- column

- CAMPUS TO CLIENTS

Applying updated ASC Topic 740 requirements for the income tax footnote

Case studies provide practice in applying the new FASB tax accounting standards for public business entities.

Related

IRS removes associated-property rule from interest capitalization regulations

Why LIFO, why now?

Digital asset transactions: Broker reporting, amount realized, and basis

TOPICS

Editor: Annette Nellen, Esq., CPA, CGMA

In an effort to increase the transparency and usefulness of the income tax footnote disclosures, FASB promulgated Accounting Standards Update (ASU) No. 2023–09, Improvements to Income Tax Disclosures, in December 2023. In the ASU, FASB issued amendments to ASC Topic 740, Income Taxes, to increase disclosure requirements for multiple components of the income tax provision footnote. The changes are effective for tax years beginning after Dec. 15, 2024, for all public business entities (PBEs). This column reviews several of these provisions for PBEs, and the downloadable Excel file provides case studies for readers to gain practice in applying the updated requirements while crafting the effective tax rate (ETR) reconciliation and presenting income tax expense in compliance with these new standards.

Public business entities

ASC Topic 740 formerly had one set of reporting requirements for public entities and another for nonpublic entities. In its update, FASB removed reference to public entities throughout and replaced it with the PBE classification (similarly changing the term “nonpublic” to an entity other than a PBE). Entities previously classified as public entities now fall under the classification of PBEs, consistent with other areas of the codification, so this change is not considered significant. However, in the “Background Information and Basis for Conclusions” discussion released with the ASU, the board noted that certain community banks could now be pulled into the PBE definition, whereas they may not have been previously categorized as a public entity for the requirements of ASC Topic 740.

Non–PBEs must also comply with increased disclosure requirements, but they vary in certain aspects from the new rules for PBEs (and rules for non–PBEs do not become effective until one year after the rules for PBEs took effect). This column focuses exclusively on the new requirements for PBEs.

Tabular rate reconciliation

In the ASU, FASB stated that, in its view, “the rate reconciliation is one of the most useful tax disclosures to provide investors with an understanding of an entity’s income taxes, including transparency into income tax risks and opportunities.” For that reason, it now requires entities to adhere to stricter disclosure requirements in terms of units of measure and categories of ETR effects in the rate reconciliations.

Units of measure: Prior to the effective date of the new disclosure requirements, public entities had the option to disclose their tabular rate reconciliation as either dollars (of income tax expense) or as a percentage (yielding ETR). In fiscal 2024, for example, Walmart Inc. presented its rate reconciliation using only the percentage method (25.5% ETR; SEC Form 10–K, Annual Report, p. 73). For the same year, Amazon.com presented its rate reconciliation using only the dollar method ($9,265 income tax expense, in millions; SEC Form 10–K, Annual Report, p. 63). And UnitedHealth Group utilized both dollars and percentages in its reconciliation ($4,829 income tax expense, in millions, and 24.1% ETR; SEC Form 10–K, Annual Report, p. 59). Going forward, under ASC Paragraph 740–10–50–12A, all PBEs are required to use both dollars and percentages in their tabular rate reconciliation, which will increase comparability between PBEs and increase decision usefulness for financial statement users.

Beginning calculation: To begin the rate reconciliation table, PBEs will first calculate an estimate of domestic federal income tax expense (benefit) by multiplying pretax income from continuing operations by the domestic statutory federal income tax rate. This approach is consistent with what companies did prior to the new requirements, but amended ASC Paragraph 740–10–50–12 clarifies that the rate used should be for the country of the domicile without adjustment for segments or subsidiaries. For an entity not domiciled in the United States, it would use the statutory federal rate in the country of domicile, and it would also disclose the alternative rate and the basis for using that rate.

Calculation of components of the rate reconciliation: The accounting steps for calculating the income tax footnote under ASC Topic 740 are generally the same as before FASB issued ASU 2023–09. However, FASB added multiple new requirements for aggregation, disaggregation, and overall disclosure of various components of the provision. Evans, “Constructing the Effective Tax Rate Reconciliation and Income Tax Provision Disclosure,” 50 The Tax Adviser 600 (August 2019),provides a comprehensive discussion and illustration for calculating multiple reconciling elements of the income tax provision under ASC Topic 740, as well as the computation of current and deferred income tax expense. This column applies these same approaches while using the newly enacted disclosure requirements for ASC Topic 740.

