strict compliance, it can accommodate the complexities of real estate transactions. Like–kind exchanges remain a powerful tax–deferral tool, even when the ideal fact pattern is not present. And even when Sec. 1031 treatment is unavailable, other deferral opportunities may exist.

Editor

Rochelle Hodes, J.D., LL.M., is principal with Washington National Tax, Crowe LLP, in Washington, D.C.

For additional information about these items, contact Hodes at Rochelle.Hodes@crowe.com.

Contributors are members of or associated with Crowe LLP.