- feature

- ESTATES, TRUSTS & GIFTS

Trust distributions in kind and the Sec. 643(e)(3) election

Related

Estate of McKelvey highlights potential tax pitfalls of variable prepaid forward contracts

Recent developments in estate planning

Guidance on research or experimental expenditures under H.R. 1 issued

In-kind distributions, where a trust transfers property instead of cash, are common in practice but far from straightforward. Trustees may use them for many reasons, such as illiquidity, a beneficiary’s preference to keep an asset, or unfavorable market conditions. From a tax standpoint, the key question to consider is whether to make a Sec. 643(e)(3) election, a little–known but powerful tool that can dramatically change the outcome for both the trust and its beneficiaries.

The Sec. 643(e)(3) election allows the fiduciary to treat an in–kind distribution as if the trust or estate had sold the property to the beneficiary at its fair market value (FMV) at the time of distribution, potentially triggering a taxable gain for the entity and giving the beneficiary a stepped–up basis in the property equal to its FMV.

Trust taxation generally

To understand the implications of in–kind distributions and the Sec. 643(e)(3) election, it helps to first review how income is taxed at the trust and beneficiary levels.

One of the unique features of trust taxation is the income distribution deduction (IDD). When a trust makes a distribution to a beneficiary, the related taxable income is carried out and taxed to the beneficiary, while the trust receives a matching deduction. This prevents double taxation. However, because distributions can exceed taxable income, there is a cap on how much of a distribution can be deducted by a trust and passed through as income to beneficiaries. This cap is known as distributable net income (DNI).

Put simply, DNI represents the trust’s taxable income before the IDD, adjusted to remove items that are treated as part of the trust’s corpus rather than current income. Capital gains are a particularly tricky item: They are often allocated to corpus and thus excluded from DNI, but whether they count as corpus or income depends on the trust document and governing state and local law. In short, DNI sets both the maximum taxable income that can be passed out to beneficiaries and the maximum deduction the trust can claim.

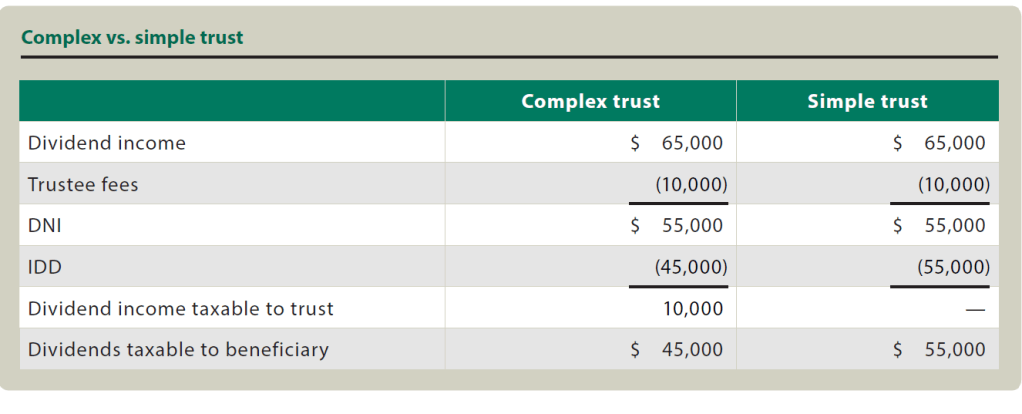

Example 1: C is the trustee of a trust for the benefit of L. The trust document requires that 20% of the trust assets be distributed to L when she turns 25. If the trust is worth $225,000 at that time, $45,000 of distributions would be required during the year. Suppose further that, during the same year, the trust earned $65,000 of dividend income and incurred $10,000 of trustee fees. After paying expenses, the DNI would be $55,000. When the trust distributes $45,000 to L, it receives an IDD for the same amount. L will receive a Schedule K–1 (Form 1041), Beneficiary’s Share of Income, Deductions, Credits, etc., reporting $45,000 of dividend income, while the trust is taxed on the remaining $10,000 of dividend income ($65,000 of dividends – $10,000 of trustee fees – $45,000 IDD).