Categories: Previously, ASC Topic 740 did not have explicit requirements regarding the type or magnitude of items that would require separate disclosure in the rate reconciliation. Companies therefore applied SEC regulation 17 C.F.R. Section 210.4–08(h)(2), which stated no reconciling amount equating to less than 5% of income from continuing operations multiplied by the federal statutory rate needs to be disclosed. An item under this magnitude would cause a shift in ETR of less than 1.05% with the 21% federal rate for U.S.-domiciled PBEs (5% × 21% = 1.05%). Consequently, companies have been reporting line items based on size alone without any need to explicitly report any particular type of reconciling item.

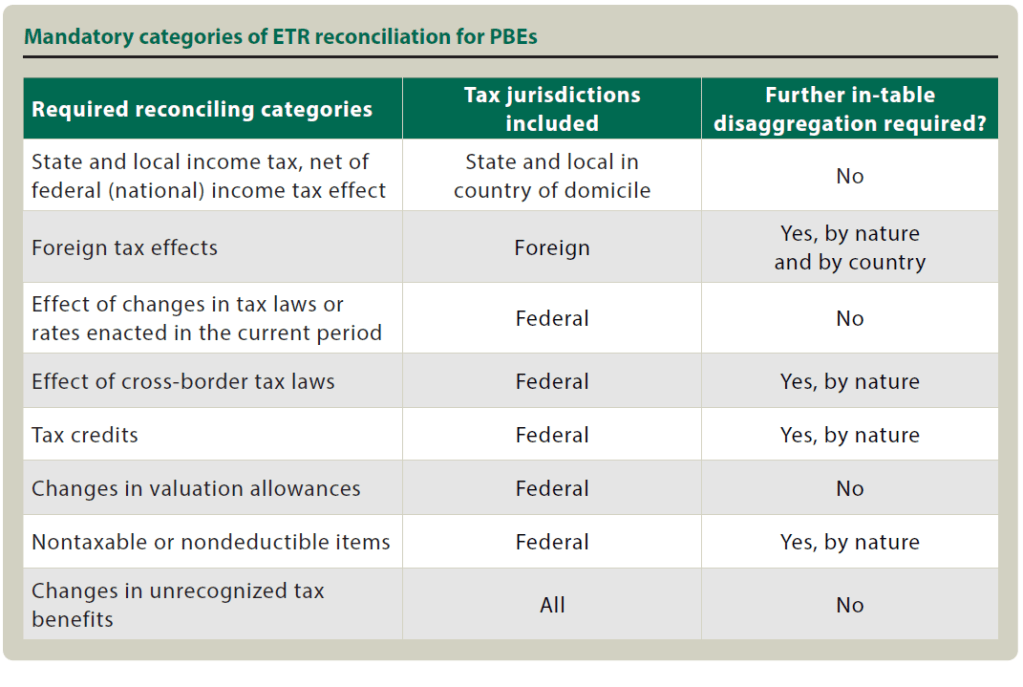

In the ASU amendments to ASC Topic 740, FASB implemented specific requirements regarding both type and magnitude of rate reconciliation line items necessitating disclosure. The table “Mandatory Categories of ETR Reconciliation for PBEs” reports the eight new categories of mandatory disclosure in the rate reconciliation table for PBEs (whether or not they meet the 5% threshold) per ASC Paragraph 740–10–50–12A. Beyond the category list in the table, the new standard also specifies that any other reconciling item reaching the 5% threshold but not already within the list of eight be separately disclosed as well.

ASC Paragraph 740–10–50–12A details which jurisdictions are included in each mandatory category, which is also reported in the table. The categories that include only the federal jurisdiction will include taxes levied by the country of domicile on earnings generated either domestically or in foreign jurisdictions. The “foreign tax effects” reconciliation category pertains to taxes imposed by foreign jurisdictions (i.e., by countries other than the country of domicile). The “effect of cross–border tax laws” category refers to additional domestic home–country federal tax consequences of foreign–source income. For a U.S. PBE, the “cross–border“category reflects the U.S. income tax laws such as GILTI (global intangible low–taxed income), BEAT (base–erosion and anti–abuse tax), and the rules for FDII (foreign–derived intangible income).

To illustrate category classification and jurisdictional differences, consider a U.S.-domiciled PBE with a tax credit. If the PBE takes advantage of a U.S. general business credit to reduce its tax liability, that effect is listed in the “tax credits” line item. Alternatively, if the entity uses a credit in a foreign jurisdiction to reduce taxes to that foreign government, that effect would be included only in the “foreign tax effects” category. If, as illustrated in ASC Paragraph 740–10–50–12A, the U.S. credit was a foreign tax credit to offset U.S. tax on foreign income, the effect would be classified in the “effects of cross–border tax laws”category. If the company uses a state credit and reduces its state income tax liability, that effect would be incorporated in the “state and local income tax” category.

