- newsletter

- TAX INSIDER

Offer-in-compromise scams expected to increase

What can be done about predatory firms that make exaggerated promises of being able to settle tax debt? A recession provides fertile ground for their scams.

Please note: This item is from our archives and was published in 2020. It is provided for historical reference. The content may be out of date and links may no longer function.

Related

Murrin and Zuch provide insight into the limits of taxpayers’ rights

IRS generally eliminates 5% safe harbor for determining beginning of construction for wind and solar projects

IRS rules that community trust and affiliated nonprofit corporation can file a single Form 990

Predatory firms that exaggerate their ability to help taxpayers settle their tax debt have proliferated in recent years, using increasingly sophisticated methods in their misleading marketing materials. This summer, for the first time, the IRS included these shady operators in its annual Dirty Dozen list of tax scams.

While many tax debt resolution businesses are legitimate, others cross ethical boundaries, harming vulnerable taxpayers and spreading unrealistic expectations about settling tax debt for less than the face amount owed.

“It’s a real problem,” said Chastity Wilson, CPA, J.D., LL.M., of CLA (CliftonLarsonAllen LLP), noting that predatory tax debt resolution businesses have been an increasing phenomenon over the last decade or so. “I’ve seen it just become prolific.” Wilson is the immediate past chair of the AICPA’s IRS Advocacy & Relations Committee.

Predatory debt relief firms often lure desperate, financially strapped taxpayers through precision-targeted direct-mail campaigns and are “really not following through with the services that they promise they’re going to provide, and I think that’s where it’s just a real shame,” Wilson said in an interview with Tax Insider.

The several thousand dollars they charge is unjustifiably high, Wilson said, especially because the IRS generally uses a straightforward mathematical calculation in deciding whether to accept an offer in compromise (OIC). Wilson has heard of tax debt relief firms asking for $25,000 or more in fees.

The problem will probably grow worse during the COVID-19 recession as a greater number of taxpayers struggle financially and face possible tax troubles. The recession, in fact, is the reason why the IRS added “offer-in-compromise mills” (OIC mills) to its annual Dirty Dozen list, according to a statement the IRS media office emailed to Tax Insider.

Crossing the line

Desperate clients often give credence to OIC mills’ media advertisements promising miraculous tax debt relief, “so when you’re telling them the reality of it, they don’t necessarily believe you,” Wilson noted. To help clients understand the true odds of successfully compromising tax debt, Wilson shows them statistics in the IRS Data Book. In 2019, for instance, the Service accepted only about one out of every three OICs (17,890 of 54,225) that were submitted.