It is important to note that this outcome applies only to complex trusts. Simple trusts work differently because their required distributions are based on trust accounting income rather than DNI. Using the same facts as Example 1, a simple trust would have to distribute all $55,000 of income. The beneficiary’s Schedule K–1 would report $55,000 of dividends, and the trust itself would have no taxable income (see the table “Complex vs. Simple Trust”). Also, a Sec. 643(e)(3) election is not available for simple trusts — all the remaining examples focus on complex trusts only.

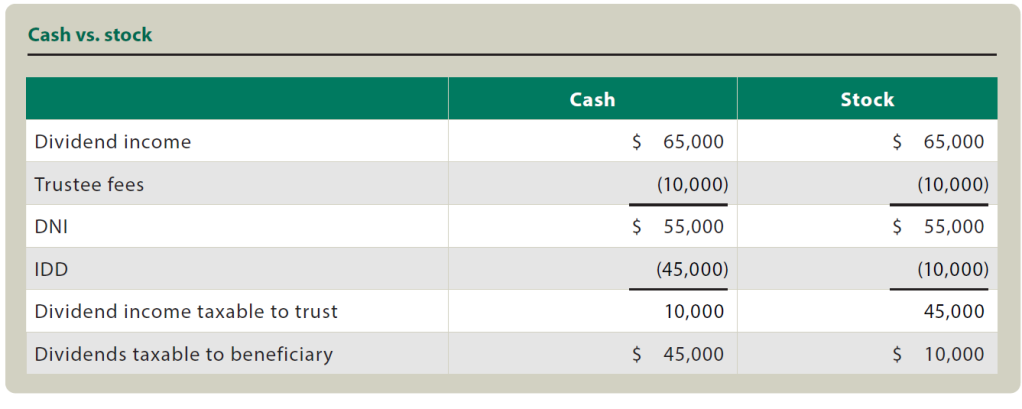

Now revisit Example 1, but this time C distributes stock with a basis of $10,000 and an FMV of $45,000 instead of cash. Without a Sec. 643(e)(3) election, in–kind distributions are valued at the lower of cost basis or FMV.1 That rule also controls both the IDD and the amount of income taxable to the beneficiary.

In this case, the IDD is limited to $10,000 (the stock’s basis), not $45,000 (its FMV). As a result, the trust is left with $45,000 of taxable dividend income: $65,000 of dividends – $10,000 of trustee fees – $10,000 IDD. L’s Schedule K–1 reflects only $10,000 of dividends, even though she received property worth $45,000 (see the table “Cash vs. Stock”).

California throwback rule

As the stock distribution example above illustrates, an in–kind distribution can reduce the IDD while still giving the beneficiary the same economic value. This feature can be especially important in states like California that impose a “throwback tax” on accumulated income.

Example 2: With the same other facts as in Example 1, suppose L is a California resident and the trust is domiciled in Nevada. Until now, L has been a contingent beneficiary because C had full discretion over distributions. As a result, the trust never filed a California tax return and has never paid California tax on its income. Once L turns 25 and becomes entitled to a $45,000 distribution, she becomes a noncontingent beneficiary, triggering a California filing requirement.

Here is where the throwback rule comes into play: If a noncontingent California beneficiary receives distributions in excess of the current–year DNI, the excess is treated as a distribution of accumulated income, which is all historical income that was not previously taxed by California when the beneficiary was a contingent beneficiary.2 As a noncontingent beneficiary, L will now be subject to California tax on (1) the current year’s taxable income and (2) the accumulated income distributed but not previously taxed by California.