Using a change to the statutory tax rate as another example, assume a rate change is enacted in the country of domicile. The effect of that adjustment would appear in the “effect of changes in tax laws or rates enacted in the current period”category. If, however, it was a foreign jurisdiction that changed its rate, the effect of remeasuring the related deferred accounts would be accounted for in the “foreign tax effects” category.

The ASU amendments to ASC Topic 740 also require additional within–category disaggregation for certain line items if individual items within that category measure at least 5% of income from continuing operations multiplied by the federal statutory rate. The table denotes which categories require this additional layer of in–table disaggregation. For reconciling items that do require it, FASB specifies the disaggregation be applied by the nature of the item, which ASC Paragraph 740–10–50–12A describes as using the “fundamental or essential characteristics” of the related event or activity. Applying the by–nature standard will require judgment as to whether certain items are similar in nature and if similar items should be combined, but PBEs are required to provide supplemental disclosure regarding their judgments where necessary for clarity per ASC Paragraph 740–10–50–12C.

In addition to the by–nature requirement, the “foreign tax effects” line item also requires PBEs to disaggregate and separately report the effect of any country that meets the 5% threshold in the rate reconciliation table. This category is the only one to have two requirements for disaggregation.

Income tax expense

ASC Paragraph 740–10–50–10B requires entities to disaggregate total income tax expense from continuing operations into its federal (domestic), state and local (domestic), and foreign components. The new standards do not require this disaggregation within the current and deferred portions, but PBEs may already have been doing so (and may continue doing so) to meet the SEC requirements of regulation 17 C.F.R. Section 210.4–08(h)(1). Regardless of the level of disaggregation of the current and deferred components, PBEs must now disclose the federal, state, and foreign components of the total provision to be in compliance with ASC Topic 740.

Select additional disclosure requirements

This summary of the fundamental changes set forth by ASU 2023–09 is not all–inclusive. There are other requirements, including for uncertain tax positions, that are not expanded upon in this column or the accompanying Excel practice set. However, this section identifies several other basic disclosure requirements.

- Pretax income from continuing operations: Per ASC Paragraph 740-10-50-10A, all entities must disaggregate and disclose pretax income or loss from continuing operations by federal (domestic) and foreign components when operating in more than one country.

- Income taxes paid: ASC Paragraph 740-10-50-22 requires PBEs to disclose income taxes paid (net of refunds) by federal, state and local, and foreign components with their Statement of Cash Flows disclosures. ASC Paragraph 740-10-50-23 further requires that if net income taxes paid to a single jurisdiction reaches at least 5% of total net income taxes paid, it must be separately disclosed.

- State and local income taxes: Though tabular disaggregation is not required in the state and local category, PBEs must qualitatively disclose the state and local jurisdictions that comprise more than 50% of the category in descending order of magnitude under ASC Paragraph 740-10-50-12B. For example, if a company operates in two states, one of which comprises 60% of the line item on the tabular reconciliation, it alone must be separately disclosed. If, however, the company operated in four states and the relative burden was 40%, 30%, 20%, and 10% of the state tax effect, the PBE would need to disclose the identity of the state that contributed 40% and 30% of the total state income tax provision (the largest contributors to reach a majority of the category total).

Application

The downloadable Excel file provides three case studies, each of which incorporates various aspects of ASC Topic 740. In order to clearly illustrate and practice the fundamental aspects of the new disclosure requirements, each case study uses the example of a domestic U.S. entity without any state or foreign tax effects. Each case study has one Excel worksheet tab showing the basic fact pattern, a tab showing the steps of working through the provision each year, and a provision tab showing the final rate reconciliation; disclosure of current, deferred, and total income tax expense; and calculation of after–tax income from continuing operations. After completing the case studies, individuals ranging from practitioners who are deepening their fundamental understanding of ASC Topic 740 to college students who are learning it for the first time will have a stronger foundation to work with the provision footnote disclosures. As PBEs issue their financial statements in compliance with these new requirements, individuals are encouraged to study the provision disclosures for a variety of companies and to compare multiple entities within the same industry or across industry categories.

Further, educators are encouraged to invite practicing ASC Topic 740 specialists into the classroom to expand upon any areas of interest within the tax provision. Practitioners could also delve deeper into more advanced areas of uncertain tax positions or multinational operations. The significant expansion of disclosure requirements shows the importance of the income tax footnote, and real–world stories and teaching from practice would yield great benefit to students who will soon enter the accounting profession.

Contributors

Allison L. Evans, CPA, Ph.D., is an associate professor of accounting at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. Annette Nellen, Esq., CPA, CGMA, is a professor in the Department of Accounting and Finance at San José State University in San José, Calif., and is a past chair of the AICPA Tax Executive Committee. For more information about this column, contact thetaxadviser@aicpa.org.