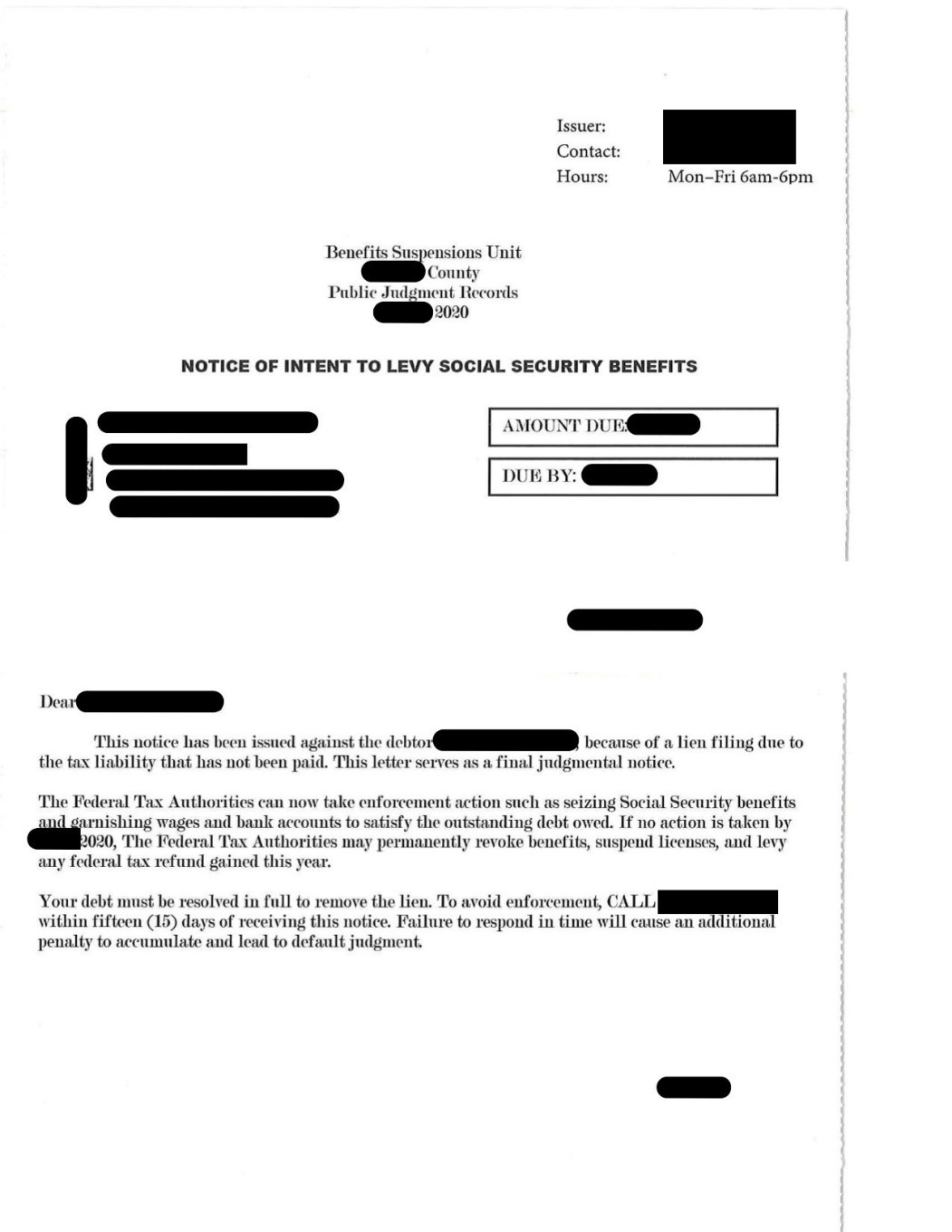

Many OIC mills use sophisticated marketing techniques such as monitoring public records for tax lien information and then mailing the affected taxpayers misleading letters that warn of drastic consequences if the person fails to contact an “800” phone number. Some of the solicitation letters mislead recipients by uncannily resembling official IRS notices. “It is just insane how much these look like real IRS notices,” Wilson said. Here is an example of one of these letters:

Is there a solution?

One possible mechanism for cracking down on predatory tax debt resolution businesses is Treasury Circular 230, Regulations Governing Practice Before the Internal Revenue Service (31 C.F.R. Part 10). Tax debt resolution firms that are run by CPAs, enrolled agents, and other Circular 230 practitioners must abide by the circular’s solicitation and other rules.

But the IRS needs resources to be able to enforce its rules, and the Office of Professional Responsibility has had significant staff cuts in recent years, Wilson said.

Circular 230 provides, among other things, that a practitioner may not “in any way use or participate in” public communications or private solicitations containing false, fraudulent, coercive, misleading, or deceptive statements or claims. The circular also imposes restrictions on associating with any person or entity who “obtains clients … in a manner forbidden under this section” (Sections 10.30(a) and (d)).

Circular 230 is not the only available enforcement mechanism, however. Many individuals who manage or work for OIC mills are bound by ethical standards imposed by state boards of accountancy and other licensing bodies. In addition, OIC mills’ activities may violate state consumer protection laws. Indeed, much of the enforcement activity in this area has been by state attorneys general; the Federal Trade Commission sometimes gets involved also. But while government attorneys are occasionally able to force an OIC mill into compliance, or into bankruptcy, new OIC mills seem to spring up continually. These companies flourish most during an economic downturn.

While more enforcement is needed, taxpayers should remember “buyer beware” too. The IRS reminds taxpayers to be cautious about whom they hire and to carefully “avoid giving their hard-earned money to the few bad apples in the industry.”

Offers in compromise: In general

Strict rules govern when the IRS can compromise tax debt. In most cases, the IRS will reject an OIC that is less than what it calls the “reasonable collection potential” (RCP), which is a measure of the taxpayer’s ability to pay. RCP includes the value of the taxpayer’s assets, such as bank accounts, motor vehicles, and real property. It also includes anticipated future income minus certain amounts allowed for basic living expenses. The IRS has a limited amount of wiggle room to depart from the RCP test in hardship cases (see Regs. Sec. 301.7122-1(c)(3)(iii)). To submit an OIC, use Form 656, Offer in Compromise.

While most OICs are based on the taxpayer’s inability to pay the tax debt (doubt as to collectibility), an OIC can also be used when there is a genuine dispute whether the taxpayer in fact owes the taxes (doubt as to liability). Because other procedures are available to dispute tax liability, taxpayers should rarely need to rely on an OIC to do so. In appropriate situations, though, they can use Form 656−L, Offer in Compromise (Doubt as to Liability). For more information about OICs, see IRS.gov.

— Dave Strausfeld, J.D., is a Tax Adviser senior editor. To comment on this article or to suggest an idea for another article, contact him at David.Strausfeld@aicpa-cima.com.