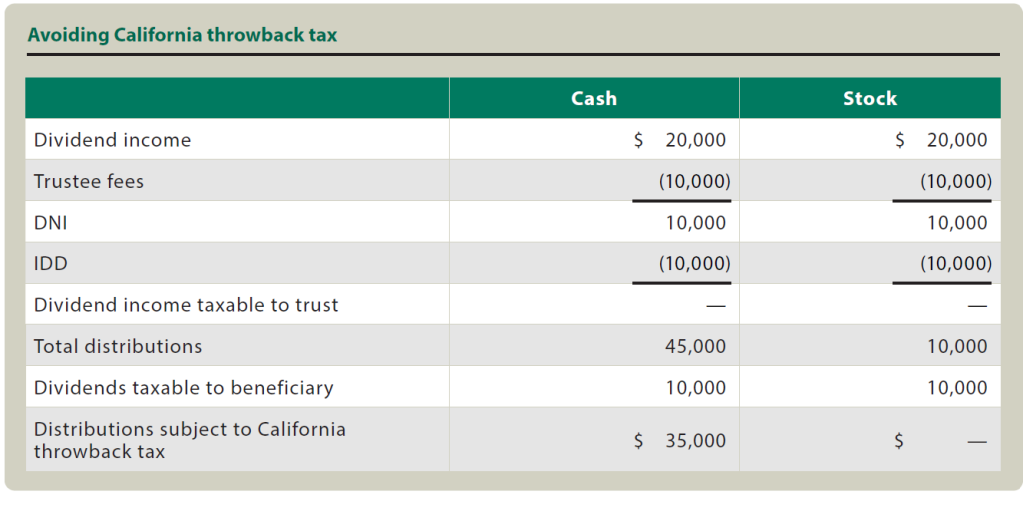

Example 3: To illustrate, assume that the trust only earned $20,000 of dividend income during the year. After trustee fees, the DNI is $10,000, and the IDD is also limited to $10,000. If C distributes $45,000 in cash, $35,000 of that distribution exceeds current–year DNI. For federal purposes, the excess is treated as a distribution of corpus and has no tax effect. For California purposes, however, the $35,000 is considered to be distributed from accumulated income and becomes subject to the throwback tax, along with the complicated calculations that go with it.

By distributing stock instead, the trust can limit the IDD to the stock’s $10,000 basis. L still receives $45,000 of value, but for tax purposes, only $10,000 counts toward DNI — because in–kind distributions are recognized at the lower of cost or FMV. That keeps the distribution within current–year income, so none of it is treated as accumulated income. In this way, the trust avoids triggering the California throwback tax entirely (see the table “Avoiding California Throwback Tax”).

The Sec. 643(e)(3) election: Potential pitfalls

The prior examples show how distributing stock at its $10,000 basis limited the IDD, reduced the amount reported to L, and even helped avoid California’s throwback tax. But what if the trustee instead makes a Sec. 643(e)(3) election?

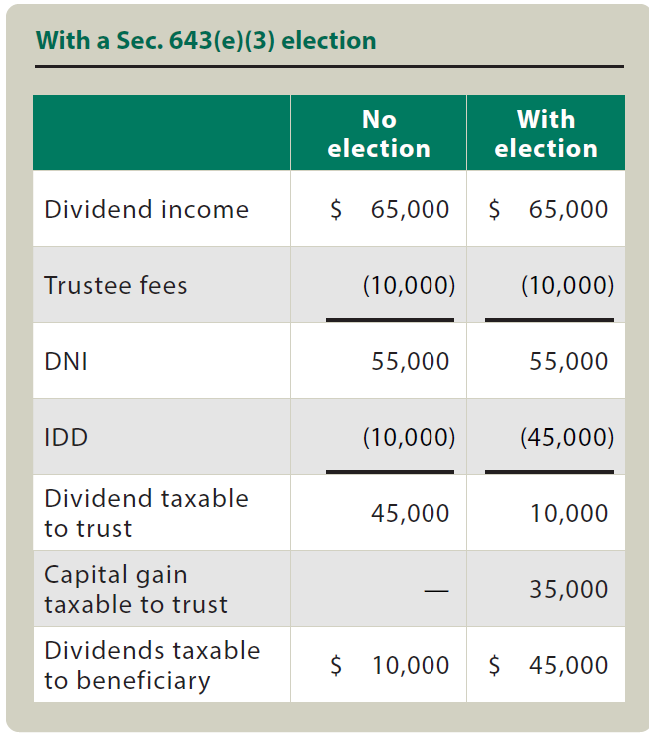

Example 4: With the election, the trust treats the in–kind distribution as if the stock were sold to L for its FMV of $45,000. That means the trust recognizes a $35,000 gain ($45,000 FMV – $10,000 basis). For purposes of the IDD, the amount is equal to the property’s basis plus the recognized gain: in this case, $45,000 ($10,000 basis plus $35,000 gain). L’s Schedule K–1 would report $45,000 of dividend income, while the trust would be taxed on the remaining $10,000 ($65,000 of dividends – $10,000 trustee fees – $45,000 IDD) (see the table “With a Sec. 643(e)(3) Election”).

Does this look familiar? With the Sec. 643(e)(3) election, the tax result mirrors a cash distribution: L reports $45,000 of dividend income, and the trust is taxed on $10,000 of dividend income. But there is a critical difference: The trust has now recognized $35,000 of capital gain, and L holds stock with a stepped–up $45,000 basis. Earlier, distributing the stock at its $10,000 basis helped avoid the California throwback tax; that benefit disappears once the election forces recognition at FMV. The election also accelerates gain that otherwise would not be taxed until the stock is sold. Furthermore, if L planned to keep the stock until death, she would have eventually received a basis step–up at that time without any current tax cost.

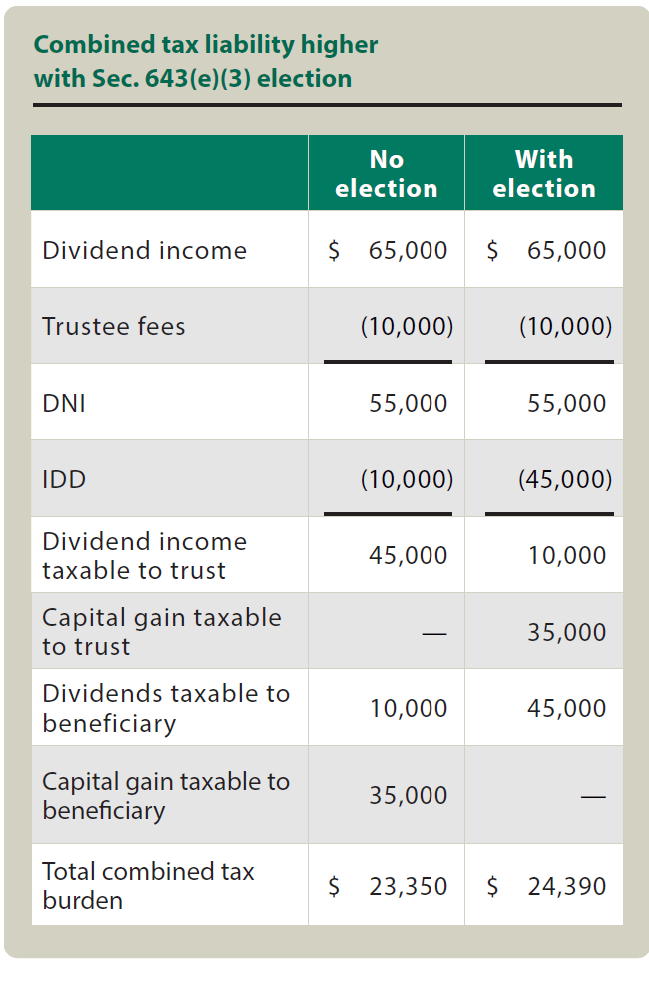

Let’s give C the benefit of the doubt and assume L planned to sell the stock immediately anyway, so that the gain would have been recognized in the current year regardless. Even then, the election still does not improve the tax outcome. Total taxable income between the trust and L is the same $90,000 under either approach, but the difference lies in who pays the tax — and that matters. Trusts reach the top federal income tax rate at $15,650 of taxable income in 2025, while individuals do not reach the top rate until $626,350 single or $751,600 married filing jointly.3 Recognizing the gain inside the trust generally results in more of the income being taxed at the highest rates, making the election unfavorable in many cases.

Example 5: Assume L is in the 35% marginal bracket before the distribution and her capital gain rate is 15%. Without the election, L pays tax on both the $35,000 capital gain and $10,000 of dividend income ([$35,000 × 15%] + [$10,000 × 35%] = $8,750), while the trust pays tax only on its $45,000 of dividends ($14,600, based on the 2025 tax brackets), for a combined liability of $23,350. With the election, the trust pays $8,640 of tax on $35,000 of capital gain and $10,000 of dividend income (based on the brackets), while L pays $15,750 of tax on the $45,000 of dividend income passed out to her ($45,000 × 35%), for a combined liability of $24,390 (see the table “Combined Tax Liability Higher With Sec. 643(e)(3) Election”).

In this scenario, the better tax answer is not to make the election, as it increases the overall tax burden by $1,040. The disadvantage of making the election is reduced if L’s income falls in lower marginal brackets, and it could be further reduced if she had significant losses or net operating losses (NOLs) that could have offset the gain had it been recognized at her level rather than at the trust’s.

Potential opportunities with the election

Now that we have reviewed some of the pitfalls that C — and C’s CPA — could fall victim to, it’s important to remember that the Sec. 643(e)(3) election can also create opportunities. Whether it is advantageous often depends on where losses, carryovers, or other tax attributes are available: in the trust or in the hands of the beneficiary.

Capital losses

Suppose the trust had a $45,000 capital loss carryover from the prior year. By making the Sec. 643(e)(3) election, the $35,000 gain triggered on the stock distribution can be fully offset against that loss. Instead of being limited to the $3,000 annual deduction that applies to individuals,4 the trust uses most of the loss immediately, leaving only $7,000 to carry forward. L receives stock with a stepped–up basis of $45,000, and no additional tax is paid.

On the other hand, if the beneficiary is known to have unused capital losses, distributing the appreciated property without making the election may be the better approach. In that scenario, L would later recognize gain herself and could apply her own capital losses against it.

Recharacterization of income

Even when the total taxable income between the beneficiary and the trust is the same, a Sec. 643(e)(3) election can change the character of that income in ways that may be useful for planning. For example, in the scenario of Example 5, the election recharacterizes what would have been $45,000 of dividend income at the trust level to $35,000 of capital gain and $10,000 of dividend income, while recharacterizing the $35,000 of capital gain and $10,000 of dividend income at L’s level to $45,000 of dividend income.

This recharacterization can be valuable under the right circumstances because who reports the income — and in what form — can affect the overall tax result. If the goal is to preserve trust assets, shifting part of the tax burden to L may be desirable, since it reduces the amount of tax paid directly from the trust, thus keeping more assets in the trust. Similarly, if L has NOLs available, shifting ordinary income from the trust to her could be more tax–efficient.

Depreciable property

The examples so far have involved investment assets, but a Sec. 643(e)(3) election can also create opportunities when a trust holds depreciable property.

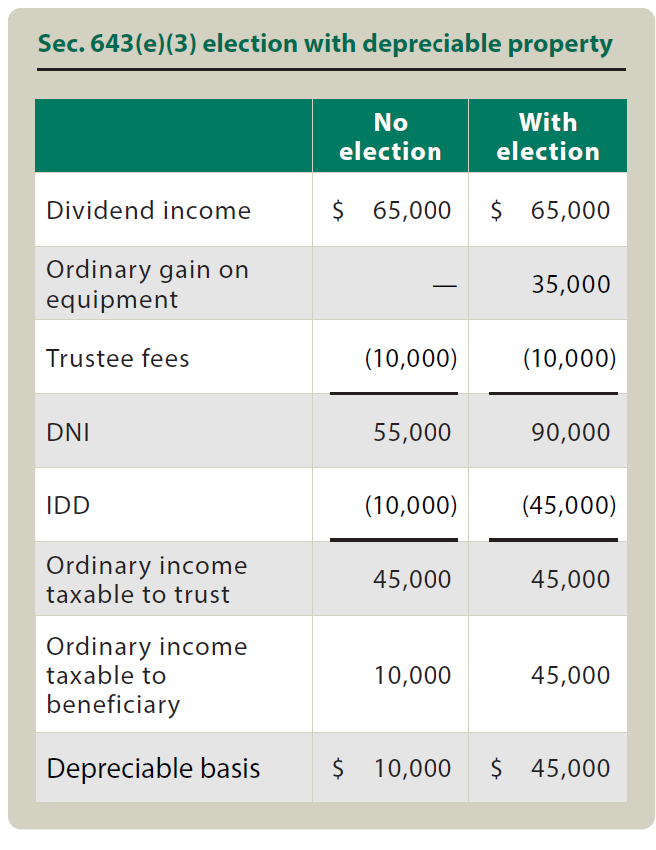

Example 6: To keep the numbers consistent with the earlier scenarios, suppose L’s trust instead holds equipment with an FMV of $45,000 and a basis of $10,000 that she plans to use in her business. If C distributes the equipment to L and makes the election, L takes a $45,000 basis and can depreciate that amount over five years (see the table “Sec. 643(e)(3) Election With Depreciable Property”).

With careful planning, the distribution can be timed to maximize the tax benefit. For instance, if it occurs in a year when L’s income is relatively low but expected to increase over the next several years, the larger depreciation deductions in those higher–income years may outweigh the immediate tax cost of recognizing more income in the year of distribution.

For the trust, the result is the same either way because gain realized on a sale or exchange between related parties of depreciable property (including a distribution of depreciable property from a trust to a beneficiary) is treated as ordinary income rather than as capital gain.5 The principal benefit lies with the beneficiary, who receives additional depreciation deductions in future years; the trust itself essentially sees no change in outcome compared with a nonelection.

Requirements to make the election

- Trust type:The trust must be a complex trust; the election is not available for simple trusts.

- Distribution type:It applies only to discretionary (Tier 2) distributions. A pecuniary bequest (a fixed dollar amount or specific property designated in the trust document or will) is automatically treated as sold to the beneficiary upon distribution and thus is not eligible for the election.6

- All or nothing:The election applies to all in-kind distributions made during the tax year; the trustee cannot pick and choose which assets it covers.7

- Annual choice:The election can be made on a year-by-year basis. Once made, it can be revoked only with the IRS’s consent.

- Loss property:The election provides no benefit when property is in a loss position because, under Sec. 267(a), losses on sales between related parties are not recognized. Therefore, a trust that distributes property with an FMV less than its basis to a beneficiary and makes the Sec. 643(e)(3) election will not be able to recognize the loss.

- Return filing:The election must be made on a timely filed Form 1041, U.S. Income Tax Return for Estates and Trusts (including extensions).8 To make the election, the fiduciary reports the transaction on Form 8949, Sales and Other Dispositions of Capital Assets, and Form 1041, Schedule D, Capital Gains and Losses, and checks the box on line 7 in the “Other Information” section of Form 1041, Schedule G, Tax Computation and Payments. No separate statement is required to be attached.

A word of caution

A Sec. 643(e)(3) election can affect beneficiaries unevenly, so fiduciaries need to consider the impact when multiple beneficiaries are involved. For example, one beneficiary might receive appreciated property while another receives cash. If the election is made, the trust recognizes gain on a deemed sale of the property (as required by the election), which reduces the overall corpus available for distribution. In effect, the cash beneficiary bears part of the tax cost of the other beneficiary’s stepped–up basis.

If equal treatment among beneficiaries is the goal, the trustee may need to adjust the amount distributed to the cash beneficiary to account for the additional tax burden created by the election.

Final thoughts

The scenarios in this article are not exhaustive, but they highlight some of the key considerations when deciding whether to distribute property in kind and whether to make a Sec. 643(e)(3) election. The outcomes can vary widely depending on the assets involved, the trust’s tax attributes, and the beneficiary’s circumstances.

For fiduciaries and their advisers, the takeaway is clear: A Sec. 643(e)(3) election is neither automatically good nor automatically bad. It can create traps if made without careful analysis, but it can also provide valuable planning opportunities when the facts align. Understanding both the risks and the planning opportunities is essential to helping clients achieve the best results.

Footnotes

1Sec. 643(e)(2).

2Cal. Rev. & Tax. Code §17745.

3Sec. 1(j)(2); Rev. Proc. 2024-40, §2.01.

4Sec. 1211(b).

5Sec. 1239.

6Sec. 643(e)(4).

7Sec. 643(e)(3)(B).

8Id.

Contributor

Daniel Jourdier, CPA, is a tax manager with Navolio & Tallman LLP in Walnut Creek, Calif. For more information about this article, contact thetaxadviser@aicpa.org.

MEMBER RESOURCES

Tax Section resources

Estate and Trust Engagement Letter — Form 1041

Estate and Trust Tax Return Organizer — Form 1041

Estate and Trust Income Tax Return Checklist — Form 1041 (Long)

Estate Tax Return Organizer — Form 706

Webcast

“Estate & Trust Primer — Tax Staff Essentials,” Feb. 11, 1–5 p.m. ET

CPE self-study

Estate & Trust Primer — Tax Staff Essentials

For more information or to make a purchase, visit aicpa-cima.com/cpe-learning or call 888-777-7077.